Evidence of modern human presence in the northern and central highlands of Indochina, which constitute the territories of the modern Laotian nation-state, dates back to the Lower Paleolithic. These earliest human migrants are Australo-Melanesians—associated with the Hoabinhian culture—and have populated the highlands and the interior, less accessible regions of Laos and all of Southeast Asia to this day. The subsequent Austroasiatic and Austronesian marine migration waves affected landlocked Laos only marginally, and direct Chinese and Indian cultural contact had a greater impact on the country.

The Lao people are a Tai ethnic group native to Southeast Asia. They primarily speak the Lao language, which belongs to the Kra–Dai language family. Lao people constitute the majority ethnic group of Laos, comprising 53.2% of the country's total population. They are also found in significant numbers in northeastern Thailand, particularly in the Isan region, as well as in smaller communities in Cambodia, Vietnam, and Myanmar.

Lan Xang or Lancang was a Lao kingdom that held the area of present-day Laos from 1353 to 1707. For three and a half centuries, Lan Xang was one of the largest kingdoms in Southeast Asia. The kingdom is the basis for Laos's national historic and cultural identity.

Luang Phabang, or Louangphabang, commonly transliterated into Western languages from the pre-1975 Lao spelling ຫຼວງພຣະບາງ as Luang Prabang, literally meaning "Royal Buddha Image", is a city in north central Laos, consisting of 58 adjacent villages, of which 33 comprise the UNESCO Town of Luang Prabang World Heritage Site. It was listed in 1995 for unique and remarkably well preserved architectural, religious and cultural heritage, a blend of the rural and urban developments over several centuries, including the French colonial influences during the 19th and 20th centuries.

Setthathirath or Xaysettha is considered one of the great leaders in Lao history. Throughout the 1560s until his death, he successfully defended his kingdom of Lan Xang against military campaigns of Burmese conqueror Bayinnaung, who had already subdued Xieng Mai in 1558 and Ayutthaya in 1564. Setthathirath was a prolific builder and erected many Buddhist monuments including Wat Xieng Thong in Luang Prabang, Haw Phra Kaew, Wat Ong Teu Mahawihan and the Pha That Luang in Vientiane.

Pakse is the capital and most populous city of the southern Laotian province of Champasak. Located at the confluence of the Xe Don and Mekong Rivers, the district had a population of approximately 77,900 at the 2015 Laotian census. Pakse was the capital of the Kingdom of Champasak until it was unified with the rest of Laos in 1946.

Nong Khai is a city in northeast Thailand. It is the capital of Nong Khai province. Nong Khai city is located in Mueang Nong Khai district.

Laos developed its culture and customs as the inland crossroads of trade and migration in Southeast Asia over millennia. As of 2012 Laos has a population of roughly 6.4 million spread over 236,800 km2, yielding one of the lowest population densities in Asia. Yet the country of Laos has an official count of over forty-seven ethnicities divided into 149 sub-groups and 80 different languages. The Lao Loum have throughout the country's history comprised the ethnic and linguistic majority. In Southeast Asia, traditional Lao culture is considered one of the Indic cultures.

'Phra Lak Phra Ram' is the national epic of the Lao people, an adaptation of the ancient Indian epic Ramayana.

Haw Phra Kaew, also written as Ho Prakeo, Hor Pha Keo, HoPhraKaew, Ho Phra Kaeo and other similar spellings, is a former temple in Vientiane, Laos. It is situated on Setthathirath Road, to the southeast of Wat Si Saket. It was first built in 1565 to house the Emerald Buddha, but has been rebuilt several times. The interior now houses a museum of religious art and a small shop.

Wat Phra That Phanom is a Buddhist temple in the That Phanom District in the south of Nakhon Phanom Province, all within the Isan region of Thailand near the Lao border. According to local legend, the temple contains in the pagoda the Phra Uranghathat (พระอุรังคธาตุ)/Phra Ura (พระอุระ)/Buddha's breast bones. As such, it is one of the most important structures for Theravada Buddhists and the most important Buddhist site in the province, with an annual week-long festival being held in the town of That Phanom to honour the temple. These festival attract thousands of people who make pilgrimages to the shrine. In Thai folk Buddhism, Wat Phra That Phanom is a popular pilgrimage destination for those born in the year of the Monkey.

Theravada Buddhism is the largest and dominant religion in Laos. Theravada Buddhism is central to Lao cultural identity. The national symbol of Laos is the That Luang stupa, a stupa with a pyramidal base capped by the representation of a closed lotus blossom which was built to protect relics of the Buddha. It is practiced by 66% of the population. Almost all ethnic or "lowland" Lao people are followers of Theravada Buddhism; however, they constitute more than 50% of the population. The remainder of the population belongs to at least 48 distinct ethnic minority groups. Most of these ethnic groups are practitioners of Tai folk religions, with beliefs that vary greatly among groups.

A wat is a type of Buddhist and Hindu temple in Cambodia, Laos, East Shan State, Yunnan, the Southern Province of Sri Lanka, and Thailand.

Vientiane province is a province of Laos in the country's northwest. As of 2015 the province had a population of 419,090. Vientiane province covers an area of 15,610 square kilometres (6,030 sq mi) composed of 11 districts. The principal towns are Vang Vieng and Muang Phôn-Hông.

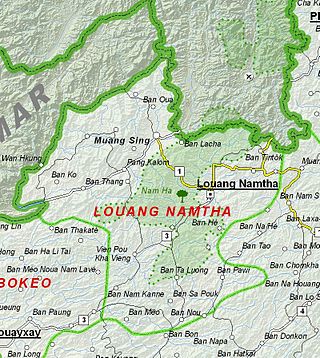

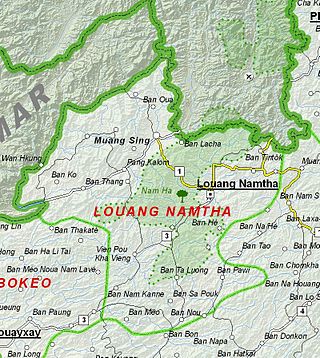

Luang Namtha is a province of Laos in the country's north. From 1966 to 1976 it formed, together with Bokeo, the province of Houakhong. Luang Namtha province covers an area of 9,325 square kilometres (3,600 sq mi). Its provincial capital is Luang Namtha. The province borders Yunnan, China to the north, Oudomxai province to the east and southeast, Bokeo province to the southwest, and Shan State, Myanmar to the northwest.

Vientiane Prefecture is a prefecture of Laos, in northwest Laos. The national capital, Vientiane, is in the prefecture. The prefecture was created in 1989, when it was split off from Vientiane province.

Luang Prabang is a province in northern Laos. Its capital of the same name, Luang Prabang, was the capital of the Lan Xang Kingdom during the 13th to 16th centuries. It is listed since 1995 by UNESCO as a World Heritage Site for unique architectural, religious and cultural heritage, a blend of the rural and urban developments over several centuries, including the French colonial influences during the 19th and 20th centuries. The province has 12 districts. The Royal Palace, the national museum in the capital city, and the Phou Loei Protected Reserve are important sites. Notable temples in the province are the Wat Xieng Thong, Wat Wisunarat, Wat Sen, Wat Xieng Muan, and Wat Manorom. The Lao New Year is celebrated in April as The Bun Pi Mai.

Champasak is a province in southwestern Laos, near the borders with Thailand and Cambodia. It is one of the three principalities that succeeded the Lao kingdom of Lan Xang. As of the 2015 census, it had a population of 694,023. The capital is Pakse, but the province takes its name from Champasak, the former capital of the Kingdom of Champasak.

The people of Laos have a rich literary tradition dating back at least six hundred years, with the oral and storytelling traditions of its peoples dating back much earlier. Lao literature refers to the written productions of Laotian peoples, its émigrés, and to Lao-language works. In Laos today there are over forty-seven recognized ethnic groups, with the Lao Loum comprising the majority group. Lao is officially recognized as the national language, but owing to the ethnic diversity of the country the literature of Laos can generally be grouped according to four ethnolinguistic families: Lao-Tai (Tai-Kadai); Mon-Khmer (Austroasiatic); Hmong-Mien (Miao-Yao), and Sino-Tibetan. As an inland crossroads of Southeast Asia the political history of Laos has been complicated by frequent warfare and colonial conquests by European and regional rivals.