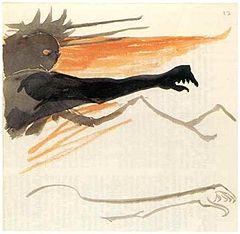

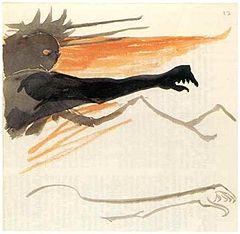

Balrogs are a species of powerful demonic monsters in J. R. R. Tolkien's Middle-earth. One first appeared in print in his high-fantasy novel The Lord of the Rings, where the Company of the Ring encounter a Balrog known as Durin's Bane in the Mines of Moria. Balrogs appear also in Tolkien's The Silmarillion and his legendarium. Balrogs are tall and menacing beings who can shroud themselves in fire, darkness, and shadow. They are armed with fiery whips "of many thongs", and occasionally use long swords.

Valinor or the Blessed Realm is a fictional location in J. R. R. Tolkien's legendarium, the home of the immortal Valar on the continent of Aman, far to the west of Middle-earth; he used the name Aman mainly to mean Valinor. It includes Eldamar, the land of the Elves, who as immortals are permitted to live in Valinor.

In the works of J. R. R. Tolkien, the Noldor are a kindred of Elves who migrate west to the blessed realm of Valinor from the continent of Middle-earth, splitting from other groups of Elves as they went. They then settle in the coastal region of Eldamar. The Dark Lord Morgoth murders their first leader, Finwë. The majority of the Noldor, led by Finwë's eldest son Fëanor, then return to Beleriand in the northwest of Middle-earth. This makes them the only group to return and then play a major role in Middle-earth's history; much of The Silmarillion is about their actions. They are the second clan of the Elves in both order and size, the other clans being the Vanyar and the Teleri.

Finwë and Míriel are fictional characters from J. R. R. Tolkien's legendarium. Finwë is the first King of the Noldor Elves; he leads his people on the journey from Middle-earth to Valinor in the blessed realm of Aman. His first wife is Míriel, who, uniquely among immortal Elves, dies while giving birth to their only child Fëanor, creator of the Silmarils; her spirit later serves the godlike Vala queen Vairë. Finwë is the first person to be murdered in Valinor: he is killed by the Dark Lord Morgoth, who is intent on stealing the Silmarils. The event sets off the Flight of the Noldor from Valinor back to Beleriand in Middle-earth, and its disastrous consequences.

Fëanor is a fictional character in J. R. R. Tolkien's The Silmarillion. He creates the Tengwar script, the palantír seeing-stones, and the three Silmarils, the skilfully forged jewels that give the book their name and theme, triggering division and destruction. He is the eldest son of Finwë, the King of the Noldor Elves, and his first wife Míriel.

In J. R. R. Tolkien's fictional legendarium, Beleriand was a region in northwestern Middle-earth during the First Age. Events in Beleriand are described chiefly in his work The Silmarillion, which tells the story of the early ages of Middle-earth in a style similar to the epic hero tales of Nordic literature, with a pervasive sense of doom over the character's actions. Beleriand also appears in the works The Book of Lost Tales, The Children of Húrin, and in the epic poems of The Lays of Beleriand.

The War of the Jewels (1994) is the 11th volume of Christopher Tolkien's series The History of Middle-earth, analysing the unpublished manuscripts of his father J. R. R. Tolkien. It is the second of two volumes—Morgoth's Ring being the first—to explore the later 1951 Silmarillion drafts.

The Shaping of Middle-earth – The Quenta, The Ambarkanta and The Annals (1986) is the fourth volume of Christopher Tolkien's 12-volume series The History of Middle-earth in which he analysed the unpublished manuscripts of his father J. R. R. Tolkien.

J. R. R. Tolkien came to feel that the flat earth cosmology he embodied in his legendarium would be unacceptable to a modern readership. In The Silmarillion, Earth was created flat and was changed to round as a cataclysmic event during the Second Age in order to prevent direct access by Men to Valinor, home of the immortals. In the Round World Version, Earth is spherical from the beginning.

In J. R. R. Tolkien's legendarium, the history of Arda, also called the history of Middle-earth, began when the Ainur entered Arda, following the creation events in the Ainulindalë and long ages of labour throughout Eä, the fictional universe. Time from that point was measured using Valian Years, though the subsequent history of Arda was divided into three time periods using different years, known as the Years of the Lamps, the Years of the Trees, and the Years of the Sun. A separate, overlapping chronology divides the history into 'Ages of the Children of Ilúvatar'. The first such Age began with the Awakening of the Elves during the Years of the Trees and continued for the first six centuries of the Years of the Sun. All the subsequent Ages took place during the Years of the Sun. Most Middle-earth stories take place in the first three Ages of the Children of Ilúvatar.

The cosmology of J. R. R. Tolkien's legendarium combines aspects of Christian theology and metaphysics with pre-modern cosmological concepts in the flat Earth paradigm, along with the modern spherical Earth view of the Solar System.

Middle-earth is the setting of much of the English writer J. R. R. Tolkien's fantasy. The term is equivalent to the Miðgarðr of Norse mythology and Middangeard in Old English works, including Beowulf. Middle-earth is the oecumene in Tolkien's imagined mythological past. Tolkien's most widely read works, The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings, are set entirely in Middle-earth. "Middle-earth" has also become a short-hand term for Tolkien's legendarium, his large body of fantasy writings, and for the entirety of his fictional world.

Morgoth Bauglir is a character, one of the godlike Valar and the primary antagonist of Tolkien's legendarium, the mythic epic published in parts as The Silmarillion, The Children of Húrin, Beren and Lúthien, and The Fall of Gondolin. The character is also briefly mentioned in The Lord of the Rings.

Sauron is the title character and the main antagonist of J. R. R. Tolkien's The Lord of the Rings, where he rules the land of Mordor. He has the ambition of ruling the whole of Middle-earth, using the power of the One Ring, which he has lost and seeks to recapture. In the same work, he is identified as the "Necromancer" of Tolkien's earlier novel The Hobbit. The Silmarillion describes him as the chief lieutenant of the first Dark Lord, Morgoth. Tolkien noted that the Ainur, the "angelic" powers of his constructed myth, "were capable of many degrees of error and failing", but by far the worst was "the absolute Satanic rebellion and evil of Morgoth and his satellite Sauron". Sauron appears most often as "the Eye", as if disembodied.

The Valar are characters in J. R. R. Tolkien's legendarium. They are "angelic powers" or "gods" subordinate to the one God. The Ainulindalë describes how some of the Ainur choose to enter the world (Arda) to complete its material development after its form is determined by the Music of the Ainur. The mightiest of these are called the Valar, or "the Powers of the World", and the others are known as the Maiar.

The Silmarillion is a book consisting of a collection of myths and stories in varying styles by the English writer J. R. R. Tolkien. It was edited, partly written, and published posthumously by his son Christopher Tolkien in 1977, assisted by Guy Gavriel Kay, who became a fantasy author. It tells of Eä, a fictional universe that includes the Blessed Realm of Valinor, the ill-fated region of Beleriand, the island of Númenor, and the continent of Middle-earth, where Tolkien's most popular works—The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings—are set. After the success of The Hobbit, Tolkien's publisher, Stanley Unwin, requested a sequel, and Tolkien offered a draft of the writings that would later become The Silmarillion. Unwin rejected this proposal, calling the draft obscure and "too Celtic", so Tolkien began working on a new story that eventually became The Lord of the Rings.

Evil is ever-present in J. R. R. Tolkien's fictional realm of Middle-earth. Tolkien is ambiguous on the philosophical question of whether evil is the absence of good, the Boethian position, or whether it is a force seemingly as powerful as good, and forever opposed to it, the Manichaean view. The major evil characters have varied origins. The first is Melkor, the most powerful of the immortal and angelic Valar; he chooses discord over harmony, and becomes the first dark lord Morgoth. His lieutenant, Sauron, is an immortal Maia; he becomes Middle-earth's dark lord after Morgoth is banished from the world. Melkor has been compared to Satan in the Book of Genesis, and to John Milton's fallen angel in Paradise Lost. Others, such as Gollum, Denethor, and Saruman – respectively, a Hobbit, a Man, and a Wizard – are corrupted or deceived into evil, and die fiery deaths like those of evil beings in Norse sagas.

J. R. R. Tolkien, a devout Roman Catholic, created what he came to feel was a moral dilemma for himself with his supposedly evil Middle-earth peoples like Orcs, when he made them able to speak. This identified them as sentient and sapient; indeed, he portrayed them talking about right and wrong. This meant, he believed, that they were open to morality, like Men. In Tolkien's Christian framework, that in turn meant they must have souls, so killing them would be wrong without very good reason. Orcs serve as the principal forces of the enemy in The Lord of the Rings, where they are slaughtered in large numbers in the battles of Helm's Deep and the Pelennor Fields in particular.

Ancalagon, or Ancalagon the Black, is a dragon that appears in the legends of British writer J. R. R. Tolkien, and particularly in his novel The Silmarillion.

The Old Straight Road, the Straight Road, the Lost Road, or the Lost Straight Road, is J. R. R. Tolkien's conception, in his fantasy world of Arda, that his Elves are able to sail to the earthly paradise of Valinor, realm of the godlike Valar. The tale is mentioned in The Silmarillion and in The Lord of the Rings, and documented in The Lost Road and Other Writings. The Elves are immortal, but may grow weary of the world, and then sail across the Great Sea to reach Valinor. The men of Númenor are persuaded by Sauron, servant of the first Dark Lord Melkor, to attack Valinor to get the immortality they feel should be theirs. The Valar ask for help from the creator, Eru Ilúvatar. He destroys Númenor and its army, in the process reshaping Arda into a sphere, and separating it and its continent of Middle-earth from Valinor so that men can no longer reach it. Elves can still set sail from the shores of Middle-earth in ships, bound for Valinor: they sail into the Uttermost West, following the Old Straight Road.