Dalai Lama is a title given by the Tibetan people to the foremost spiritual leader of the Gelug or "Yellow Hat" school of Tibetan Buddhism, the newest and most dominant of the four major schools of Tibetan Buddhism. The 14th and incumbent Dalai Lama is Tenzin Gyatso, who lives in exile as a refugee in India. The Dalai Lama is also considered to be the successor in a line of tulkus who are believed to be incarnations of Avalokiteśvara, the Bodhisattva of Compassion.

Tibet is a region in the central part of East Asia, covering much of the Tibetan Plateau and spanning about 2,500,000 km2 (970,000 sq mi). It is the homeland of the Tibetan people. Also resident on the plateau are some other ethnic groups such as the Monpa, Tamang, Qiang, Sherpa and Lhoba peoples and, since the 20th century, considerable numbers of Han Chinese and Hui settlers. Since the 1951 annexation of Tibet by the People's Republic of China, the entire plateau has been under the administration of the People's Republic of China. Tibet is divided administratively into the Tibet Autonomous Region, and parts of the Qinghai and Sichuan provinces. Tibet is also constitutionally claimed by the Republic of China as the Tibet Area since 1912.

While the Tibetan plateau has been inhabited since pre-historic times, most of Tibet's history went unrecorded until the introduction of Tibetan Buddhism around the 6th century. Tibetan texts refer to the kingdom of Zhangzhung as the precursor of later Tibetan kingdoms and the originators of the Bon religion. While mythical accounts of early rulers of the Yarlung Dynasty exist, historical accounts begin with the introduction of Buddhism from India in the 6th century and the appearance of envoys from the unified Tibetan Empire in the 7th century. Following the dissolution of the empire and a period of fragmentation in the 9th-10th centuries, a Buddhist revival in the 10th–12th centuries saw the development of three of the four major schools of Tibetan Buddhism.

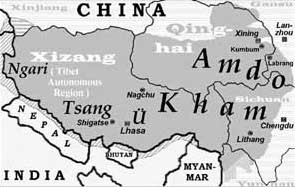

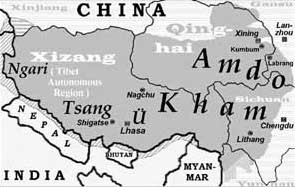

Amdo is one of the three traditional Tibetan regions, the others being U-Tsang in the west and Kham in the east. Ngari in the north-west was incorporated into Ü-Tsang. Amdo is also the birthplace of the 14th Dalai Lama. Amdo encompasses a large area from the Machu to the Drichu (Yangtze). Amdo is mostly coterminous with China's present-day Qinghai province, but also includes small portions of Sichuan and Gansu provinces.

Ü-Tsang is one of the three Tibetan regions, the others being Amdo in the north-east, and Kham in the east. Ngari in the north-west was incorporated into Ü-Tsang. Geographically Ü-Tsang covered the south-central of the Tibetan cultural area, including the Brahmaputra River watershed. The western districts surrounding and extending past Mount Kailash are included in Ngari, and much of the vast Changtang plateau to the north. The Himalayas defined Ü-Tsang's southern border. The present Tibet Autonomous Region corresponds approximately to what was ancient Ü-Tsang and western Kham.

The Tibetan sovereignty debate refers to two political debates. The first political debate is about whether or not the various territories which are within the People's Republic of China (PRC) that are claimed as political Tibet should separate themselves from China and become a new sovereign state. Many of the points in this political debate rest on the points which are within the second historical debate, about whether Tibet was independent or subordinate to China during certain periods of its recent history.

Tibet came under the control of People's Republic of China (PRC) after the Government of Tibet signed the Seventeen Point Agreement which the 14th Dalai Lama ratified on 24 October 1951, but later repudiated on the grounds that he rendered his approval for the agreement while under duress. This occurred after attempts by the Tibetan Government to gain international recognition, efforts to modernize its military, negotiations between the Government of Tibet and the PRC, and a military conflict in the Chamdo area of western Kham in October 1950. The series of events came to be called the "Peaceful Liberation of Tibet" by the Chinese government, and the "Chinese invasion of Tibet" by the Central Tibetan Administration and the Tibetan diaspora.

The Golden Urn refers to a method for selecting Tibetan reincarnations by drawing lots or tally sticks from a Golden Urn introduced by the Qing dynasty of China in 1793. After the Sino-Nepalese War, the Qianlong Emperor promulgated the 29-Article Ordinance for the More Effective Governing of Tibet, which included regulations on the selection of lamas. The Golden Urn was introduced ostensibly to prevent cheating and corruption in the selection process but also to position the Qianlong Emperor as a religious authority capable of adducing incarnation candidates. A number of lamas, such as the 8th and 9th Panchen Lamas and the 10th Dalai Lama, were confirmed using the Golden Urn. In cases where the Golden Urn was not used, the amban was consulted. Usage of the Golden Urn ended with the fall of the Qing dynasty in 1911.

Elliot Sperling was one of the world's leading historians of Tibet and Tibetan-Chinese relations, and a MacArthur Fellow. He spent most of his scholarly career as an associate professor at Indiana University's Department of Central Eurasian Studies, with seven years as the department's chair.

The Ming dynasty considered Tibet to be part of Western Regions or "foreign barbarians". The exact nature of their relations is under dispute by modern scholars. Analysis of the relationship is further complicated by modern political conflicts and the application of Westphalian sovereignty to a time when the concept did not exist. The Historical Status of China's Tibet, a book published by the People's Republic of China, asserts that the Ming dynasty had unquestioned sovereignty over Tibet by pointing to the Ming court's issuing of various titles to Tibetan leaders, Tibetans' full acceptance of the titles, and a renewal process for successors of these titles that involved traveling to the Ming capital. Scholars in China also argue that Tibet has been an integral part of China since the 13th century and so it was a part of the Ming Empire. However, most scholars outside China, such as Turrell V. Wylie, Melvin C. Goldstein, and Helmut Hoffman, say that the relationship was one of suzerainty, Ming titles were only nominal, Tibet remained an independent region outside Ming control, and it simply paid tribute until the Jiajing Emperor, who ceased relations with Tibet.

The Phagmodrupa dynasty or Pagmodru was a dynastic regime that held sway over Tibet or parts thereof from 1354 to the early 17th century. It was established by Tai Situ Changchub Gyaltsen of the Lang family at the end of the Yuan dynasty. The dynasty had a lasting importance on the history of Tibet; it created an autonomous kingdom after Yuan rule, revitalized the national culture, and brought about a new legislation that survived until the 1950s. Nevertheless, the Phagmodrupa had a turbulent history due to internal family feuding and the strong localism among noble lineages and fiefs. Its power receded after 1435 and was reduced to Ü in the 16th century due to the rise of the ministerial family of the Rinpungpa. It was defeated by the rival Tsangpa dynasty in 1613 and 1620, and was formally superseded by the Ganden Phodrang regime founded by the 5th Dalai Lama in 1642. In that year, Güshi Khan of the Khoshut formally transferred the old possessions of Sakya, Rinpung and Phagmodrupa to the "Great Fifth".

Tibet was a de facto independent state in East Asia that lasted from the collapse of the Manchu-led Qing dynasty in 1912 until its annexation by the People's Republic of China in 1951.

The Upper Mongols, also known as the Köke Nuur Mongols or Qinghai Mongols, are ethnic Mongol people of Oirat and Khalkha origin who settled around Qinghai Lake in so-called Upper Mongolia. As part of the Khoshut Khanate of Tsaidam and the Koke Nuur, they played a major role in Sino–Mongol–Tibetan politics during the 17th and 18th centuries. The Upper Mongols adopted Tibetan dress and jewelry despite still living in the traditional Mongolian ger and writing in the script.

There were several Mongol invasions of Tibet. The earliest is the alleged plot to invade Tibet by Genghis Khan in 1206, which is considered anachronistic; there is no evidence of Mongol-Tibetan encounters prior to the military campaign in 1240. The first confirmed campaign is the invasion of Tibet by the Mongol general Doorda Darkhan in 1240, a campaign of 30,000 troops that resulted in 500 casualties. The campaign was smaller than the full-scale invasions used by the Mongols against large empires. The purpose of this attack is unclear, and is still in debate among Tibetologists. Then in the late 1240s Mongol prince Godan invited Sakya lama Sakya Pandita, who urged other leading Tibetan figures to submit to Mongol authority. This is generally considered to have marked the beginning of Mongol rule over Tibet, as well as the establishment of patron and priest relationship between Mongols and Tibetans. These relations were continued by Kublai Khan, who founded the Mongol Yuan dynasty and granted authority over whole Tibet to Drogon Chogyal Phagpa, nephew of Sakya Pandita. The Sakya-Mongol administrative system and Yuan administrative rule over the region lasted until the mid-14th century, when the Yuan dynasty began to crumble.

Tibet under Yuan rule refers to the Mongol-led Yuan dynasty's rule over Tibet from 1244 to 1354. During the Yuan dynasty rule of Tibet, the region was structurally, militarily and administratively controlled by the Mongol-led Yuan dynasty of China. In the history of Tibet, Mongol rule was established after Sakya Pandita got power in Tibet from the Mongols in 1244, following the 1240 Mongol conquest of Tibet led by the Mongol general with the title doord darkhan. It is also called the Sakya dynasty after the favored Sakya school of Tibetan Buddhism.

The Tibet Improvement Party was a nationalist, revolutionary, anti-feudal and pro-Republic of China political party in Tibet. It was affiliated with the Kuomintang and was supported by mostly Khampas, with the Pandatsang family playing a key role.

The 1910 Chinese expedition to Tibet or the Chinese invasion of Tibet in 1910 was a military campaign of the Qing dynasty to establish direct rule in Tibet in early 1910. The expedition occupied Lhasa on February 12 and officially deposed the 13th Dalai Lama on the 25th.

Buddhists, predominantly from India, first actively disseminated their practices in Tibet from the 6th to the 9th centuries CE. During the Era of Fragmentation, Buddhism waned in Tibet, only to rise again in the 11th century. With the Mongol invasion of Tibet and the establishment of the Mongol Yuan dynasty (1271–1368) in China, Tibetan Buddhism spread beyond Tibet to Mongolia and China. From the 14th to the 20th centuries, Tibetan Buddhism was patronized by the Chinese Ming dynasty (1368–1644) and the Manchurian Qing dynasty (1644–1912) which ruled China.

The Ganden Phodrang or Ganden Podrang was the Tibetan system of government established by the 5th Dalai Lama in 1642, after the Oirat lord Güshi Khan who founded the Khoshut Khanate conferred all temporal power on the 5th Dalai Lama in a ceremony in Shigatse in the same year. Lhasa again became the capital of Tibet, and the Ganden Phodrang operated until the 1950s. The Ganden Phodrang accepted China's Qing emperors as overlords after the 1720 expedition, and the Qing became increasingly active in governing Tibet starting in the early 18th century. After the fall of the Qing empire in 1912, the Ganden Phodrang government lasted until the 1950s, when Tibet was annexed by the People's Republic of China. During most of the time from the early Qing period until the end of Ganden Phodrang rule, a governing council known as the Kashag operated as the highest authority in the Ganden Phodrang administration.

Tibet under Qing rule refers to the Qing dynasty's rule over Tibet from 1720 to 1912. The Qing rulers incorporated Tibet into the empire along with other Inner Asia territories, although the actual extent of the Qing dynasty's control over Tibet during this period has been the subject of political debate. The Qing called Tibet a fanbu, fanbang or fanshu, which has usually been translated as "vassal", "vassal state", or "borderlands", along with areas like Xinjiang and Mongolia. Like the preceding Yuan dynasty, the Manchus of the Qing dynasty exerted military and administrative control over Tibet while granting it a degree of political autonomy.