Archaeoastronomy is the interdisciplinary or multidisciplinary study of how people in the past "have understood the phenomena in the sky, how they used these phenomena and what role the sky played in their cultures". Clive Ruggles argues it is misleading to consider archaeoastronomy to be the study of ancient astronomy, as modern astronomy is a scientific discipline, while archaeoastronomy considers symbolically rich cultural interpretations of phenomena in the sky by other cultures. It is often twinned with ethnoastronomy, the anthropological study of skywatching in contemporary societies. Archaeoastronomy is also closely associated with historical astronomy, the use of historical records of heavenly events to answer astronomical problems and the history of astronomy, which uses written records to evaluate past astronomical practice.

A lunar phase or Moon phase is the apparent shape of the Moon's directly sunlit portion as viewed from the Earth. Because the Moon is tidally locked with the Earth, the same hemisphere is always facing the Earth. In common usage, the four major phases are the new moon, the first quarter, the full moon and the last quarter; the four minor phases are waxing crescent, waxing gibbous, waning gibbous, and waning crescent. A lunar month is the time between successive recurrences of the same phase: due to the eccentricity of the Moon's orbit, this duration is not perfectly constant but averages about 29.5 days.

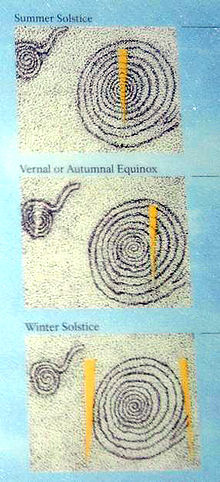

A solstice is the time when the Sun reaches its most northerly or southerly excursion relative to the celestial equator on the celestial sphere. Two solstices occur annually, around 20–22 June and 20–22 December. In many countries, the seasons of the year are defined by reference to the solstices and the equinoxes.

Chaco Culture National Historical Park is a United States National Historical Park in the American Southwest hosting a concentration of pueblos. The park is located in northwestern New Mexico, between Albuquerque and Farmington, in a remote canyon cut by the Chaco Wash. Containing the most sweeping collection of ancient ruins north of Mexico, the park preserves one of the most important pre-Columbian cultural and historical areas in the United States.

The September equinox is the moment when the Sun appears to cross the celestial equator, heading southward. Because of differences between the calendar year and the tropical year, the September equinox may occur from September 21 to 24.

The March equinox or northward equinox is the equinox on the Earth when the subsolar point appears to leave the Southern Hemisphere and cross the celestial equator, heading northward as seen from Earth. The March equinox is known as the vernal equinox in the Northern Hemisphere and as the autumnal equinox in the Southern Hemisphere.

The prehistoric monument of Stonehenge has long been studied for its possible connections with ancient astronomy. The site is aligned in the direction of the sunrise of the summer solstice and the sunset of the winter solstice.

Pueblo Bonito is the largest and best-known great house in Chaco Culture National Historical Park, northern New Mexico. It was built by the Ancestral Puebloans who occupied the structure between AD 828 and 1126.

A lunar standstill or lunistice is when the Moon reaches its furthest north or furthest south point during the course of a month. The declination at lunar standstill varies in a cycle 18.6 years long between 18.134° and 28.725°, due to lunar precession. These extremes are called the minor and major lunar standstills.

Una Vida is an archaeological site located in Chaco Canyon, San Juan County, New Mexico, United States. According to tree rings surrounding the site, its construction began around 800 AD, at the same time as Pueblo Bonito, and it is one of the three earliest Chacoan Ancestral Puebloan great houses. Comprising at least two stories and 160 rooms, it shares an arc or D-shaped design with its contemporaries, Peñasco Blanco and Pueblo Bonito, but has a unique "dog leg" addition made necessary by topography. It is located in one of the canyon's major side drainages, near Gallo Wash, and was massively expanded after 930 AD.

Carahunge, also known as Zorats Karer, Dik-Dik Karer, Tsits Karer and Karenish (Քարենիշ), is a prehistoric archaeological site near the town of Sisian in the Syunik Province of Armenia. It is also often referred to among international tourists as the "Armenian Stonehenge".

The summer solstice or estival solstice occurs when one of Earth's poles has its maximum tilt toward the Sun. It happens twice yearly, once in each hemisphere. The summer solstice is the day with the longest period of daylight and shortest night of the year in that hemisphere, when the sun is at its highest position in the sky. At either pole there is continuous daylight at the time of its summer solstice. The opposite event is the winter solstice.

Maya astronomy is the study of the Moon, planets, Milky Way, Sun, and astronomical phenomena by the Precolumbian Maya civilization of Mesoamerica. The Classic Maya in particular developed some of the most accurate pre-telescope astronomy in the world, aided by their fully developed writing system and their positional numeral system, both of which are fully indigenous to Mesoamerica. The Classic Maya understood many astronomical phenomena: for example, their estimate of the length of the synodic month was more accurate than Ptolemy's, and their calculation of the length of the tropical solar year was more accurate than that of the Spanish when the latter first arrived. Many temples from the Maya architecture have features oriented to celestial events.

The Ancestral Puebloans, also known as the Anasazi and by the earlier term the Basketmaker-Pueblo culture, were an ancient Native American culture that spanned the present-day Four Corners region of the United States, comprising southeastern Utah, northeastern Arizona, northwestern New Mexico, and southwestern Colorado. They are believed to have developed, at least in part, from the Oshara tradition, which developed from the Picosa culture. The people and their archaeological culture are often referred to as Anasazi, a term introduced by Alfred V. Kidder from the Navajo word anaasází meaning 'enemy ancestors' although Kidder thought it meant 'old people'. Contemporary Puebloans object to the use of this term, with some viewing it as derogatory.

Gallo Cliff Dwelling is a pair of Ancestral Puebloan room blocks that lie under a cliff in Gallo Canyon, New Mexico, United States. Located adjacent to the National Park Service campground, the site includes a central room that features a multi-storied wall and a five-room structure with kiva that was probably occupied during the early 12th century by Mesa Veredans, who built in a distinctive McElmo masonry style. The inhabitants of these dwellings dates from 1150 to 1200 AD, or the late Chacoan Period. National Park Service excavations there during the 1960s uncovered a quantity of perishable items, including sandals and baskets, from the rooms.

Anna Sofaer is an American researcher and educator on the archaeoastronomy of the Ancestral Puebloans of the American Southwest and other ancient cultures. In 1977, she "rediscovered" the astronomical marker site known as the Sun Dagger on Fajada Butte in Chaco Culture National Historical Park. Research has indicated this site records the solar and lunar cycles.

The Sun Circle is a sculpture located within the Rillito River Park, a Pima County linear park running along the banks of the Rillito River north of Tucson, Arizona. Inspired by the archaeoastronomy of the southwestern United States Ancestral Puebloans in locations such as Chaco Canyon, Sun Circle uses astronomical alignments to cast shadows and light through apertures (windows) to align with corresponding windows on equinoxes and solstices at sunrise and sunset.

This article describes the astronomy of the Muisca. The Muisca, one of the four advanced civilisations in the Americas before the Spanish conquest of the Muisca, had a thorough understanding of astronomy, as evidenced by their architecture and calendar, important in their agriculture.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to the planet Earth: