History

In 1913,in the aftermath of the 1910 Edinburgh Missionary Conference,the China Continuation Committee was founded. To finalize the task of the Continuation Committee a National Christian Conference was held in Shanghai in 1922. [1] This meeting brought together more than a thousand delegates. More than half of them were Chinese Protestants,who were struggling for unity amidst theological differences between liberals and conservatives. Despite this backdrop,the Conference almost unanimously decided to form the National Christian Council. [20] The Continuation Committee was merged into the NCC and ceased to exist as an independent body,as did other organizations that had a similar fate,including China for Christ. Cheng Jingyi,who had chaired the conference,became the general secretary of NCC and remained in that position until 1933, [1] while David Z. T. Yui was made the chairman of the organization from its inception until 1928. The first annual meeting of NCC was in 1923. [21] Roman Catholics in China were not members of the NCC and had instead founded their Apostolic Delegation of China,also in 1922. [1] Later,the model of the NCC was replicated in other countries as well,Including India,Japan,Korea, [20] and the Philippines. [1]

During the early years of the NCC,its inaugural chairman David Z. T. Yui sought to balance pressure from both nationalist and anti-nationalist groups,both inside and outside the Church,although he himself favored a synthesis of nationalism and Christianity. [21] A turning point in this regard was the May Thirtieth Incident in 1925. Yu seized the opportunity to bring nationalist issues to the forefront at the NCC. [22] The NCC sided with the nationalist protesters and sent a letter to the Shanghai Municipal Council as well as a statement to foreign missionaries. The NCC stated that Christianity and patriotism are not mutually exclusive,indeed that social conscience of Christians could no longer be based on total disinterest in politics. The NCC also questioned the role of foreign missions in Chinese Christianity. [22] The viewpoint of NCC angered Western powers,including missionaries. [23] In 1926 the NCC passed numerous resolutions calling for revision of the "unequal treaties" between China and Western powers. [24]

By 1926,encouraged by anti-Western sentiments,the proportion of Chinese in the council had risen to 75% and they held the most important offices. [12] Although most Protestant missionary societies working in China were represented in the NCC, [25] it had liberal theological leanings that did not suit everybody. Conservative mission societies, [12] such as,notably,the Southern Baptists, [8] never joined the NCC. Some that had joined chose to resign later on. [12] In 1926 the China Inland Mission, [1] which had been a member of the NCC from the beginning, [26] resigned from the organization because the it had,in their view,become too liberal. The Christian and Missionary Alliance also resigned the same year,citing the same reasons. [1] Some conservatives founded the League of Christian Churches in 1929,as an alternative to the NCC. [6]

Even during the years of Nationalist China (1912–1949),the NCC suffered from lack of resources and "had no control over the larger economic,political,and security environment",a deficiency that it could not remedy,despite its active members. Some projects that were supported by the nationalist government,such as building clinics and schools,were more successful. [27] The NCC worked on education and health for many years during the Nationalist era. [2] Its efforts to educate women particularly proved effective during wartime years. [28] During that time,the NCC also took part in governmental relief efforts in the midst of many natural disasters that occurred in China in the early 1930s. [29] By 1932,70% of Protestants in China were represented by the NCC. [1]

During the Second Sino-Japanese War and World War II,the NCC was forced to temporarily relocate its headquarters from Shanghai to Chongqing. [2] The NCC's activities dwindled, [30] with the exception of continued relief work,especially among refugee children. [31] During the war,the NCC did have radio broadcast operations,in particular introducing to the audience each of its constituent churches. [7] The NCC broadcast from Shanghai on the American station XMHA. [32] The NCC's rhetoric,however,was less controversial than before the war. [30] The broadcasts were of cautious tone, [33] and avoided mentioning the Japanese by name, [34] probably to protect missionaries who were in Japanese-occupied territories. [33]

The NCC's last meeting before the war had been in 1937. [35] Much of the personnel of NCC was unable to work and it took many months after the surrender of Japan in August 1945 to have them back to the formerly Japanese-occupied areas. [36] Eventually,a meeting was convened in December 1946 and S. C. Leung emerged as the new chairman. [35] In the midst of the transition period,the NCC spoke against corruption and social injustice,but considering the handover of all political affairs to the Chinese Communist Party (CCP),this was "too little too late". Chinese Protestant churches were unable to attain a level of independence from foreign missionaries under the NCC,which would bring their loyalties under question. [37] Part of the problem was leadership. [38] In late 1930s,Wu Yi-Fang had become chairperson,Ronald Rees secretary, [1] Earl H. Cressy secretary of the commission on Christian education, [39] and Edward H. Hume was secretary of the commission on Christian medical work. Edwin Carlyle Lobenstine was honorary secretary,and T. T. Lew was head of the National Committee for Christian Religious Education in China. [40] Chen Wen-Yuan became the general secretary in 1936 and,later,honorary general secretary. [41] Historian Daniel Bays writes:"To me,it seems likely that the NCC sorely missed the leadership of Cheng Jingyi and Yu Rizhang [ David Z. T. Yui ]". Both had died in the 1930s. [38]

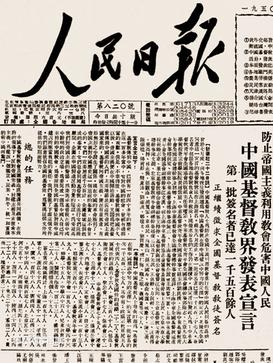

The Christian Manifesto

When the first Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC) convened in September 1949, the NCC was not invited because of its ties with Western missionaries. Instead, five progressive Christians with pro-Communist Party tendencies represented Chinese Protestants there: [42] Y. T. Wu, T. C. Chao, Deng Yuzhi, Liu Liangmo, and Zhang Xueyan. [43] The "Common Program" adopted by the CPPCC, the de facto interim constitution of the People's Republic of China, guaranteed freedom of religion. [38] In November the Protestant delegates to the CPPCC sent out teams to Northern, Northwest, East, South, and Central China to see how the freedom of religion provision was being met in practice and to explain the United Front policy. [38] [43] [44] For these teams, members chosen by the NCC were included. This marked the first time that the NCC, and indeed Chinese Christians, became involved in the united front controlled by the CCP. [45] Upon their return, they planned to write a report about the situation and present it to the Chinese government. [38] Wu also briefed the NCC, informing them about the imminent founding of the Religious Affairs Division (RAD, later renamed State Administration for Religious Affairs [46] ). [47]

Parallel with these developments the NCC published three open letters to Christians in China, two in 1948 before the PRC was established and one on 10 December 1949. That letter reviewed Christianity’s contributions to Chinese society and called on Christians to uphold social righteousness, support cooperative movements, and participate in reconstruction efforts. [48] NCC leaders decided, in a 26 January meeting, to convene a national congress on 19–27 August to consider how to respond to developments including those involving the CPPCC and the RAD. [49] One proposal, in reaction to the founding of RAD was to consolidate the NCC's powers to form a Christian organization matching RAD. [50] There were concerns that the NCC would turn into a battleground of factions that wanted it either to stay independent or be subjected to the government of China. [51] By late summer of 1950, "The Christian Manifesto" had become part of a campaign to establish the Three-Self Patriotic Movement (TSPM) to replace the NCC, the TSPM being a more introvert organization. [52]

Proponents of "The Christian Manifesto," in order to further its prospects of success, pushed to postpone the meeting, which eventually was held 17–25 October 1950. [52] The preparatory committee of the meeting tried to fend off attempts to have the manifesto endorsed at the meeting, [51] and even planned writing a counter-manifesto. Their efforts failed, [53] and even though the TSPM was not even on the agenda of the meeting, the committee ended up unanimously supporting the manifesto and the TSPM, effectively ceding leadership to that organization. [52] It was the first meeting in history where all Chinese Protestants were represented, and so its signing of the manifesto was of special importance. From that point on the road was open for both the inception of the TSPM and the acceptance of the manifesto by Protestants. [54] For some, it was this moment rather than the initial publication that marked the manifesto's transforming of Chinese Christianity. [51]

During the course of the early 1950s, the NCC became inoperative as the TSPM took over key positions in Chinese Protestant leadership. [40] Foreign missionaries were surprised by the success of "The Christian Manifesto" and its subsequent impact on the missionary field. They were surprised by the ability of a relatively small number of activists to bypass the NCC, which at the time had massive resources and manpower behind it. [42] The NCC was, after all, the highest Protestant authority in the country. [55] Those most influential in promoting the Manifesto had been Protestants who were not affiliated with mainline churches, but with backgrounds in the YMCA and YWCA and whose role the missionaries consequentially failed to grasp. [56] The NCC's relations with Westerners began to be called into question. [57] In April 1951, the RAD initiated the Denunciation Movement which lasted until 1953. During it, the NCC was outright condemned. [58] Foreign missionaries were no longer tolerated either and they had to leave China. Those who had not left by the time the Denunciation Movement was in full swing were caught in it. [3] Because contacts and funding from foreign missionary boards was cut, the NCC had by the end of 1951 become "for all intents and purposes self-administering, self-supporting and self-propagating" – the Three-self principles of the TSPM. [59]

The history of the NCC has been interpreted in various ways: as either an example of genuine Chinese ecumenism, as a precursor to the Three-Self Patriotic Movement (TSPM), or as a tool of Western missionary societies. [60] According to Bays:

In retrospect, it appears that the NCC was a prestigious but basically powerless body which, its supporters hoped, would be effective doing informal or semiformal brokering between various constituencies of the Chinese Protestant world. It would function as a roundtable, a venue where the voices of the entire Christian community could be heard. But, hoped many ... it would also accrue prestige and power over time, and eventually have more than token powers. [61]