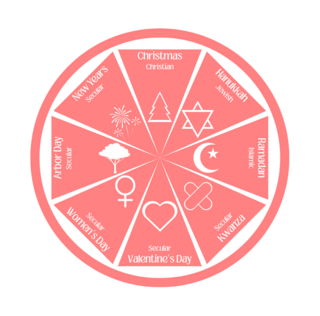

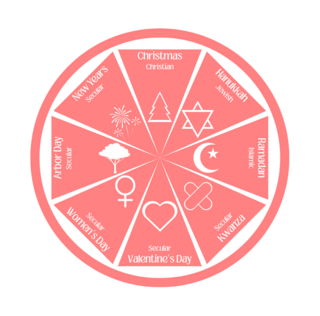

A holiday is a day or other period of time set aside for festivals or recreation. Public holidays are set by public authorities and vary by state or region. Religious holidays are set by religious organisations for their members and are often also observed as public holidays in religious majority countries. Some religious holidays, such as Christmas, have become secularised by part or all of those who observe them. In addition to secularisation, many holidays have become commercialised due to the growth of industry.

A United Nations General Assembly resolution is a decision or declaration voted on by all member states of the United Nations in the General Assembly.

The International Commission of Jurists (ICJ) is an international human rights non-governmental organization. It is a standing group of 60 eminent jurists—including senior judges, attorneys and academics—who work to develop national and international human rights standards through the law. Commissioners are known for their experience, knowledge and fundamental commitment to human rights. The composition of the Commission aims to reflect the geographical diversity of the world and its many legal systems.

Mahmoud Cherif Bassiouni was an Egyptian-American emeritus professor of law at DePaul University, where he taught from 1964 to 2012. He served in numerous United Nations positions and served as the consultant to the US Department of State and Justice on many projects. He was a founding member of the International Human Rights Law Institute at DePaul University which was established in 1990. He served as president from 1990 to 1997 and then as president emeritus. Bassiouni is often referred to by the media as "the Godfather of International Criminal Law" and a "war crimes expert". As such, he served on the Steering Committee for The Crimes Against Humanity Initiative, which was launched to study the need for a comprehensive convention on the prevention and punishment of crimes against humanity, and draft a proposed treaty. He spearheaded the drafting of the proposed convention, which as of 2014 is being debated at the International Law Commission.

The laws of state responsibility are the principles governing when and how a state is held responsible for a breach of an international obligation. Rather than set forth any particular obligations, the rules of state responsibility determine, in general, when an obligation has been breached and the legal consequences of that violation. In this way they are "secondary" rules that address basic issues of responsibility and remedies available for breach of "primary" or substantive rules of international law, such as with respect to the use of armed force. Because of this generality, the rules can be studied independently of the primary rules of obligation. They establish (1) the conditions of actions to qualify as internationally wrongful, (2) the circumstances under which actions of officials, private individuals and other entities may be attributed to the state, (3) general defences to liability and (4) the consequences of liability.

War can heavily damage the environment, and warring countries often place operational requirements ahead of environmental concerns for the duration of the war. Some international law is designed to limit this environmental harm.

In jurisprudence, reparation is replenishment of a previously inflicted loss by the criminal to the victim. Monetary restitution is a common form of reparation.

Theodoor Cornelis (Theo) van Boven is a Dutch jurist and professor emeritus in international law.

Impunity is the ability to act with exemption from punishments, losses, or other negative consequences. In the international law of human rights, impunity is failure to bring perpetrators of human rights violations to justice and, as such, itself constitutes a denial of the victims' right to justice and redress. Impunity is especially common in countries which lack the tradition of rule of law, or suffer from pervasive corruption, or contain entrenched systems of patronage, or where the judiciary is weak or members of the security forces are protected by special jurisdictions or immunities. Impunity is sometimes considered a form of denialism of historical crimes.

The Yogyakarta Principles is a document about human rights in the areas of sexual orientation and gender identity that was published as the outcome of an international meeting of human rights groups in Yogyakarta, Indonesia, in November 2006. The principles were supplemented and expanded in 2017 to include new grounds of gender expression and sex characteristics and a number of new principles. However, the Principles have never been accepted by the United Nations (UN) and the attempt to make gender identity and sexual orientation new categories of non-discrimination has been repeatedly rejected by the General Assembly, the UN Human Rights Council and other UN bodies.

United Nations Security Council resolution 1544, adopted on 19 May 2004, after recalling resolutions 242 (1967), 338 (1973), 446 (1979), 1322 (2000), 1397 (2002), 1402 (2002), 1403 (2002), 1405 (2002), 1435 (2002) and 1515 (2003), the Council called on Israel to cease demolishing Palestinian homes.

Reparations are broadly understood as compensation given for an abuse or injury. The colloquial meaning of reparations has changed substantively over the last century. In the early 1900s, reparations were interstate exchanges that were punitive mechanisms determined by treaty and paid by the surrendering side of conflict, such as the World War I reparations paid by Germany and its allies. Reparations are now understood as not only war damages but also compensation and other measures provided to victims of severe human rights violations by the parties responsible. The right of the victim of an injury to receive reparations and the duty of the part responsible to provide them has been secured by the United Nations.

Memorialization generally refers to the process of preserving memories of people or events. It can be a form of address or petition, or a ceremony of remembrance or commemoration.

The United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGPs) is an instrument consisting of 31 principles implementing the United Nations' (UN) "Protect, Respect and Remedy" framework on the issue of human rights and transnational corporations and other business enterprises. Developed by the Special Representative of the Secretary-General (SRSG) John Ruggie, these Guiding Principles provided the first global standard for preventing and addressing the risk of adverse impacts on human rights linked to business activity, and continue to provide the internationally accepted framework for enhancing standards and practice regarding business and human rights. On June 16, 2011, the United Nations Human Rights Council unanimously endorsed the Guiding Principles for Business and Human Rights, making the framework the first corporate human rights responsibility initiative to be endorsed by the UN.

The Whitney R. Harris World Law Institute at Washington University School of Law, established in 2000 as the Institute for Global Legal Studies, serves as a center for instruction and research in international and comparative law.

The term international framework of sexual violence refers to the collection of international legal instruments – such as treaties, conventions, protocols, case law, declarations, resolutions and recommendations – developed in the 20th and 21st century to address the problem of sexual violence. The framework seeks to establish and recognise the right all human beings to not experience sexual violence, to prevent sexual violence from being committed wherever possible, to punish perpetrators of sexual violence, and to provide care for victims of sexual violence. The standards set by this framework are intended to be adopted and implemented by governments around the world in order to protect their citizens against sexual violence.

Development is a human right that belongs to everyone, individually and collectively. Everyone is “entitled to participate in, contribute to, and enjoy economic, social, cultural and political development, in which all human rights and fundamental freedoms can be fully realized,” states the groundbreaking UN Declaration on the Right to Development, proclaimed in 1986.

The guarantees of non-repetition is a component of reparations as stipulated in the United Nations Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights resolution proclaiming the Basic Principles and Guidelines on the Right to a Remedy and Reparation for Victims of Gross Violations of International Human Rights Law and Serious Violations of International Humanitarian Law. Guarantees of non-repetition are post-conflict measures taken to ensure that systemic human rights abuses do not recur.

The Declaration on the Rights of Peasants is an UNGA resolution on human rights with "universal understanding", adopted by the United Nations in 2018. The resolution was passed by a vote of 121-8, with 54 members abstaining.

The eleventh emergency special session of the United Nations General Assembly opened on 28 February 2022 at the United Nations headquarters. It addresses the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Maldivian politician Abdulla Shahid served as President of the body during this time.