An RNA virus is a virus—other than a retrovirus—that has ribonucleic acid (RNA) as its genetic material. The nucleic acid is usually single-stranded RNA (ssRNA) but it may be double-stranded (dsRNA). Notable human diseases caused by RNA viruses include the common cold, influenza, SARS, MERS, COVID-19, Dengue virus, hepatitis C, hepatitis E, West Nile fever, Ebola virus disease, rabies, polio, mumps, and measles.

The rhinovirus is a positive-sense, single-stranded RNA virus belonging to the genus Enterovirus in the family Picornaviridae. Rhinovirus is the most common viral infectious agent in humans and is the predominant cause of the common cold.

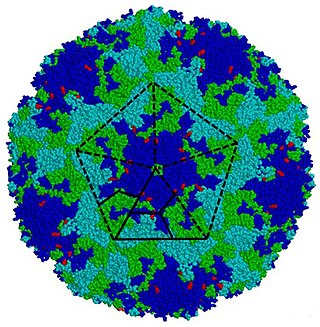

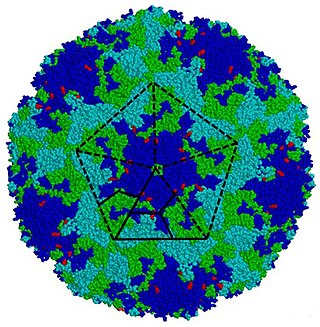

Coxsackie B4 virus are enteroviruses that belong to the Picornaviridae family. These viruses can be found worldwide. They are positive-sense, single-stranded, non-enveloped RNA viruses with icosahedral geometry. Coxsackieviruses have two groups, A and B, each associated with different diseases. Coxsackievirus group A is known for causing hand-foot-and-mouth diseases while Group B, which contains six serotypes, can cause a varying range of symptoms like gastrointestinal distress myocarditis. Coxsackievirus B4 has a cell tropism for natural killer cells and pancreatic islet cells. Infection can lead to beta cell apoptosis which increases the risk of insulitis.

Poliovirus, the causative agent of polio, is a serotype of the species Enterovirus C, in the family of Picornaviridae. There are three poliovirus serotypes, numbered 1, 2, and 3.

Hepadnaviridae is a family of viruses. Humans, apes, and birds serve as natural hosts. There are currently 18 species in this family, divided among 5 genera. Its best-known member is hepatitis B virus. Diseases associated with this family include: liver infections, such as hepatitis, hepatocellular carcinomas, and cirrhosis. It is the sole accepted family in the order Blubervirales.

Enterovirus is a genus of positive-sense single-stranded RNA viruses associated with several human and mammalian diseases. Enteroviruses are named by their transmission-route through the intestine.

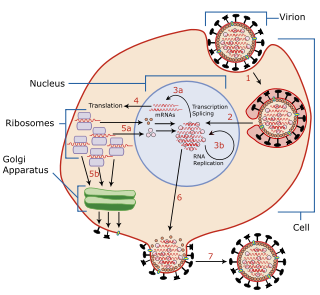

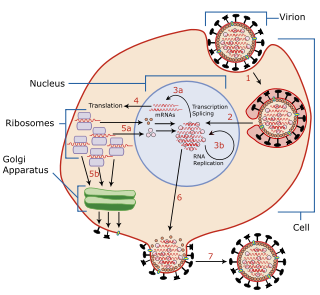

Viral replication is the formation of biological viruses during the infection process in the target host cells. Viruses must first get into the cell before viral replication can occur. Through the generation of abundant copies of its genome and packaging these copies, the virus continues infecting new hosts. Replication between viruses is greatly varied and depends on the type of genes involved in them. Most DNA viruses assemble in the nucleus while most RNA viruses develop solely in cytoplasm.

VPg is a protein that is covalently attached to the 5′ end of positive strand viral RNA and acts as a primer during RNA synthesis in a variety of virus families including Picornaviridae, Potyviridae, Astroviridae and Caliciviridae. There are some studies showing that a possible VPg protein is also present in astroviridae, however, experimental evidence for this has not yet been provided and requires further study. The primer activity of VPg occurs when the protein becomes uridylated, providing a free hydroxyl that can be extended by the virally encoded RNA-dependent RNA polymerase. For some virus families, VPg also has a role in translation initiation by acting like a 5' mRNA cap.

Aphthovirus is a viral genus of the family Picornaviridae. Aphthoviruses infect split-hooved animals, and include the causative agent of foot-and-mouth disease, Foot-and-mouth disease virus (FMDV). There are seven FMDV serotypes: A, O, C, SAT 1, SAT 2, SAT 3 and Asia 1, and four non-FMDV serotypes belonging to three additional species Bovine rhinitis A virus (BRAV), Bovine rhinitis B virus (BRBV) and Equine rhinitis A virus (ERAV).

Cardiovirus are a group of viruses within order Picornavirales, family Picornaviridae. Vertebrates serve as natural hosts for these viruses.

Parechovirus B, formerly called the Ljungan virus, was first discovered in the mid-1990s after being isolated from a bank vole near the Ljungan river in Medelpad county, Sweden. It has since been established that Parechovirus B, which is also found in several places in Europe and America, causes serious illness in wild as well as laboratory animals. Several scientific articles have recently reported findings indicating that Parechovirus B is associated with malformations, intrauterine fetal death, and sudden infant death syndrome in humans. In addition, studies are being conducted worldwide to investigate the possible connection of the virus to diabetes, neurological and other illnesses in humans.

RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) or RNA replicase is an enzyme that catalyzes the replication of RNA from an RNA template. Specifically, it catalyzes synthesis of the RNA strand complementary to a given RNA template. This is in contrast to typical DNA-dependent RNA polymerases, which all organisms use to catalyze the transcription of RNA from a DNA template.

Erbovirus is a genus of viruses in the order Picornavirales, in the family Picornaviridae. Horses serve as natural hosts. There is only one species in this genus: Erbovirus A. Diseases associated with this genus include: upper respiratory tract disease with viremia and fecal shedding. Viruses belonging to the genus Erbovirus have been isolated in horses with acute upper febrile respiratory disease. The structure of the Erbovirus virion is icosahedral, having a diameter of 27–30 nm.

This family represents the internal ribosome entry site (IRES) of the hepatitis A virus. HAV IRES is a 450 nucleotide long sequence located in the 735 nt long 5’ UTR of Hepatitis A viral RNA genome. IRES elements allow cap and end-independent translation of mRNA in the host cell. The IRES achieves this by mediating the internal initiation of translation by recruiting a ribosomal 40S pre-initiation complex directly to the initiation codon and eliminates the requirement for eukaryotic initiation factor, eIF4F.

Picornavirales is an order of viruses with vertebrate, invertebrate, protist and plant hosts. The name has a dual etymology. First, picorna- is an acronym for poliovirus, insensitivity to ether, coxsackievirus, orphan virus, rhinovirus, and ribonucleic acid. Secondly, pico-, meaning extremely small, combines with RNA to describe these very small RNA viruses. The order comprises viruses that historically are referred to as picorna-like viruses.

Eckard Wimmer is a German American virologist, organic chemist and distinguished professor of molecular genetics and microbiology at Stony Brook University. He is best known for his seminal work on the molecular biology of poliovirus and the first chemical synthesis of a viral genome capable of infection and subsequent production of live viruses.

Picornain 3C is a protease found in picornaviruses, which cleaves peptide bonds of non-terminal sequences. Picornain 3C’s endopeptidase activity is primarily responsible for the catalytic process of selectively cleaving Gln-Gly bonds in the polyprotein of poliovirus and with substitution of Glu for Gln, and Ser or Thr for Gly in other picornaviruses. Picornain 3C are cysteine proteases related by amino acid sequence to trypsin-like serine proteases. Picornain 3C is encoded by enteroviruses, rhinoviruses, aphtoviruses and cardioviruses. These genera of picoviruses cause a wide range of infections in humans and mammals.

Aichivirus A formerly Aichi virus (AiV) belongs to the genus Kobuvirus in the family Picornaviridae. Six species are part of the genus Kobuvirus, Aichivirus A-F. Within Aichivirus A, there are six different types including human Aichi virus, canine kobuvirus, murine kobuvirus, Kathmandu sewage kobuvirus, roller kobuvirus, and feline kobuvirus. Three different genotypes are found in human Aichi virus, represented as genotype A, B, and C.

Positive-strand RNA viruses are a group of related viruses that have positive-sense, single-stranded genomes made of ribonucleic acid. The positive-sense genome can act as messenger RNA (mRNA) and can be directly translated into viral proteins by the host cell's ribosomes. Positive-strand RNA viruses encode an RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) which is used during replication of the genome to synthesize a negative-sense antigenome that is then used as a template to create a new positive-sense viral genome.

Triatoma virus (TrV) is a virus belonging to the insect virus family Dicistroviridae. Within this family, there are currently 3 genera and 15 species of virus. Triatoma virus belongs to the genus Cripavirus. It is non-enveloped and its genetic material is positive-sense, single-stranded RNA. The natural hosts of triatoma virus are invertebrates. TrV is a known pathogen to Triatoma infestans, the major vector of Chagas disease in Argentina which makes triatoma virus a major candidate for biological vector control as opposed to chemical insecticides. Triatoma virus was first discovered in 1984 when a survey of pathogens of triatomes was conducted in the hopes of finding potential biological control methods for T. infestans.