Related Research Articles

Aos sí is the Irish name for a supernatural race in Celtic mythology—daoine sìth in Scottish Gaelic—comparable to fairies or elves. They are said to descend from the Tuatha Dé Danann, meaning the 'People of Danu', according to pagan tradition.

A kelpie, or water kelpie, is a shape-shifting spirit inhabiting lochs in Irish and Scottish folklore. It is usually described as a grey or white horse-like creature, able to adopt human form. Some accounts state that the kelpie retains its hooves when appearing as a human, leading to its association with the Christian idea of Satan as alluded to by Robert Burns in his 1786 poem "Address to the Devil".

The fili, plural filid, filidh, was a member of an elite class of poets in Ireland, and later Scotland, up until the Renaissance. The filid were believed to have the power of divination, and therefore able to foresee, foretell, predict – important events.

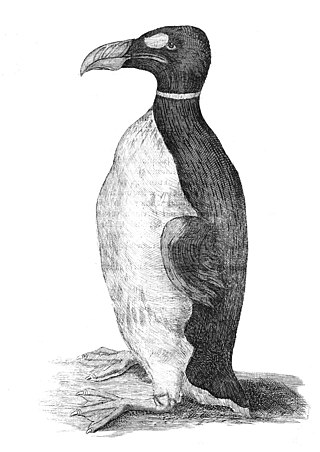

The boobrie is a mythological shapeshifting entity inhabiting the lochs of the west coast of Scotland. It commonly adopts the appearance of a gigantic water bird resembling a cormorant or great northern diver, but it can also materialise in the form of various other mythological creatures such as a water bull.

Scottish mythology is the collection of myths that have emerged throughout the history of Scotland, sometimes being elaborated upon by successive generations, and at other times being rejected and replaced by other explanatory narratives.

A fuath is a class of malevolent spirits in Scottish Highland folklore, especially water spirits.

The each-uisge is a water spirit in Irish and Scottish folklore, spelled as the each-uisce in Ireland and cabbyl-ushtey on the Isle of Man. It usually takes the form of a horse, and is similar to the kelpie but far more vicious.

The cù-sìth(e), plural coin-shìth(e) is a mythical hound found in Irish folklore and Scottish folklore. In Irish folklore it is spelled cú sídhe, and it also bears some resemblance to the Welsh Cŵn Annwn.

The glaistig is a ghost from Scottish mythology, a type of fuath. It is also known as maighdean uaine, and may appear as a woman of beauty or monstrous mien, as a half-woman and half-goat similar to a faun or satyr, or in the shape of a goat. The lower goat half of her hybrid form is usually disguised by a long, flowing green robe or dress, and the woman often appears grey with long yellow hair.

Glashtyn is a legendary creature from Manx folklore.

Gigelorum is an insect of Scottish folklore. It was believed to be the smallest creature. No description or information is available about it except that it inhabits the ear of a mite.

The Inner and Outer Hebrides off the western coast of Scotland are made up of a great number of large and small islands. These isolated islands are the source of a number of Hebridean myths and legends. The Hebridean Islands are a part of Scotland that have always relied on the surrounding sea to sustain the small communities which have occupied parts of the islands for centuries, resulting in a number of sea legends relating to these local islands.

The caoineag is a female spirit in Scottish folklore and a type of Highland banshee, her name meaning "weeper". She is normally invisible and foretells death in her clan by lamenting in the night at a waterfall, stream or Loch, or in a glen or on a mountainside. Unlike the related death portent known as the bean nighe, the caoineag cannot be approached, questioned, or made to grant wishes.

A nuggle, njuggle, or neugle, is a mythical water horse of primarily Shetland folklore where it is also referred to as a shoepultie or shoopiltee on some parts of the islands. A nocturnal creature that is always of a male gender, there are occasional fleeting mentions of him connected with the Orkney islands but he is more frequently associated with the rivers, streams and lochs of Shetland. He is easily recognised by his distinctive wheel-like tail and, unlike his evil counterparts the each-uisge or the nuckelavee, has a fairly gentle disposition being more prone to playing pranks and making mischief rather than having malicious intents.

In Scottish folklore the Ghillie Dhu or Gille Dubh was a solitary male fairy. He was kind and reticent, yet sometimes wild in character. He had a gentle devotion to children. Dark-haired and clothed in leaves and moss, he lived in a birch wood within the Gairloch and Loch a Druing area of the north-west Highlands of Scotland. Ghillie Dhu is the eponym for the ghillie suit.

A water horse is a mythical creature, such as the Ceffyl Dŵr, Capaill Uisce, the bäckahäst and kelpie.

Many types of trees found in the Celtic nations are considered to be sacred, whether as symbols, or due to medicinal properties, or because they are seen as the abode of particular nature spirits. Historically and in folklore, the respect given to trees varies in different parts of the Celtic world. On the Isle of Man, the phrase 'fairy tree' often refers to the elder tree. The medieval Welsh poem Cad Goddeu is believed to contain Celtic tree lore, possibly relating to the crann ogham, the branch of the ogham alphabet where tree names are used as mnemonic devices.

John Gregorson Campbell was a Scottish folklorist and Free Church minister at the Tiree and Coll parishes in Argyll, Scotland. An avid collector of traditional stories, he became Secretary to the Ossianic Society of Glasgow University in the mid-1850s. Ill health had prevented him taking up employment as a Minister when he was initially approved to preach by the Presbytery of Glasgow in 1858 and later after he was appointed to Tiree by the Duke of Argyll in 1861, parishioners objected to his manner of preaching.

The blue men of the Minch, also known as storm kelpies, are mythological creatures inhabiting the stretch of water between the northern Outer Hebrides and mainland Scotland, looking for sailors to drown and stricken boats to sink. They appear to be localised to the Minch and surrounding areas to the north and as far east as Wick, unknown in other parts of Scotland and without counterparts in the rest of the world.

In Scottish folklore, the beithir is a large snakelike creature or dragon.

References

Citations

- ↑ Dwelly (1902), p. 934

- ↑ MacKillop, James (2004), "bull", A Dictionary of Celtic Mythology (online ed.), Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-860967-4 , retrieved 28 May 2014

- ↑ Dwelly (1902), p. 995

- ↑ Mackinlay (1893), p. 180

- ↑ Harris (2009)

- ↑ Campbell (1860), p. 328

- 1 2 MacKillop, James (2004), "tarbh uisge", A Dictionary of Celtic Mythology (online ed.), Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-860967-4 , retrieved 17 May 2014

- 1 2 Westwood & Kingshill (2012), p. 367

- 1 2 Gregorson Campbell (1900), p. 216

- ↑ Westwood & Kingshill (2012), p. 368

- ↑ MacKillop, James (2004), "tarroo ushtey, theroo ushta", A Dictionary of Celtic Mythology (online ed.), Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-860967-4 , retrieved 17 May 2014

- ↑ Westwood & Kingshill (2012), p. 424

- ↑ Scott (2013), p. 72

- ↑ Waldron (1744), p. 85

- ↑ Westwood & Kingshill (2012), p. 455

- ↑ Campbell (1860), pp. 334–336

- ↑ Westwood & Kingshill (2012), p. 37

- ↑ MacCulloch (1819), p. 185

- ↑ Lamont-Brown (1996), p. 19

- ↑ Westwood & Kingshill (2012), pp. 367–368

- ↑ Green (1992), p. 220

- ↑ Milton Smith (2009), p. 44

Bibliography

- Campbell, John Francis (1860), Popular tales of the West Highlands, vol. IV, Edmonston and Douglas

- Dwelly, Edward (1902), Faclair Gàidhlìg air son nan sgoiltean, vol. 3, E. MacDonald

- Green, Amanda J. (1992), Animals in Celtic Life and Myth, Psychology Press, ISBN 978-0-415-05030-2

- Gregorson Campbell, John (1900), Superstitions of the Highlands and Islands of Scotland, James MacLehose

- Harris, Jason Marc (2009), "Perilous Shores: The Unfathomable Supernaturalism of Water in 19th-Century Scottish Folklore", Mythlore, 28 (1–2)[ dead link ]

- MacCulloch, John (1819), A Description of the Western Islands of Scotland, including the Isle of Man, vol. II, Moyes

- Lamont-Brown, Raymond (1996), Scottish Folklore, Birlinn, ISBN 978-1-874744-58-0

- Mackinlay, James M. (1893), Folklore Of Scottish Lochs And Springs, W. Hodge, ISBN 978-0-7661-8333-9

- Milton Smith, Charles (2009), Our Spiritual Journey: The Language of Life, Dreamstairway Books, ISBN 978-1-907091-02-5

- Scott, Walter (2013), Douglas, David (ed.), The Journal of Sir Walter Scott: Volume 2: From the Original Manuscript at Abbotsford, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-1-108-06430-9

- Waldron, George (1744), The History and Description of the Isle of Man: Viz. Its Antiquity, History, Laws, Customs, Religion and Manners of Its Inhabitants, ..., W. Bickerton

- Westwood, Jennifer; Kingshill, Sophia (2012), The Lore of Scotland: A Guide to Scottish Legends, Random House, ISBN 978-1-4090-6171-7