Aetosaurs are heavily armored reptiles belonging to the extinct order Aetosauria. They were medium- to large-sized omnivorous or herbivorous pseudosuchians, part of the branch of archosaurs more closely related to crocodilians than to birds and other dinosaurs. All known aetosaurs are restricted to the Late Triassic, and in some strata from this time they are among the most abundant fossil vertebrates. They have small heads, upturned snouts, erect limbs, and a body ornamented with four rows of plate-like osteoderms. Aetosaur fossil remains are known from Europe, North and South America, parts of Africa, and India. Since their armoured plates are often preserved and are abundant in certain localities, aetosaurs serve as important Late Triassic tetrapod index fossils. Many aetosaurs had wide geographic ranges, but their stratigraphic ranges were relatively short. Therefore, the presence of particular aetosaurs can accurately date a site in which they are found.

Gracilisuchus is an extinct genus of tiny pseudosuchian from the Late Triassic of Argentina. It contains a single species, G. stipanicicorum, which is placed in the clade Suchia, close to the ancestry of crocodylomorphs. Both the genus and the species were first described by Alfred Romer in 1972.

Lagerpeton is a genus of lagerpetid avemetatarsalian, comprising a single species, L. chanarensis. First described from the Chañares Formation of Argentina by A. S. Romer in 1971, Lagerpeton's anatomy is somewhat incompletely known, with fossil specimens accounting for the pelvic girdle, hindlimbs, posterior presacral, sacral and anterior caudal vertebrae. Skull and shoulder material has also been described.

Lewisuchus is a genus of archosaur that lived during the Late Triassic. As a silesaurid dinosauriform, it was a member of the group of reptiles most commonly considered to be the closest relatives of dinosaurs. Lewisuchus was about 1 metre (3.3 ft) long. Fossils have been found in the Chañares Formation of Argentina. It exhibited osteoderms along its back.

Calyptosuchus is an extinct genus of aetosaur from the Late Triassic of North America. Like other aetosaurs, it was heavily armored and had a pig-like snout used to uproot plants.

Doswellia is an extinct genus of archosauriform from the Late Triassic of North America. It is the most notable member of the family Doswelliidae, related to the proterochampsids. Doswellia was a low and heavily built carnivore which lived during the Carnian stage of the Late Triassic. It possesses many unusual features including a wide, flattened head with narrow jaws and a box-like rib cage surrounded by many rows of bony plates. The type species Doswellia kaltenbachi was named in 1980 from fossils found within the Vinita member of the Doswell Formation in Virginia. The formation, which is found in the Taylorsville Basin, is part of the larger Newark Supergroup. Doswellia is named after Doswell, the town from which much of the taxon's remains have been found. A second species, D. sixmilensis, was described in 2012 from the Bluewater Creek Formation of the Chinle Group in New Mexico; however, this species was subsequently transferred to a separate doswelliid genus, Rugarhynchos. Bonafide Doswellia kaltenbachi fossils are also known from the Chinle Formation of Arizona.

Proterochampsidae is a family of proterochampsian archosauriforms. Proterochampsids may have filled an ecological niche similar to modern crocodiles, and had a general crocodile-like appearance. They lived in what is now South America in the Middle and Late Triassic.

Turfanosuchus is a genus of archosauriform reptile, likely a gracilisuchid archosaur, which lived during the Middle Triassic (Anisian) of northwestern China. The type species, T. dabanensis, was described by C.C. Young in 1973, based on a partially complete but disarticulated fossil skeleton found in the Kelamayi Formation of the Turfan Basin.

Luperosuchus is an extinct genus of loricatan pseudosuchian reptile which contains only a single species, Luperosuchus fractus. It is known from the Chañares Formation of Argentina, within strata belonging to the latest Ladinian stage of the late Middle Triassic, or the earliest Carnian of the Late Triassic. Luperosuchus was one of the largest carnivores of the Chañares Formation, although its remains are fragmentary and primarily represented by a skull with similarities to Prestosuchus and Saurosuchus.

Chanaresuchus is an extinct genus of proterochampsid archosauriform. It was of modest size for a proterochampsian, being on average just over a meter in length. The type species is Chanaresuchus bonapartei was named in 1971. Its fossils were found in from the early Carnian-age Chañares Formation in La Rioja Province, Argentina. Chanaresuchus appears to be one of the most common archosauriforms from the Chañares Formation due to the abundance of specimens referred to the genus. Much of the material has been found by the La Plata-Harvard expedition of 1964-65. Chanaresuchus is the most well-described proterochampsid in the subfamily Rhadinosuchinae.

Vancleavea is a genus of extinct, armoured, non-archosaurian archosauriforms from the Late Triassic of western North America. The type and only known species is V. campi, named by Robert Long & Phillip A Murry in 1995. At that time, the genus was only known from fragmentary bones including osteoderms and vertebrae. However, since then many more fossils have been found, including a pair of nearly complete skeletons discovered in 2002. These finds have shown that members of the genus were bizarre semiaquatic reptiles. Vancleavea individuals had short snouts with large, fang-like teeth, and long bodies with small limbs. They were completely covered with bony plates known as osteoderms, which came in several different varieties distributed around the body. Phylogenetic analyses by professional paleontologists have shown that Vancleavea was an archosauriform, part of the lineage of reptiles that would lead to archosaurs such as dinosaurs and crocodilians. Vancleavea lacks certain traits which are present in most other archosauriforms, most notably the antorbital, mandibular and supratemporal fenestrae, which are weight-saving holes in the skulls of other taxa. However, other features clearly support its archosauriform identity, including a lack of intercentra, the presence of osteoderms, an ossified laterosphenoid, and several adaptations of the femur and ankle bones. In 2016, a new genus of archosauriform, Litorosuchus, was described. This genus resembled both Vancleavea and more typical archosauriforms in different respects, allowing Litorosuchus to act as a transitional fossil linking Vancleavea to less aberrant archosauriforms.

Rhadinosuchus is an extinct genus of proterochampsian archosauriform reptile from the Late Triassic. It is known only from the type species Rhadinosuchus gracilis, reposited in Munich, Germany. The fossil includes an incomplete skull and fragments of post-cranial material. Hosffstetter (1955), Kuhn (1966), Reig (1970) and Bonaparte (1971) hypothesized it to be synonymous with Cerritosaurus, but other characteristics suggest it is closer to Chanaresuchus and Gualosuchus, while it is certainly different from Proterochampsa and Barberenachampsa. The small size indicates it is a young animal, making it hard to classify.

Archeopelta is an extinct genus of carnivorous archosaur from the late Middle or early Late Triassic period. It was a 2 m (6 ft) long predator which lived in what is now southern Brazil. Its exact phylogenetic placement within Archosauriformes is uncertain; it was originally classified as a doswelliid, but subsequently it was argued to be an erpetosuchid archosaur.

Doswelliidae is an extinct family of carnivorous archosauriform reptiles that lived in North America and Europe during the Middle to Late Triassic period. Long represented solely by the heavily-armored reptile Doswellia, the family's composition has expanded since 2011, although two supposed South American doswelliids were later redescribed as erpetosuchids. Doswelliids were not true archosaurs, but they were close relatives and some studies have considered them among the most derived non-archosaurian archosauriforms. They may have also been related to the Proterochampsidae, a South American family of crocodile-like archosauriforms.

Proterochampsia is a clade of early archosauriform reptiles from the Triassic period. It includes the Proterochampsidae and probably also the Doswelliidae. Nesbitt (2011) defines Proterochampsia as a stem-based taxon that includes Proterochampsa and all forms more closely related to it than Euparkeria, Erythrosuchus, Passer domesticus, or Crocodylus niloticus. Therefore, the inclusion of Doswelliidae in it is dependent upon whether Doswellia and Proterochampsa form a monophyletic group to the exclusion of Archosauria and other related groups.

Erpetosuchidae is an extinct family of pseudosuchian archosaurs. Erpetosuchidae was named by D. M. S. Watson in 1917 to include Erpetosuchus. It includes the type species Erpetosuchus granti from the Late Triassic of Scotland, Erpetosuchus sp. from the Late Triassic of eastern United States and Parringtonia gracilis from the middle Middle Triassic of Tanzania; the group might also include Dyoplax arenaceus from the Late Triassic of Germany, Archeopelta arborensis and Pagosvenator candelariensis from Brazil and Tarjadia ruthae from Argentina.

Jaxtasuchus is an extinct genus of armored doswelliid archosauriform reptile known from the Middle Triassic of the Erfurt Formation in Germany. The type species, Jaxtasuchus salomoni, was named in 2013 on the basis of several incomplete skeletons and other isolated remains. Like other doswelliids, members of the genus were heavily armored, with four longitudinal rows of bony plates called osteoderms covering the body. Jaxtasuchus is the first doswelliid known from Europe and is most closely related to Doswellia from the Late Triassic of the eastern United States. However, it was not as specialized as Doswellia, retaining several generalized archosauriform characteristics and having less armor. Jaxtasuchus fossils have been found in aquatic mudstones alongside fossils of temnospondyl amphibians, crustaceans, and mollusks, suggesting that Jaxtasuchus was semiaquatic like modern crocodilians.

Nundasuchus is an extinct genus of crurotarsan, possibly a suchian archosaur related to Paracrocodylomorpha. Remains of this genus are known from the Middle Triassic Manda beds of southwestern Tanzania. It contains a single species, Nundasuchus songeaensis, known from a single partially complete skeleton, including vertebrae, limb elements, osteoderms, and skull fragments.

Aenigmaspina is an extinct genus of enigmatic pseudosuchian (=crurotarsan) archosaur from the Late Triassic of the United Kingdom. Its fossils are known from the Pant-y-ffynnon Quarry in South Wales, of which its type and only known species is named after, A. pantyffynnonensis. Aenigmaspina is characterised by the unusual spines on its vertebrae, which are broad and flat on top with a unique 'Y' shape. Although parts of its skeleton is relatively well known, the affinities of Aenigmaspina to other pseudosuchians are unclear, although it is possibly related to families Ornithosuchidae, Erpetosuchidae or Gracilisuchidae.

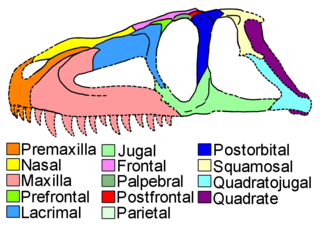

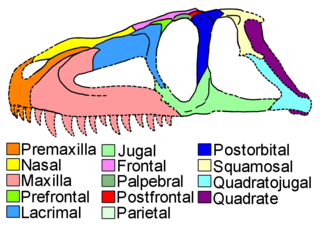

Rugarhynchos is an extinct genus of doswelliid archosauriform from the Late Triassic of New Mexico. The only known species is Rugarhynchos sixmilensis. It was originally described as a species of Doswellia in 2012, before receiving its own genus in 2020. Rugarhynchos was a close relative of Doswellia and shared several features with it, such as the absence of an infratemporal fenestra and heavily textured skull bones. However, it could also be distinguished by many unique characteristics, such as a thick diagonal ridge on the side of the snout, blunt spikes on its osteoderms, and a complex suture between the quadratojugal, squamosal, and jugal. Non-metric multidimensional scaling and tooth morphology suggest that Rugarhynchos had a general skull anatomy convergent with some crocodyliforms, spinosaurids, and phytosaurs. However, its snout was somewhat less elongated than those other reptiles.