"Seasons in the Sun" is an English-language adaptation of the 1961 Belgian song "Le Moribond" by singer-songwriter Jacques Brel with lyrics rewritten in 1963 by singer-poet Rod McKuen portraying a dying man's farewell to his loved ones. It became a worldwide hit in 1974 for singer Terry Jacks and became a Christmas number one in the UK in 1999 for Westlife.

Claudius Afolabi Siffre, better known as Labi Siffre, is a British singer, songwriter and poet. Siffre released six albums between 1970 and 1975, and four between 1988 and 1998. His best known compositions include "It Must Be Love", which reached number 14 on the UK Singles Chart in 1971, "Crying Laughing Loving Lying", and "(Something Inside) So Strong"—an anti-apartheid song inspired by a television documentary in which white soldiers in South Africa were filmed shooting at black civilians in the street—which hit number 4 on the UK chart. The latter song won Siffre the Ivor Novello Award for Best Song Musically and Lyrically from the British Academy of Songwriters, Composers and Authors, and it has been used in Amnesty International campaigns.

"West End Girls" is a song by English synth-pop duo Pet Shop Boys. Written by Neil Tennant and Chris Lowe, the song was released twice as a single. The song's lyrics are concerned with class and the pressures of inner-city life in London which were inspired partly by T. S. Eliot's poem The Waste Land. It was generally well received by contemporary music critics and has been frequently cited as a highlight in the duo's career.

Edmond Montague Grant is a Guyanese-British singer, songwriter and multi-instrumentalist, known for his genre-blending sound and socially-conscious lyrics; his music has blended elements of pop, British rock, soul, funk, reggae, electronic music, African polyrhythms, and Latin music genres such as samba, among many others. In addition to this, he also helped to pioneer the genre of "Ringbang". He was a founding member of the Equals, one of the United Kingdom's first racially mixed pop groups who are best remembered for their million-selling UK chart-topper, the Grant-penned "Baby, Come Back".

"Ebony and Ivory" is a song that was released in 1982 as a single by Paul McCartney featuring Stevie Wonder. It was issued on 29 March that year as the lead single from McCartney's third solo album, Tug of War (1982). Written by McCartney, the song aligns the black and white keys of a piano keyboard with the theme of racial harmony. The single reached number one on both the UK and the US charts and was among the top-selling singles of 1982 in the US. During the apartheid era, the South African Broadcasting Corporation banned the song after Wonder dedicated his 1984 Academy Award for Best Original Song to Nelson Mandela.

"Gimme! Gimme! Gimme! " is a song by Swedish band ABBA. It was recorded in August 1979 in order to help promote their North American and European tour of that year, and was released on ABBA's Greatest Hits Vol. 2 album as the brand new track.

"Wild World" is a song written and recorded by English singer-songwriter Cat Stevens. It first appeared on his fourth album, Tea for the Tillerman (1970). Released as a single in September 1970 by Island Records and A&M Records, "Wild World" saw significant commercial success, garnering attention for its themes of love and heartbreak, and has been covered numerous times since its release. Maxi Priest and Mr. Big had successful cover versions of the song, released in 1988 and 1993.

"I Want It All" is a song by British rock band Queen, featured on their 1989 studio album, The Miracle. Written by guitarist and vocalist Brian May and produced by David Richards, it was released as the first single from the album on 2 May 1989. "I Want It All" reached number three on the singles charts of the United Kingdom, Finland, Ireland and New Zealand, as well as on the US Billboard Album Rock Tracks chart. Elsewhere, it peaked at number two in the Netherlands and charted within the top 10 in Australia, Belgium, Germany, Norway and Switzerland. With its message about fighting for one's own goals it became an anti-apartheid protest song in South Africa.

"Never Gonna Give You Up" is a song by English singer Rick Astley, released on 27 July 1987. Written and produced by Stock Aitken Waterman, it was released by RCA Records as the first single from Astley's debut studio album, Whenever You Need Somebody (1987). The song became a worldwide hit, initially in the United Kingdom in 1987, where it stayed at the top of the chart for five weeks and was the best-selling single of that year. It eventually topped charts in 25 different countries, including the United States and West Germany, and winning Best British Single at the 1988 Brit Awards. The song is widely regarded as Astley's most popular, as well as his signature song, and it is often played at the end of his live concerts.

"Born Slippy .NUXX" is a song by the British electronic music group Underworld. It was first released as the B-side to another track, "Born Slippy", in May 1995. The fragmented lyrics describe the perspective of an alcoholic.

"Kids in America" is a song recorded by English pop singer Kim Wilde. It was released in the United Kingdom as her debut single in January 1981, and in the United States in spring 1982, later appearing on her self-titled debut studio album. Largely inspired by the synth-pop style of Orchestral Manoeuvres in the Dark (OMD) and Gary Numan, the song reached number two on the UK Singles Chart for two weeks and number one in Finland and South Africa, and charted in the top 10 of many European charts as well as Australia and New Zealand. In North America, the song reached the top 40 in Canada and the United States. It was certified gold in the United Kingdom, South Africa, Australia and Sweden; and has sold over three million copies worldwide. The song has been covered by many artists from different genres.

"You're in the Army Now" is a song by the South African-born Dutch duo Bolland & Bolland, released in 1982. The song spent six consecutive weeks on the top of the Norwegian singles chart. A cover by British rock band Status Quo, simplified as "In the Army Now", was internationally successful in 1986.

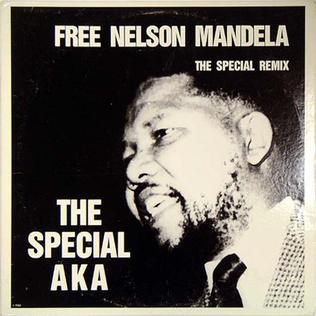

"Nelson Mandela" is a song written by British musician Jerry Dammers, and performed by the band the Special A.K.A. with a lead vocal by Stan Campbell. It was first released on the single "Nelson Mandela"/"Break Down the Door" in 1984.

"Mississippi" is a song by Dutch country pop band Pussycat. Written by Werner Theunissen and produced by Eddy Hilberts, "Mississippi" was the group's first number-one single in their home country, as well as their only number-one single in most countries worldwide. In New Zealand and South Africa, "Mississippi" was their first of two number-one singles; it was the best-selling single of 1977 in the latter nation.

File Under Rock is a 1988 album by Guyanese-British musician Eddy Grant. The album includes the song "Gimme Hope Jo'anna" which was a hit in Switzerland and New Zealand as well as "Harmless Piece of Fun" which was a minor hit in the Netherlands. The album was titled File Under Rock after years of Eddy Grant being incorrectly described as a reggae artist. In Germany, the album charted for 10 weeks reaching number 48 in 1988. The album was a larger success in New Zealand where it reached number 24 on the charts and charted for 13 weeks. In the Netherlands the album reached number 36, but was only on the charts for 4 weeks. Allmusic's Alex Henderson described the album as being mostly pop rock with slight reggae influences.

"Electric Avenue" is a song by Guyanese-British musician Eddy Grant. Written and produced by Grant, it was released on his 1982 studio album Killer on the Rampage. In the United States, with the help of the MTV music video he made, it was one of the biggest hits of 1983. The song refers to Electric Avenue in London during the 1981 Brixton riot.

"Feelings" is a song by the Brazilian singer Morris Albert, who also wrote the lyrics. Albert released "Feelings" in 1974 as a single and later included it as the title track of his 1975 debut album. The song's lyrics, recognizable by the "whoa whoa whoa" chorus, concern the singer's inability to "forget my feelings of love". Albert's original recording of the song was hugely successful, performing well internationally.

"Gimme the Light" is the first single from Jamaican dancehall musician Sean Paul's second studio album, Dutty Rock (2002). The song was originally released in Jamaica in 2001 as "Give Me the Light" and was issued internationally in 2002. "Gimme the Light" was Paul's first hit single, peaking at number seven on the US Billboard Hot 100 and becoming a top-20 hit in Canada, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom. It is the most popular hit single from the "Buzz" riddim, which was the debut hit production for Troyton Rami & Roger Mackenzie a production duo of Black Shadow Records in Miami, Florida.

"I Don't Wanna Dance" is a 1982 single by Eddy Grant. It went to number one on the UK Singles Chart and held there for three weeks in November 1982. It was later released in the United States, but only reached No. 53 on the Billboard Hot 100 in late 1983. It was later reissued as the B-side of Grant's "Electric Avenue".

There is a wide range of ways in which people have represented apartheid in popular culture. During (1948–1994) and following the apartheid era in South Africa, apartheid has been referenced in many books, films, and other forms of art and literature.