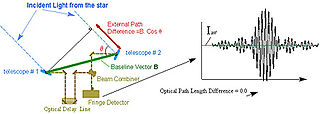

Astrometry is a branch of astronomy that involves precise measurements of the positions and movements of stars and other celestial bodies. It provides the kinematics and physical origin of the Solar System and this galaxy, the Milky Way.

Abbé Nicolas-Louis de Lacaille, formerly sometimes spelled de la Caille, was a French astronomer and geodesist who named 14 out of the 88 constellations. From 1750 to 1754, he studied the sky at the Cape of Good Hope in present-day South Africa. Lacaille observed over 10,000 stars using just a half-inch refracting telescope.

Edward James Stone FRS FRAS was an English astronomer.

The Carte du Ciel and the Astrographic Catalogue were two distinct but connected components of a massive international astronomical project, initiated in the late 19th century, to catalogue and map the positions of millions of stars as faint as 11th or 12th magnitude. Twenty observatories from around the world participated in exposing and measuring more than 22,000 (glass) photographic plates in an enormous observing programme extending over several decades. Despite, or because of, its vast scale, the project was only ever partially successful – the Carte du Ciel component was never completed, and for almost half a century the Astrographic Catalogue part was largely ignored. However, the appearance of the Hipparcos Catalogue in 1997 has led to an important development in the use of this historical plate material.

Thomas Henderson FRSE FRS FRAS was a Scottish astronomer and mathematician noted for being the first person to measure the distance to Alpha Centauri, the major component of the nearest stellar system to Earth, the first to determine the parallax of a fixed star, and for being the first Astronomer Royal for Scotland.

Sir David Gill was a Scottish astronomer who is known for measuring astronomical distances, for astrophotography and geodesy. He spent much of his career in South Africa.

Robert Thorburn Ayton Innes FRSE FRAS was a British-born South African astronomer best known for discovering Proxima Centauri in 1915, and numerous binary stars. He was also the first astronomer to have seen the Great January Comet of 1910, on 12 January. He was the founding director of a meteorological observatory in Johannesburg, which was later converted to an astronomical observatory and renamed to Union Observatory. He was the first Union Astronomer. Innes House, designed by Herbert Baker, built as his residence at the observatory, today houses the South African Institute of Electrical Engineers.

William Henry Finlay (FRAS) was a South African astronomer. He was First Assistant at the Cape Observatory from 1873 to 1898 under Edward James Stone. He discovered the periodic comet 15P/Finlay. Earlier, he was one of the first to spot the "Great Comet of 1882". The first telegraphic determinations of longitude along the western coast of Africa were made by Finlay and T. F. Pullen.

Union Observatory also known as Johannesburg Observatory (078) is a defunct astronomical observatory in Johannesburg, South Africa that was operated between 1903 and 1971. It is located on Observatory Ridge, the city's highest point at 1,808 metres altitude in the suburb Observatory.

South African Astronomical Observatory (SAAO) is the national centre for optical and infrared astronomy in South Africa. It was established in 1972. The observatory is run by the National Research Foundation of South Africa. The facility's function is to conduct research in astronomy and astrophysics. The primary telescopes are located in Sutherland, which is 370 kilometres (230 mi) from Observatory, Cape Town, where the headquarters is located.

Sir Thomas Maclear was an Irish-born South African astronomer who became Her Majesty's astronomer at the Cape of Good Hope.

James Dunlop FRSE was a Scottish astronomer, noted for his work in Australia. He was employed by Sir Thomas Brisbane to work as astronomer's assistant at his private observatory, once located at Paramatta, New South Wales, about 23 kilometres (14 mi) west of Sydney during the 1820s and 1830s. Dunlop was mostly a visual observer, doing stellar astrometry work for Brisbane, and after its completion, then independently discovered and catalogued many new telescopic southern double stars and deep-sky objects. He later became the Superintendent of Paramatta Observatory when it was finally sold to the New South Wales Government.

Grubb Parsons was a historic manufacturer of telescopes, active in the 19th and 20th centuries. They built numerous large research telescopes, including several that were the largest in the world of their type.

John Jackson was a Scottish astronomer.

David Stanley Evans was a British astronomer, noted for his use of lunar occultations to measure stellar angular diameters during the 1950s.

The Great Melbourne Telescope was built by the Grubb Telescope Company in Dublin, Ireland in 1868, and installed at the Melbourne Observatory in Melbourne, Australia in 1869. In 1945 that Observatory closed and the telescope was sold and moved to the Mount Stromlo Observatory near Canberra. It was rebuilt in the late 1950s. In 2003 the telescope, still in use as an observatory, was severely damaged in a bushfire. About 70% of the components were salvageable; a project to restore the telescope to working condition started in 2013.

Ian Stewart Glass is an infrared astronomer and scientific historian living in Cape Town, South Africa.

Potsdam Great Refractor is an historic astronomical telescope in an observatory in Potsdam, Germany.

The Yapp telescope is a 36-inch reflecting telescope of the United Kingdom, now located at the Observatory Science Centre at Herstmonceux.

Brian Warner was a British South African optical astronomer who was Emeritus Distinguished Professor of natural philosophy at the University of Cape Town. Warner's research included cataclysmic variable stars, pulsars, degenerate stars and binary stars. He also researched and published on the history of astronomy in South Africa.