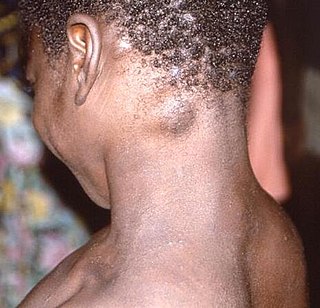

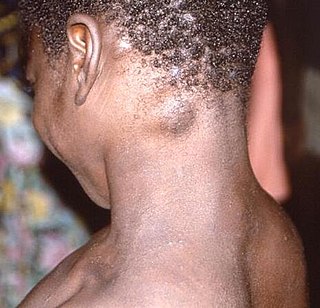

The monkeypox virus, is a species of double-stranded DNA virus that causes mpox disease in humans and other mammals. The monkeypox virus is a zoonotic virus belonging to the orthopoxvirus genus, making it closely related to the variola, cowpox, and vaccinia viruses. MPV is oval-shaped with a lipoprotein outer membrane. The genome is approximately 190 kb.

Beginning in May 2003, by July a total of 71 cases of human monkeypox were found in six Midwestern states including Wisconsin, Indiana (16), Illinois (12), Kansas (1), Missouri (2), and Ohio (1). The cause of the outbreak was traced to three species of African rodents imported from Ghana on April 9, 2003, into the United States by an exotic animal importer in Texas. These were shipped from Texas to an Illinois distributor, who housed them with prairie dogs, which then became infected.

In May 2022, the World Health Organization (WHO) made an emergency announcement of the existence of a multi-country outbreak of mpox, a viral disease then commonly known as "monkeypox". The initial cluster of cases was found in the United Kingdom, where the first case was detected in London on 6 May 2022 in a patient with a recent travel history from Nigeria. On 16 May, the UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA) confirmed four new cases with no link to travel to a country where mpox is endemic. Subsequently, cases have been reported from many countries and regions. The outbreak marked the first time mpox had spread widely outside Central and West Africa. There is evidence that the disease had been circulating and evolving in human hosts over a number of years prior to the outbreak. The outbreak was of the Clade IIb variant of the virus.

The 2022–2023 mpox outbreak in the United Kingdom is part of the larger outbreak of human mpox caused by the West African clade (type) of the monkeypox virus. The United Kingdom was the first country, outside of the endemic African areas, to experience an outbreak. As of 22 July 2022, there were 2,208 confirmed cases in the United Kingdom, with 2,115 in England, 54 in Scotland, 24 in Wales, and 15 in Northern Ireland.

The 2022–2023 mpox outbreak in the United States is part of the larger outbreak of human mpox caused by the West African clade of the monkeypox virus. The United States was the fourth country outside of the African countries with endemic mpox, to experience an outbreak in 2022. The first case was documented in Boston, Massachusetts, on May 17, 2022. As of August 22, mpox has spread to all 50 states in the United States, as well as Washington, D.C., and Puerto Rico. The United States has the highest number of mpox cases in the world. California has the highest number of mpox cases in the United States.

The 2022–2023 mpox outbreak in Canada is a part of the outbreak of human mpox caused by the West African clade of the monkeypox virus. The outbreak started in Canada on May 19, 2022, with the country since then becoming one of the most affected in the Americas.

The 2022–2023 mpox outbreak in Portugal is part of the larger outbreak of human mpox caused by the West African clade of the monkeypox virus. Portugal was the third country, outside of the African countries with endemic mpox, to experience an outbreak in 2022.

The 2022–2023 mpox outbreak in Italy is part of the larger outbreak of human mpox caused by the West African clade of the monkeypox virus. Italy was the sixth country, outside of the African countries with endemic mpox, to experience an outbreak in 2022. The first case was documented in Rome, Italy, on May 19, 2022. As of August 5th, Italy has 505 cases.

The 2022–2023 mpox outbreak in Belgium is part of the larger outbreak of human mpox caused by the West African clade of the monkeypox virus. Belgium was the fifth country, outside of the African countries with endemic mpox, to experience an outbreak in 2022. The first case was documented in Antwerp, Belgium, on 19 May 2022. As of 10 August, Belgium has 546 cases and 1 suspected case.

The 2022–2023 mpox outbreak in Australia is a part of the outbreak of human mpox caused by the West African clade of the monkeypox virus. The outbreak reached Australia on 20 May 2022. By 28 October 2022 there were over 140 confirmed cases. The Chief Medical Officer of Australia stood down the country's Communicable Disease Incident of National Significance declaration on 25 November 2022.

The 2022–2023 mpox outbreak in Israel is a part of the ongoing outbreak of human mpox caused by the West African clade of the monkeypox virus. The outbreak was first reported in Israel on 20 May 2022 when the Health Ministry announced a suspected case which was confirmed on 21 May 2022. One month later, on 21 June, the first locally transmitted case was reported.

The 2022–2023 mpox outbreak in Austria is part of the larger outbreak of human mpox caused by the West African clade of the monkeypox virus. Austria is the fifteenth country outside of Africa to experience an endemic mpox outbreak. The first case was reported in Vienna, Austria, on 22 May 2022. As of 2 December, Austria has confirmed a total of 327 cases.

The 2022–2023 mpox outbreak in Brazil is a part of the ongoing outbreak of human mpox caused by the West African clade of the monkeypox virus. The outbreak was first reported in Brazil on 9 June 2022 when a man in São Paulo was registered as the country's index case.

The 2022–2023 mpox outbreak in India is a part of the ongoing outbreak of human mpox caused by the West African clade of the monkeypox virus. The outbreak was first reported in India on 14 July 2022 when Kerala's State Health Minister Veena George announced a suspected imported case which was confirmed hours later by the NIV. India was the tenth country to report a mpox case in Asia and the first in South Asia. Currently, India has reported 23 cases of mpox.

Mpox is endemic in western and central Africa, with the majority of cases occurring in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), where the disease is reportable. There, the more virulent Congo basin virus type has been affecting some of the world's poorest and socially excluded communities.

The 2022 mpox outbreak in Asia is a part of the ongoing outbreak of human mpox caused by the West African clade of the monkeypox virus. The outbreak was reported in Asia on 20 May 2022 when Israel reported a suspected case of mpox, which was confirmed on 21 May. As of 10 August 2022, seven West Asian, three Southeast Asian, three East Asian and one South Asian country, along with Russia, have reported confirmed cases.

The 2022–2023 mpox outbreak in the Netherlands is an ongoing global outbreak which has also spread in the Netherlands. The RIVM declared the disease an A-disease which makes it mandatory to report suspected cases to the GGD. The first human case of mpox in the Netherlands has been identified at the 21 May 2022. The outbreak does have a noticeable impact at the society, especially with people spreading misinformation related to the virus. The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic in the Netherlands has increased the fear among the community for a new pandemic like mpox.

The 2022–2023 mpox outbreak in South Africa is a part of the larger outbreak of human mpox caused by the West African clade of the monkeypox virus. South Africa was the forty-seventh country, outside of the African countries with endemic mpox, to experience an outbreak in 2022. The first case of mpox in South Africa was on June 23, 2022.

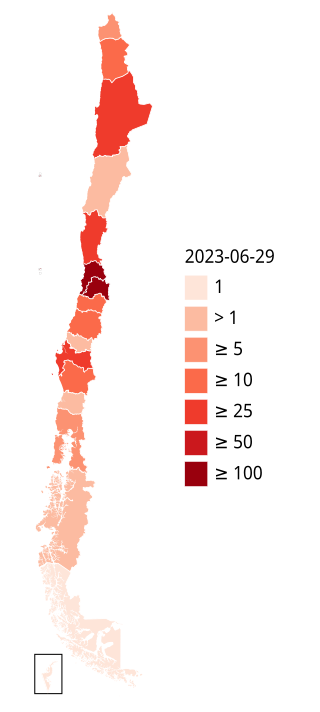

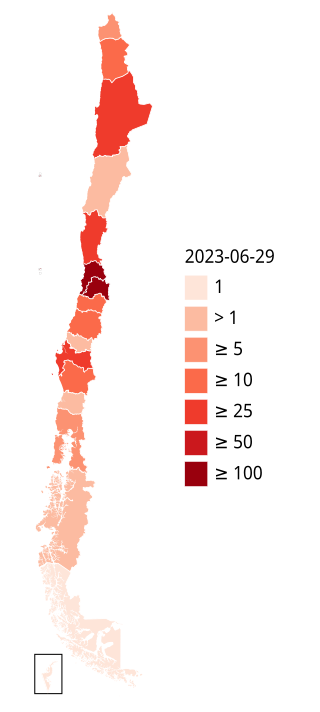

The 2022–2023 mpox outbreak in Chile is a part of the outbreak of human mpox caused by the West African clade of the monkeypox virus. The outbreak reached Chile on 17 June 2022.

The 2022–2023 mpox outbreak in Ghana is a part of the larger outbreak of human mpox caused by the West African clade of the monkeypox virus. As opposed to its West African neighbours, Ghana had no endemic presence of mpox, only experiencing it during the 2022 outbreak. The first 5 cases of mpox in Ghana was detected on June 8, 2022.