| |

| Data | |

|---|---|

| Access to an at least basic water source | 97% (2015) [1] |

| Access to at least basic sanitation | 86% (2015) [1] |

| Share of collected wastewater treated | 35% (2000) [2] |

| Average urban water use (L/person/day) | 143 |

| Average urban water and sanitation tariff (US$/m3) | 0.82 (2006) [3] |

| Share of household metering | 76% [4] |

| Annual investment in WSS | US$3.4 bn corresponding to US$17/capita (2012) |

| Financing | 51% self-financing by utilities (2004) |

| Institutions | |

| Decentralization to municipalities | Substantial |

| National water and sanitation company | None |

| Water and sanitation regulator | State-level multi-sector |

| Responsibility for policy setting | Ministry of Cities |

| No. of urban service providers | 26 State Companies, >1500 municipalities for water, >4500 municipalities for sanitation |

Access to at least basic water increased from 94% to 97% between 2000 and 2015; an increase in access to at least basic sanitation from 73% to 86% in the same period. [5]

Contents

- Access

- Water use

- Reaching the poor

- History and recent developments

- Municipal service provision (prior to 1968)

- The National Water Supply and Sanitation Plan PLANASA (1968–1986)

- Gradual municipalization, some private sector participation (1986–2002)

- The Lula administration (2003–2011)

- National Sanitation Plan

- Infrastructure

- Responsibility for water supply and sanitation

- Policy and regulation

- Service provision

- Utility associations

- Efficiency

- Financial aspects

- Tariffs

- Revenue collection

- Investment

- Financing

- External cooperation

- Inter-American Development Bank

- World Bank

- Japan

- Germany

- See also

- References

- External links

- English

- Portuguese

Brazil has a national system to finance water and sanitation infrastructure; a high level of cost recovery compared to most other developing countries.

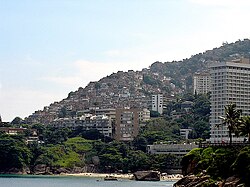

A high number of poor Brazilians live in urban slums (favela) and in rural areas without access to piped water or sanitation. Water is scarce in the northeast of Brazil. Water pollution is common, especially in the southeast of the country. Brazil has a low share of collected wastewater that is being treated (35% in 2000), and long-standing tensions between the federal, state and municipal governments about their respective roles in the sector.