Related Research Articles

Hogmanay is the Scots word for the last day of the old year and is synonymous with the celebration of the New Year in the Scottish manner. It is normally followed by further celebration on the morning of New Year's Day and, in some cases, 2 January—a Scottish bank holiday. In a few contexts, the word Hogmanay is used more loosely to describe the entire period consisting of the last few days of the old year and the first few days of the new year. For instance, not all events held under the banner of Edinburgh's Hogmanay take place on 31 December.

An eponym is a person, a place, or a thing after whom or for which someone or something is, or is believed to be, named. Adjectives derived from the word eponym include eponymous and eponymic. Eponyms are commonly used for time periods, places, innovations, biological nomenclature, astronomical objects, works of art and media, and tribal names. Various orthographic conventions are used for eponyms.

A boggart is a supernatural being from English folklore. The dialectologist Elizabeth Wright described the boggart as 'a generic name for an apparition'; folklorist Simon Young defines it as 'any ambivalent or evil solitary supernatural spirit'. Halifax folklorist Kai Roberts states that boggart ‘might have been used to refer to anything from a hilltop hobgoblin to a household faerie, from a headless apparition to a proto-typical poltergeist’. As these wide definitions suggest boggarts are to be found both in and out of doors, as a household spirit, or a malevolent spirit defined by local geography, a genius loci inhabiting topographical features. The 1867 book Lancashire Folklore by Harland and Wilkinson, makes a distinction between "House boggarts" and other types. Typical descriptions show boggarts to be malevolent. It is said that the boggart crawls into people's beds at night and puts a clammy hand on their faces. Sometimes he strips the bedsheets off them. The household boggart may follow a family wherever they flee. One Lancashire source reports the belief that a boggart should never be named: if the boggart was given a name, it could neither be reasoned with nor persuaded, but would become uncontrollable and destructive.

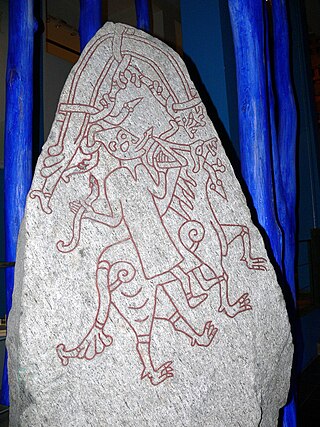

A jötunn is a type of being in Germanic mythology. In Norse mythology, they are often contrasted with gods and other non-human figures, such as dwarfs and elves, although the groupings are not always mutually exclusive. The entities included in jötunn are referred to by several other terms, including risi, þurs and troll if male and gýgr or tröllkona if female. The jötnar typically dwell across boundaries from the gods and humans in lands such as Jötunheimr.

Blackmail is a criminal act of coercion using a threat.

Yo is a slang interjection, commonly associated with North American English. It was popularized by the Italian-American community in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, in the 1940s.

A bugbear is a legendary creature or type of hobgoblin comparable to the boogeyman, and other creatures of folklore, all of which were historically used in some cultures to frighten disobedient children.

This glossary of names for the British include nicknames and terms, including affectionate ones, neutral ones, and derogatory ones to describe British people, Irish People and more specifically English, Welsh, Scottish and Northern Irish people. Many of these terms may vary between offensive, derogatory, neutral and affectionate depending on a complex combination of tone, facial expression, context, usage, speaker and shared past history.

The bogeyman is a mythical creature typically used to frighten children into good behavior. Bogeymen have no specific appearances, and conceptions vary drastically by household and culture, but they are most commonly depicted as masculine or androgynous monsters that punish children for misbehavior. The bogeyman, and conceptually similar monsters can be found in many cultures around the world. Bogeymen may target a specific act or general misbehaviour, depending on the purpose of invoking the figure, often on the basis of a warning from an authority figure to a child. The term is sometimes used as a non-specific personification of, or metonym for, terror – and sometimes the Devil.

The belfry is a structure enclosing bells for ringing as part of a building, usually as part of a bell tower or steeple. It can also refer to the entire tower or building, particularly in continental Europe for such a tower attached to a city hall or other civic building.

Ettin is an English word descended from Old English: eoten, referring to a type of being in Germanic folklore. The term may further refer to:

Folk etymology – also known as (generative) popular etymology, analogical reformation, (morphological)reanalysis and etymological reinterpretation – is a change in a word or phrase resulting from the replacement of an unfamiliar form by a more familiar one through popular usage. The form or the meaning of an archaic, foreign, or otherwise unfamiliar word is reinterpreted as resembling more familiar words or morphemes.

The word orange is a noun and an adjective in the English language. In both cases, it refers primarily to the orange fruit and the color orange, but has many other derivative meanings.

A humbug is a person or object that behaves in a deceptive or dishonest way, often as a hoax or in jest. The term was first described in 1751 as student slang, and recorded in 1840 as a "nautical phrase". It is now also often used as an exclamation to describe something as hypocritical nonsense or gibberish.

The Simonside Dwarfs, also known as Brownmen, Bogles and Duergar, are in English folklore a race of dwarfs, particularly associated with the Simonside Hills of Northumberland, in northern England. Their leader was said to be known as Heslop.

A bodach is a trickster or bogeyman figure in Gaelic folklore and mythology. The bodach "old man" is paired with the cailleach "hag, old woman" in Irish legend.

In Scotland, a wirry-cow is a bugbear, goblin, ghost, ghoul or other frightful object. Sometimes the term is used for the Devil or a scarecrow.

Draggled sae 'mang muck and stanes, They looked like wirry-cows

In the lineal kinship system used in the English-speaking world, a niece or nephew is a child of an individual's sibling or sibling-in-law. A niece is female and a nephew is male, and they would call their parents' siblings aunt or uncle. The gender-neutral term nibling has been used in place of the common terms, especially in specialist literature.

References

- 1 2 Rambles in Northumberland, and on the Scottish border ... by William Andrew Chatto, Chapman and Hall, 1835

- ↑ Lofthouse, Jessica (1976). North-country folklore in Lancashire, Cumbria and the Pennine Dales. London: Hale. ISBN 9780709153450.

- ↑ The local historian's table book, of remarkable occurrences, historical facts, traditions, legendary and descriptive ballads [&c.] connected with the counties of Newcastle-upon-Tyne, Northumberland and Durham. by Moses Aaron Richardson, M. A. Richardson, 1843

- 1 2 3 Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border by Walter Scott, Sr.

- 1 2 3 Northumberland Words – A Glossary of Words Used in the County of Northumberland and on the Tyneside -, Volume 1 by Richard Oliver Heslop, Read Books, 2008, ISBN 978-1-4097-6525-7

- ↑ Legg, Penny "The Folklore of Hampshire" The History Press (15 June 2010)

- 1 2 "Online Etymology Dictionary" . Retrieved 17 December 2014.

- ↑ Middle English Dictionary by Sherman M. Kuhn, Hans Kurath, Robert E. Lewis, University of Michigan Press, 1958, ISBN 978-0-472-01025-7, p.1212

- ↑ Merriam-Webster's collegiate dictionary, 11th edition, Merriam-Webster, 2003, ISBN 978-0-87779-809-5, p.162

- ↑ The Merriam-Webster new book of word histories, Merriam-Webster, 1991, ISBN 978-0-87779-603-9, p.71

- ↑ Metatony in Baltic, Volume 6 of Leiden studies in Indo-European by Rick Derksen, Rodopi, 1996, ISBN 90-5183-990-1, ISBN 978-90-5183-990-6, p.274

- ↑ Lexical reflections inspired by Slavonic *bog : English bogey from a Slavonic root?, Brian Cooper 1, Department of Slavonic Studies, University of Cambridge, Correspondence to Department of Slavonic Studies, University of Cambridge, Sidgwick Avenue, Cambridge CB3 9DA

- ↑ "ettin". Wiktionary. 5 October 2019. Retrieved 18 April 2022.

- ↑ Robert Burns: how to know him by William Allan Neilson, The Bobbs-Merrill company, 1917

- ↑ Seven Scots Stories by Jane Helen Findlater, Ayer Publishing, 1970

- ↑ An analytic dictionary of English etymology: an introduction by Anatoly Liberman, J. Lawrence Mitchell, University of Minnesota Press, 2008 ISBN 978-0-8166-5272-3

- ↑ A Pronouncing and Etymological Dictionary of the Gaelic Language by Malcolm MacLennan, pub. Acair / Aberdeen University Press 1979

- ↑ A Midsummer Night's Dream, page xix by William Shakespeare, Ebenezer Charlton Black

- ↑ "Online Etymology Dictionary" . Retrieved 17 December 2014.

- ↑ Quoth the maven by William Safire