Score voting, sometimes called range voting, is an electoral system for single-seat elections. Voters give each candidate a numerical score, and the candidate with the highest average score is elected. Score voting includes the well-known approval voting, but also lets voters give partial (in-between) approval ratings to candidates.

Strategic or tactical voting is voting in consideration of possible ballots cast by other voters in order to maximize one's satisfaction with the election's results. For example, in plurality or instant-runoff, a voter may recognize their favorite candidate is unlikely to win and so instead support a candidate they think is more likely to win.

A Condorcet method is an election method that elects the candidate who wins a majority of the vote in every head-to-head election against each of the other candidates, whenever there is such a candidate. A candidate with this property, the pairwise champion or beats-all winner, is formally called the Condorcet winner. The head-to-head elections need not be done separately; a voter's choice within any given pair can be determined from the ranking.

Arrow's impossibility theorem is a key result in social choice, discovered by Kenneth Arrow, showing that no ranked voting rule can behave rationally. Specifically, any such rule violates independence of irrelevant alternatives (IIA), the idea that a choice between and should not depend on the quality of a third, unrelated option . The result is most often cited in election science and voting theory, where is called a spoiler candidate. In this context, Arrow's theorem can be restated as showing that no ranked voting rule can eliminate the spoiler effect.

The Copeland or Llull method is a ranked-choice voting system based on counting each candidate's pairwise wins and losses.

Bucklin voting is a class of voting methods that can be used for single-member and multi-member districts. As in highest median rules like the majority judgment, the Bucklin winner will be one of the candidates with the highest median ranking or rating. It is named after its original promoter, the Georgist politician James W. Bucklin of Grand Junction, Colorado, and is also known as the Grand Junction system.

Ranked Pairs (RP) is a tournament-style system of ranked voting first proposed by Nicolaus Tideman in 1987.

In an election, a candidate is called a majority winner or majority-preferred candidate if more than half of all voters would support them in a one-on-one race against any one of their opponents. Voting systems where a majority winner will always win are said to satisfy the majority-rule principle, because they extend the principle of majority rule to elections with multiple candidates.

The participation criterion, sometimes called votermonotonicity, is a voting system criterion that says candidates should never lose an election as a result of receiving too many votes in support. More formally, it says that adding more voters who prefer Alice to Bob should not cause Alice to lose the election to Bob.

The majority favorite criterion is a voting system criterion that says that, if a candidate would win more than half the vote in a first-preference plurality election, that candidate should win. Equivalently, if only one candidate is ranked first by a over 50% of voters, that candidate must win. It is occasionally referred to simply as the "majority criterion", but this term is more often used to refer to Condorcet's majority-rule principle.

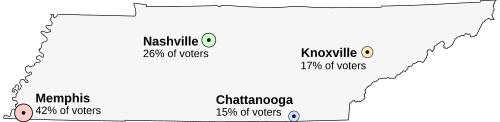

A voting system satisfies join-consistency if combining two sets of votes, both electing A over B, always results in a combined electorate that ranks A over B. It is a stronger form of the participation criterion. Systems that fail the consistency criterion are susceptible to the multiple-district paradox, which allows for a particularly egregious kind of gerrymander: it is possible to draw boundaries in such a way that a candidate who wins the overall election fails to carry even a single electoral district.

In single-winner voting system theory, the Condorcet loser criterion (CLC) is a measure for differentiating voting systems. It implies the majority loser criterion but does not imply the Condorcet winner criterion.

Anti-plurality voting describes an electoral system in which each voter votes against a single candidate, and the candidate with the fewest votes against wins. Anti-plurality voting is an example of a positional voting method.

The Kemeny–Young method is an electoral system that uses ranked ballots and pairwise comparison counts to identify the most popular choices in an election. It is a Condorcet method because if there is a Condorcet winner, it will always be ranked as the most popular choice.

Later-no-harm is a property of some ranked-choice voting systems, first described by Douglas Woodall. In later-no-harm systems, increasing the rating or rank of a candidate ranked below the winner of an election cannot cause a higher-ranked candidate to lose.

Rated, evaluative, graded, or cardinalvotingsystems are a class of voting methods which allow voters to state how strongly they support a candidate, which involves giving each one a grade on a separate scale. Cardinal methods and ordinal methods are the two categories of modern voting systems.

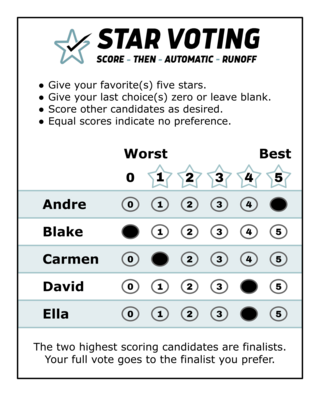

STAR voting is an electoral system for single-seat elections. The name stands for "Score then Automatic Runoff", referring to the fact that this system is a combination of score voting, to pick two finalists with the highest total scores, followed by an "automatic runoff" in which the finalist who is preferred on more ballots wins. It is a type of cardinal voting electoral system.

The highest median voting rules are a class of graded voting rules where the candidate with the highest median rating is elected.

Graduated majority judgment (GMJ), sometimes called the usual judgment or continuous Bucklin voting, is a single-winner electoral system. It was invented independently three times in the early 21st century. It was first suggested as an improvement on majority judgment by Andrew Jennings in 2010, then by Jameson Quinn, and later independently by the French social scientist Adrien Fabre in 2019. In 2024, the latter coined the name "median judgment" for the rule, arguing it was the best highest median voting rule.

Rida Laraki is a researcher, professor, and engineer in the fields of game theory, social choice, theoretical economics, optimization, learning, and operations research at the French National Centre for Scientific Research.