Ciguatera is a foodborne illness caused by eating certain reef fish whose flesh is contaminated with a toxin made by dinoflagellates such as Gambierdiscus toxicus which live in tropical and subtropical waters. These dinoflagellates adhere to coral, algae and seaweed, where they are eaten by herbivorous fish which in turn are eaten by larger carnivorous fish like barracudas, shark, [1] and even omnivorous fish like basses and other fish like mullet. This is called biomagnification. Affected fish may show no sign of infection or, in more advanced cases, will be weakened and visibly thin, with yellowish eyes. As well, fish may be pale or a different color than usual.

Foodborne illness is any illness resulting from the food spoilage of contaminated food, pathogenic bacteria, viruses, or parasites that contaminate food, as well as toxins such as poisonous mushrooms and various species of beans that have not been boiled for at least 10 minutes.

A toxin is a poisonous substance produced within living cells or organisms; synthetic toxicants created by artificial processes are thus excluded. The term was first used by organic chemist Ludwig Brieger (1849–1919), derived from the word toxic.

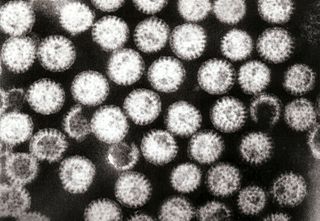

Gambierdiscus toxicus is a species of dinoflagellates that can cause ciguatera. and is known to produce several polyether marine toxins, including ciguatoxin, maitotoxin, gambieric acid, and gambierol. The species was discovered attached to the surface of brown macroalgae in the Gambier Islands, French Polynesia.

Contents

- Signs and symptoms

- Detection methods

- Folk methods

- Treatment

- Folk remedies

- Epidemiology

- Incidents in the 21st century

- History

- See also

- Footnotes

- References

Gambierdiscus toxicus is the primary dinoflagellate responsible for the production of a number of similar polyether toxins, including ciguatoxin, maitotoxin, gambieric acid and scaritoxin, as well as the long-chain alcohol palytoxin. [2] [3] Other dinoflagellates that may cause ciguatera include Prorocentrum spp., Ostreopsis spp., Coolia monotis , Thecadinium spp. and Amphidinium carterae . [4] Predator species near the top of the food chain in tropical and subtropical waters are most likely to cause ciguatera poisoning, although many other species cause occasional outbreaks of toxicity. [5]

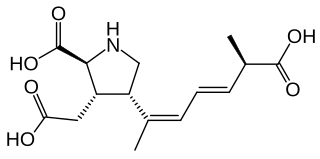

Ciguatoxins are a class of toxic polycyclic polyethers found in fish that cause ciguatera.

Maitotoxin is an extremely potent toxin produced by Gambierdiscus toxicus, a dinoflagellate species. Maitotoxin is so potent that it has been demonstrated that an intraperitoneal injection of 130 ng/kg was lethal in mice. Maitotoxin was named from the ciguateric fish Ctenochaetus striatus—called "maito" in Tahiti—from which maitotoxin was isolated for the first time. It was later shown that maitotoxin is actually produced by the dinoflagellate Gambierdiscus toxicus.

Fatty alcohols (or long-chain alcohols) are usually high-molecular-weight, straight-chain primary alcohols, but can also range from as few as 4–6 carbons to as many as 22–26, derived from natural fats and oils. The precise chain length varies with the source. Some commercially important fatty alcohols are lauryl, stearyl, and oleyl alcohols. They are colourless oily liquids (for smaller carbon numbers) or waxy solids, although impure samples may appear yellow. Fatty alcohols usually have an even number of carbon atoms and a single alcohol group (–OH) attached to the terminal carbon. Some are unsaturated and some are branched. They are widely used in industry. As with fatty acids, they are often referred to generically by the number of carbon atoms in the molecule, such as "a C12 alcohol", that is an alcohol having 12 carbons, for example dodecanol.

Ciguatoxin is odourless, tasteless and cannot be removed by conventional cooking. [6] [7]

Cooking or cookery is the art, technology, science and craft of preparing food for consumption. Cooking techniques and ingredients vary widely across the world, from grilling food over an open fire to using electric stoves, to baking in various types of ovens, reflecting unique environmental, economic, and cultural traditions and trends. The ways or types of cooking also depend on the skill and type of training an individual cook has. Cooking is done both by people in their own dwellings and by professional cooks and chefs in restaurants and other food establishments. Cooking can also occur through chemical reactions without the presence of heat, such as in ceviche, a traditional South American dish where fish is cooked with the acids in lemon or lime juice.

Researchers, such as Ross M. Brown with his "New Religion" theory suggest that ciguatera outbreaks caused by warm climatic conditions in part propelled the migratory voyages of Polynesians between 1000 and 1400AD. [8] [9]

In 2017 an updated review of "Clinical, Epidemiological, Environmental, and Public Health Management" was published and is available at the National Institute of Health website.