Marxist feminism is a philosophical variant of feminism that incorporates and extends Marxist theory. Marxist feminism analyzes the ways in which women are exploited through capitalism and the individual ownership of private property. According to Marxist feminists, women's liberation can only be achieved by dismantling the capitalist systems in which they contend much of women's labor is uncompensated. Marxist feminists extend traditional Marxist analysis by applying it to unpaid domestic labor and sex relations.

Socialist feminism rose in the 1960s and 1970s as an offshoot of the feminist movement and New Left that focuses upon the interconnectivity of the patriarchy and capitalism. However, the ways in which women's private, domestic, and public roles in society has been conceptualized, or thought about, can be traced back to Mary Wollstonecraft's A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792) and William Thompson's utopian socialist work in the 1800s. Ideas about overcoming the patriarchy by coming together in female groups to talk about personal problems stem from Carol Hanisch. This was done in an essay in 1969 which later coined the term 'the personal is political.' This was also the time that second wave feminism started to surface which is really when socialist feminism kicked off. Socialist feminists argue that liberation can only be achieved by working to end both the economic and cultural sources of women's oppression.

Monique Wittig was a French author, philosopher and feminist theorist who wrote about abolition of the sex-class system and coined the phrase "heterosexual contract". Her groundbreaking work is titled The Straight Mind and Other Essays. She published her first novel, L'Opoponax, in 1964. Her second novel, Les Guérillères (1969), was a landmark in lesbian feminism.

Critical criminology is a perspective in criminology that challenges traditional beliefs about crime and criminal justice, often by taking a conflict perspective such as Marxism, feminism, or critical theory. Critical criminology examines the genesis of crime and the nature of justice in relation to factors such as class and status, Law and the penal system are viewed as founded on social inequality and meant to perpetuate such inequality. Critical criminology also looks for possible biases in criminological research.

Standpoint feminism is a theory that feminist social science should be practiced from the standpoint of women or particular groups of women, as some scholars say that they are better equipped to understand some aspects of the world. A feminist or women's standpoint epistemology proposes to make women's experiences the point of departure, in addition to, and sometimes instead of men's.

Christine Delphy is a French feminist sociologist, writer and theorist. Known for pioneering materialist feminism, she co-founded the French women's liberation movement in 1970 and the journal Nouvelles questions féministes with Simone de Beauvoir in 1981.

Patriarchy is a social system in which positions of dominance and privilege are held by men. The term patriarchy is used both in anthropology to describe a family or clan controlled by the father or eldest male or group of males, and in feminist theory to describe a broader social structure in which men as a group dominate women and children.

Colette Guillaumin, was a sociologist at the French National Centre for Scientific Research and a French feminist. Guillaumin is an important theorist of the mechanisms of racism and sexism, and relations of domination. She is also an important figure in materialist feminism.

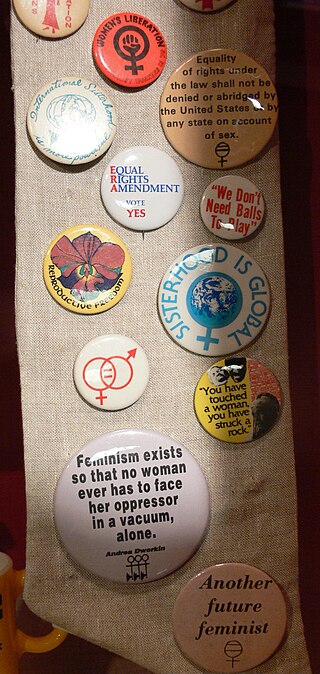

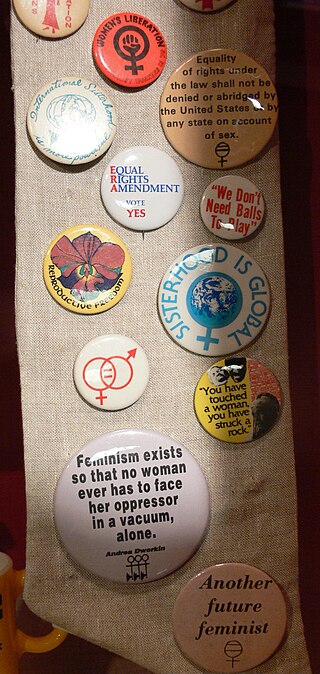

A variety of movements of feminist ideology have developed over the years. They vary in goals, strategies, and affiliations. They often overlap, and some feminists identify themselves with several branches of feminist thought.

Feminist political theory is an area of philosophy that focuses on understanding and critiquing the way political philosophy is usually construed and on articulating how political theory might be reconstructed in a way that advances feminist concerns. Feminist political theory combines aspects of both feminist theory and political theory in order to take a feminist approach to traditional questions within political philosophy.

Marxism is a method of socioeconomic analysis that originates in the works of 19th century German philosophers Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. Marxism analyzes and critiques the development of class society and especially of capitalism as well as the role of class struggles in systemic, economic, social and political change. It frames capitalism through a paradigm of exploitation and analyzes class relations and social conflict using a materialist interpretation of historical development – materialist in the sense that the politics and ideas of an epoch are determined by the way in which material production is carried on.

Poststructural feminism is a branch of feminism that engages with insights from post-structuralist thought. Poststructural feminism emphasizes "the contingent and discursive nature of all identities", and in particular the social construction of gendered subjectivities.

Marxism and the Oppression of Women: Toward a Unitary Theory is a book by the sociologist Lise Vogel that is considered an important contribution to Marxist Feminism. Vogel surveys Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels's comments on the causes of women's oppression, examines how socialist movements in Europe and in the United States have addressed women's oppression, and argues that women's oppression should be understood in terms of women's role in social reproduction and in particular in reproducing labor power.

Rosemary Hennessy is an American academic and socialist feminist. She is a Professor of English and Director of the Center for the Study of Women, Gender, and Sexuality at Rice University. She has been a part of the faculty at Rice since 2006.

Ecofeminism is a branch of feminism and political ecology. Ecofeminist thinkers draw on the concept of gender to analyse the relationships between humans and the natural world. The term was coined by the French writer Françoise d'Eaubonne in her book Le Féminisme ou la Mort (1974). Ecofeminist theory asserts a feminist perspective of Green politics that calls for an egalitarian, collaborative society in which there is no one dominant group. Today, there are several branches of ecofeminism, with varying approaches and analyses, including liberal ecofeminism, spiritual/cultural ecofeminism, and social/socialist ecofeminism. Interpretations of ecofeminism and how it might be applied to social thought include ecofeminist art, social justice and political philosophy, religion, contemporary feminism, and poetry.

This is a timeline of feminism in the United States. It contains feminist and antifeminist events. It should contain events within the ideologies and philosophies of feminism and antifeminism. It should, however, not contain material about changes in women's legal rights: for that, see Timeline of women's legal rights in the United States , or, if it concerns the right to vote, to Timeline of women's suffrage in the United States.

The following is a timeline of the history of feminism.

Lise Vogel is a feminist sociologist and art historian from the United States. An influential Marxist-feminist theoretician, she is recognised for being one of the main founders of the Social Reproduction Theory. She also participated in the civil rights and the women's liberation movements in organisations such as the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) in Mississippi and Bread & Roses in Boston. In her earlier career as an art historian, she was one of the first to try to develop a feminist perspective on Art History.

Diana Mary Leonard, AcSS, known while married as Diana Leonard Barker, was a British sociologist, social anthropologist, academic, and feminist activist. From 1998 to 2007, she was Professor of Sociology at the Institute of Education, London, after which she was Emeritus Professor of the Sociology of Education and Gender department there.

Nicole-Claude Mathieu (1937–2014) was a French anthropologist, feminist, academic and writer, who is remembered for her contributions to gender studies, including women's rights, the institution of marriage, materialist feminism and women's oppression. An active contributor to feminist journals, from 1971 she served as Chef de travaux at the Laboratoire d'anthropologie sociale where she edited the journal L'Homme while contributing many articles of her own. From 1990, she was maîtresse de conférences at the School for Advanced Studies in the Social Sciences. In June 1996, she received a doctorate honoris causa from the Université Laval.