Last Island

Many Last Island vacationers hoping to escape the approaching storm were awaiting the scheduled arrival of the ship Star, which provided regular service to the mainland. However, the Star was blown off course, barely escaping sailing into the open gulf, directly into the hurricane, where it would have almost certainly been lost. Passenger Tom Ellis, an experienced captain in local waters, and a few other passengers observed the ship was off course. Ellis alerted Captain Abe Smith, who corrected the course and barely making headway against the winds, managed to pull into the channel behind the hotel. The Star was swept, crashing into shore and beached on the sand, where it stayed through the storm. [6]

Visibility during the storm was extremely limited and eyes were blasted by sand until water covered the beaches. Sometime between 4:00 and 5:00 PM, the storm surge occurred suddenly, with the water rising several feet in a matter of minutes. The storm surge submerged the entire island and destroyed all of the buildings. The hotel, which held many women and children on the second floor and men on the first, collapsed, crushing many and sweeping others out to sea. [6]

Several survivors managed to make their way to the hull of the Star. By tying himself with a rope to the Star, Captain Abe Smith was able to rescue at least 40 people from the storm surge. [6] The Star would serve as a shelter for the survivors until rescuers arrived three days later.

Many managed to survive by sheltering in or behind overturned cisterns, which were large wooden cylindrical tanks reinforced with iron hoops. Some clung to the raised foundations of the cisterns and a few to trees. A dozen people survived by clinging to a large piece of rotating playground equipment atop a levee. [7] Many people floated on debris, including wall sections, logs and furniture. A sturdy wooden enclosure that held large terrapins, a regional delicacy, provided enough protection to save several individuals. Another group survived by burying their feet in the sand and holding hands. Some survivors were carried to the marshes on the mainland, although some perished from injuries or lack of food and water. [6]

Of the approximately 400 vacationers on the island, 198 were known or presumed dead and 203 were known survivors. Dixon (2009) provides lists of survivors and the dead. [6]

Several of the victims were enslaved people. Some of the enslaved people were credited with rescuing others, including several children.

The tragedy had a major impact on the planter society, which lost many members. At the time of the hurricane approximately two-thirds of the millionaires in the U.S. lived in Louisiana, many of those being plantation owners, especially sugar growers. Of the social group affected, many were friends, acquaintances, or related by marriage or known through business.

The family home of three of the Last Island casualties was Shadows-on-the-Teche in New Iberia, Louisiana, now a National Historic Landmark. Mrs. Frances Weeks (Magill) Pruett and her children Mary Ida Magill and Augustine Magill died in the natural disaster. The two children were buried in the plantation's cemetery.

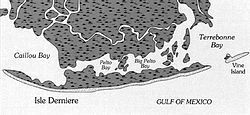

The island itself was split into the Last Islands (Isles Dernieres). [8] The island reportedly stayed submerged for several days before parts of it re-emerged as large sandbars. After the storm surge, the remains of the Star were the only sign that an island had ever existed there. [8] Presently, the area is the Isles Dernieres Barrier Islands Refuge owned and managed by the Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries to provide protected nesting grounds for pelicans and other waterbirds. [9]

Elsewhere

The following are the numbers of deaths offshore: [6]

- Steamer Nautilus: 85

- Steamer Manilla: 13

- Schooner Ellen: 15

- Other losses at sea: 20

On Calliou Island, which was located near Last Island, four homes were destroyed, and the others suffered substantial damage. Tides generated by the storm capsized two boats and swept away stock. [10] The city of New Orleans was inundated with 13.14 inches (334 mm) of rain. Every building in Abbeville was destroyed, including St. Mary Magdalen Church. Crops along the Mermentau River suffered large losses from freshwater flooding. Farther east, storm surge and abnormally high tides left some sections of Plaquemines Parish inundated by several feet of water, resulting in a near-total loss of rice crops. Severe losses to orange crops were reported in the area. [8] Extensive damage occurred in St. Tammany Parish at Lewisburg, Mandeville, and other areas near the Tchefuncte River. The storm swept away bathhouses and wharves, while also downing fences, trees, and vegetation. [11]