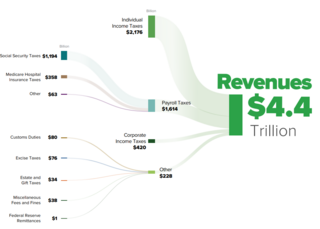

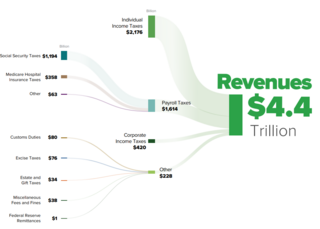

The United States has separate federal, state, and local governments with taxes imposed at each of these levels. Taxes are levied on income, payroll, property, sales, capital gains, dividends, imports, estates and gifts, as well as various fees. In 2020, taxes collected by federal, state, and local governments amounted to 25.5% of GDP, below the OECD average of 33.5% of GDP.

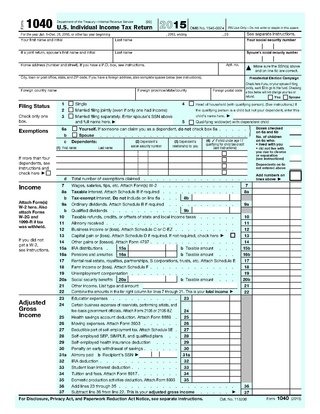

An income tax is a tax imposed on individuals or entities (taxpayers) in respect of the income or profits earned by them. Income tax generally is computed as the product of a tax rate times the taxable income. Taxation rates may vary by type or characteristics of the taxpayer and the type of income.

A dividend tax is a tax imposed by a jurisdiction on dividends paid by a corporation to its shareholders (stockholders). The primary tax liability is that of the shareholder, though a tax obligation may also be imposed on the corporation in the form of a withholding tax. In some cases the withholding tax may be the extent of the tax liability in relation to the dividend. A dividend tax is in addition to any tax imposed directly on the corporation on its profits. Some jurisdictions do not tax dividends.

An expense is an item requiring an outflow of money, or any form of fortune in general, to another person or group as payment for an item, service, or other category of costs. For a tenant, rent is an expense. For students or parents, tuition is an expense. Buying food, clothing, furniture, or an automobile is often referred to as an expense. An expense is a cost that is "paid" or "remitted", usually in exchange for something of value. Something that seems to cost a great deal is "expensive". Something that seems to cost little is "inexpensive". "Expenses of the table" are expenses for dining, refreshments, a feast, etc.

A limited liability company (LLC) is the United States-specific form of a private limited company. It is a business structure that can combine the pass-through taxation of a partnership or sole proprietorship with the limited liability of a corporation. An LLC is not a corporation under the laws of every state; it is a legal form of a company that provides limited liability to its owners in many jurisdictions. LLCs are well known for the flexibility that they provide to business owners; depending on the situation, an LLC may elect to use corporate tax rules instead of being treated as a partnership, and, under certain circumstances, LLCs may be organized as not-for-profit. In certain U.S. states, businesses that provide professional services requiring a state professional license, such as legal or medical services, may not be allowed to form an LLC but may be required to form a similar entity called a professional limited liability company (PLLC).

A tax deduction or benefit is an amount deducted from taxable income, usually based on expenses such as those incurred to produce additional income. Tax deductions are a form of tax incentives, along with exemptions and tax credits. The difference between deductions, exemptions, and credits is that deductions and exemptions both reduce taxable income, while credits reduce tax.

Negative gearing is a form of financial leverage whereby an investor borrows money to acquire an income-producing investment and the gross income generated by the investment is less than the cost of owning and managing the investment, including depreciation and interest charged on the loan. The investor may enter into a negatively geared investment expecting tax benefits or the capital gain on the investment after it is sold to exceed the accumulated losses of holding the investment. The investor would take into account the tax treatment of negative gearing, which may generate additional benefits to the investor in the form of tax benefits if the loss on a negatively geared investment is tax-deductible against the investor's other taxable income and if the capital gain on the sale is given a favourable tax treatment.

A corporate tax, also called corporation tax or company tax, is a type of direct tax levied on the income or capital of corporations and other similar legal entities. The tax is usually imposed at the national level, but it may also be imposed at state or local levels in some countries. Corporate taxes may be referred to as income tax or capital tax, depending on the nature of the tax.

An S corporation, for United States federal income tax, is a closely held corporation that makes a valid election to be taxed under Subchapter S of Chapter 1 of the Internal Revenue Code. In general, S corporations do not pay any income taxes. Instead, the corporation's income and losses are divided among and passed through to its shareholders. The shareholders must then report the income or loss on their own individual income tax returns.

A flow-through entity (FTE) is a legal entity where income "flows through" to investors or owners; that is, the income of the entity is treated as the income of the investors or owners. Flow-through entities are also known as pass-through entities or fiscally-transparent entities.

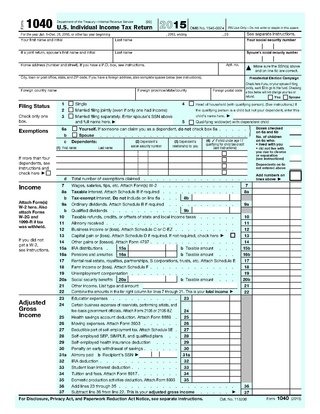

The United States federal government and most state governments impose an income tax. They are determined by applying a tax rate, which may increase as income increases, to taxable income, which is the total income less allowable deductions. Income is broadly defined. Individuals and corporations are directly taxable, and estates and trusts may be taxable on undistributed income. Partnerships are not taxed, but their partners are taxed on their shares of partnership income. Residents and citizens are taxed on worldwide income, while nonresidents are taxed only on income within the jurisdiction. Several types of credits reduce tax, and some types of credits may exceed tax before credits. Most business expenses are deductible. Individuals may deduct certain personal expenses, including home mortgage interest, state taxes, contributions to charity, and some other items. Some deductions are subject to limits, and an Alternative Minimum Tax (AMT) applies at the federal and some state levels.

Income taxes in Canada constitute the majority of the annual revenues of the Government of Canada, and of the governments of the Provinces of Canada. In the fiscal year ending March 31, 2018, the federal government collected just over three times more revenue from personal income taxes than it did from corporate income taxes.

Tax deferral refers to instances where a taxpayer can delay paying taxes to some future period. In theory, the net taxes paid should be the same. Taxes can sometimes be deferred indefinitely, or may be taxed at a lower rate in the future, particularly for deferral of income taxes.

Corporate tax is imposed in the United States at the federal, most state, and some local levels on the income of entities treated for tax purposes as corporations. Since January 1, 2018, the nominal federal corporate tax rate in the United States of America is a flat 21% following the passage of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017. State and local taxes and rules vary by jurisdiction, though many are based on federal concepts and definitions. Taxable income may differ from book income both as to timing of income and tax deductions and as to what is taxable. The corporate Alternative Minimum Tax was also eliminated by the 2017 reform, but some states have alternative taxes. Like individuals, corporations must file tax returns every year. They must make quarterly estimated tax payments. Groups of corporations controlled by the same owners may file a consolidated return.

Taxes in Iceland are levied by the state and the municipalities. Property rights are strong and Iceland is one of the few countries where they are applied to fishery management. Taxpayers pay various subsidies to each other, similar to European countries that are welfare states, but the spending is less than in most European countries. Despite low tax rates in relation to European welfare states, overall taxation and consumption is still much higher than in countries such as Ireland. Employment regulations are relatively flexible. The tax is collected by Skatturinn, the Iceland Revenue and Customs Agency and is due in March each year.

The alternative minimum tax (AMT) is a tax imposed by the United States federal government in addition to the regular income tax for certain individuals, estates, and trusts. As of tax year 2018, the AMT raises about $5.2 billion, or 0.4% of all federal income tax revenue, affecting 0.1% of taxpayers, mostly in the upper income ranges.

Taxes in Germany are levied at various government levels: the federal government, the 16 states (Länder), and numerous municipalities (Städte/Gemeinden). The structured tax system has evolved significantly, since the reunification of Germany in 1990 and the integration within the European Union, which has influenced tax policies. Today, income tax and Value-Added Tax (VAT) are the primary sources of tax revenue. These taxes reflect Germany's commitment to a balanced approach between direct and indirect taxation, essential for funding extensive social welfare programs and public infrastructure. The modern German tax system accentuate on fairness and efficiency, adapting to global economic trends and domestic fiscal needs.

Taxation in Estonia consists of state and local taxes. A relatively high proportion of government revenue comes from consumption taxes whilst revenue from capital taxes is one of the lowest in the European Union.

In Slovakia, taxes are levied by the state and local governments. Tax revenue stood at 19.3% of the country's gross domestic product in 2021. The tax-to-GDP ratio in Slovakia deviates from OECD average of 34.0% by 0.8 percent and in 2022 was 34.8% which ranks Slovakia 19th in the tax-to-GDP ratio comparison among the OECD countries. The most important revenue sources for the state government are income tax, social security, value-added tax and corporate tax.

Taxation in Belgium consists of taxes that are collected on both state and local level. The most important taxes are collected on federal level, these taxes include an income tax, social security, corporate taxes and value added tax. At the local level, property taxes as well as communal taxes are collected. Tax revenue stood at 48% of GDP in 2012.