Related Research Articles

Ys, also spelled Is or Kêr-Is in Breton, and Ville d'Ys in French, is a mythical city on the coast of Brittany that was swallowed up by the ocean. Most versions of the legend place the city in the Baie de Douarnenez.

Morgan le Fay, alternatively known as Morgan[n]a, Morgain[a/e], Morgant[e], Morg[a]ne, Morgayn[e], Morgein[e], and Morgue[in] among other names and spellings, is a powerful and ambiguous enchantress from the legend of King Arthur, in which most often she and he are siblings. Early appearances of Morgan in Arthurian literature do not elaborate her character beyond her role as a goddess, a fay, a witch, or a sorceress, generally benevolent and connected to Arthur as his magical saviour and protector. Her prominence increased as the legend of Arthur developed over time, as did her moral ambivalence, and in some texts there is an evolutionary transformation of her to an antagonist, particularly as portrayed in cyclical prose such as the Lancelot-Grail and the Post-Vulgate Cycle. A significant aspect in many of Morgan's medieval and later iterations is the unpredictable duality of her nature, with potential for both good and evil.

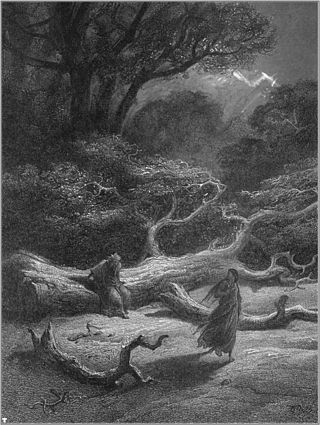

Brocéliande, earlier known as Brécheliant and Brécilien, is a legendary enchanted forest that had a reputation in the medieval European imagination as a place of magic and mystery. Brocéliande is featured in several medieval texts, mostly these related to the Arthurian legend, as well as in numerous modern works.

Paul Sébillot was a French folklorist, painter, and writer. Many of his works are about his native province, Brittany.

Dahut, also spelled Dahud, is a princess in Breton legend and literature, associated with the legend of the drowned city of Ys.

Princess Belle-Etoile is a French literary fairy tale written by Madame d'Aulnoy. Her source for the tale was Ancilotto, King of Provino, by Giovanni Francesco Straparola.

Graciosa and Percinet is a French literary fairy tale by Madame d'Aulnoy. Andrew Lang included it in The Red Fairy Book.

Morgan may refer to:

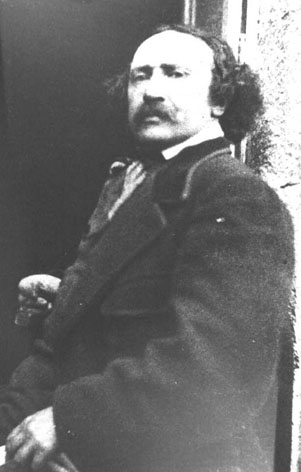

François-Marie Luzel, often known by his Breton name Fañch an Uhel, was a French folklorist and Breton-language poet.

Cornish mythology is the folk tradition and mythology of the Cornish people. It consists partly of folk traditions developed in Cornwall and partly of traditions developed by Britons elsewhere before the end of the first millennium, often shared with those of the Breton and Welsh peoples. Some of this contains remnants of the mythology of pre-Christian Britain.

Anatole le Braz, the "Bard of Brittany", was a Breton poet, folklore collector, and translator. He was highly regarded amongst both European and American scholars, and was known for his warmth and charm.

Morgan is a name of Welsh and Breton origin. Traditionally, it is a masculine-coded name in Wales and Brittany, but has been decoupled from its traditional gender outside of its regions of origin. It spread in popularity outside of Welsh and Breton communities during the past century, including in France, and in English-speaking countries worldwide. Morgan is also used as a surname, derived from the given name.

The asrai is a type of aquatic fairy in English folklore and literature. They are usually depicted as female, live in lakes and are similar to the mermaid and nixie. Rather than originating from folklore, the asrai may have been invented by the Scottish poet Robert Williams Buchanan.

Françoise Morvan is a French writer who specialises in Breton history and culture.

Le Foyer breton is a collection of Breton stories by Émile Souvestre, written in French and published in 1844. This work is a collection of Breton folktales arranged by their place of origin. It was an immediate success, becoming the foremost work of prose narrative in Brittany and inspiring several of the writer Ernest du Laurens de la Barre's works. It has been republished several times.

A groac'h is a kind of Breton water-fairy. Seen in various forms, often by night, many are old, similar to ogres and witches, sometimes with walrus teeth. Supposed to live in caverns, under the beach and under the sea, the groac'h has power over the forces of nature and can change its shape. It is mainly known as a malevolent figure, largely because of Émile Souvestre's story La Groac'h de l'île du Lok, in which the fairy seduces men, changes them into fish and serves them as meals to her guests, on one of the Glénan Islands. Other tales present them as old solitary fairies who can overwhelm with gifts the humans who visit them.

Guiomar is the best known name of a character appearing in many medieval texts relating to the Arthurian legend, often in relationship with Morgan le Fay or a similar fairy queen type character.

The Tréo-Fall, also known as danserien-noz, are lutin-like creatures from the folklore of Lower Brittany. Under this first name, they are specific to the island of Ushant, where traditions about them were collected by François-Marie Luzel.

Houles fairies are fairies specific to the Channel coast, stretching from Cancale to Tréveneuc in Upper Brittany, to the Channel Islands, and known from a few fragments of stories in the Cotentin region. They live in coastal caves and caverns known as houles. Reputed to be magnificent, immortal and very powerful, they are sensitive to salt. Rather benevolent, the swell fairies described in local stories live in communities, do their own laundry, bake their own bread or tend their own flocks, marry male fairies and are served by warrior goblins called Fions. They come to the aid of humans in many ways, providing food and enchanted objects, but get angry if anyone disrespects them or acquires the power to see their disguises without their consent.

The presence of horses in Breton culture is reflected in the strong historical attachment of the Bretons to this animal, and in religious and secular traditions, sometimes seen from the outside as part of local folklore. Probably revered since ancient times, the horse is the subject of rites, witchcraft, proverbs and numerous superstitions, sometimes involving other animals.

References

- ↑ Rhys, John (1901). Celtic folklore, Welsh and Manx , Volume 1 p. 373.

- ↑ Chambers, E. K. (1927) Arthur of Britain page 220.

- ↑ Coyajee, Jehangir Cooverjee (1939). Iranian & Indian Analogues of the Legend of the Holy Grail. p. 12.

- ↑ Rhys, John (1891) Studies in the Arthurian Legend Clarendon Press, Oxford, p. 348.

- ↑ Sykes, Egerton and Kendall, Alan (2002 ed.) Who's Who in Non-Classical Mythology Routledge, New York, p. 132.

- ↑ Paton, Lucy Allen (1903). Studies in the Fairy Mythology of Arthurian Romance. Ginn. p. 11.

- ↑ Simpson, Jacqueline, and Stephen Roud (2000). A Dictionary of English Folklore. Oxford University Press.

- ↑ Briggs, Katharine Mary and Ruth Tongue *1965). Folktales of England. University of Chicago Press.

- ↑ Tongue, Ruth L. (1970) Forgotten Folk-Tales of the English Counties Routledge & Kegan Paul, London, p. 27.

- ↑ Sébillot, Paul (1904). Le Folk-lore de France , p. 121

- ↑ Sébillot, Paul (1904). Le Folk-lore de France , pp.34-36

- ↑ Franklin, Anna (2002) The Illustrated Encyclopaedia Of Fairies Vega, London, p. 182.

- ↑ The Celtic Review, Volume 3. Norman MacLeod (1905). p. 344.

- ↑ Sébillot, Paul (1904). Le Folk-lore de France , pp.34-35

- ↑ Sébillot, Paul (1904). Le Folk-lore de France , p.36

- ↑ Luzel, François-Marie. Contes populaires de Basse-Bretagne . Tome II. Paris: Maisonneuve, 1887. pp. 257-268.

- ↑ Sébillot, Paul. Contes des provinces de France . Paris: Cerf, 1884. pp. 81-87.

- ↑ Classic folk tales from around the world. London: Leopard, 1996. pp. 128-129.

- ↑ Luzel, François-Marie (1881) Contes populaires de Basse-Bretagne. page 257.