| Kachari | |

|---|---|

| কছাৰী | |

| Region | Assam, India |

Native speakers | 16,000 (2011) [1] |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | xac |

| Glottolog | kach1279 |

| ELP | Kachari |

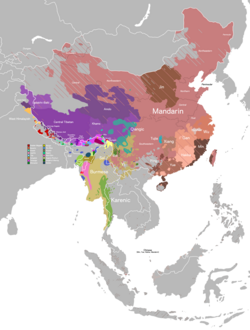

Kachari is a Sino-Tibetan language of the Boro-Garo branch that is spoken in Assam, India. With fewer than 60,000 speakers recorded in 1997, and the Asam 2001 Census reporting a literacy rate of 81% the Kachari language is currently ranked as threatened. [3] Kachari is closely related to surrounding languages, including Tiwa, Rābhā, Kochi and Mechi. [4]

Contents

- Division

- Phonology

- Consonants

- Vowels

- Prosody

- Grammar

- Syntax

- Tense

- Adjectives

- Morphology

- Number System

- References

- Bibliography

While there are still living adult speakers, many children are not learning Kachari as their primary language, instead being assimilated into the wider Assamese speaking communities. [5]