A zawiya or zaouia is a building and institution associated with Sufis in the Islamic world. It can serve a variety of functions such a place of worship, school, monastery and/or mausoleum. In some regions the term is interchangeable with the term khanqah, which serves a similar purpose. In the Maghreb, the term is often used for a place where the founder of a Sufi order or a local saint or holy man lived and was buried. In the Maghreb the word can also be used to refer to the wider tariqa and its membership.

The Badawiyyah, Sufi tariqah, was founded in the thirteenth century in Egypt by Ahmad al-Badawi (1199-1276). As a tariqah, the Badawiyyah lacks any distinct doctrines.

In Iran, the word takyeh is mostly used as a synonym of husayniyya, although some takyehs also include a zaynabiyya or an abbasiyya, like the Takyeh Moaven-ol-Molk. Many takyehs are found in Iran, where there are takyehs in almost every city.

The Qadiriyya or the Qadiri order is a Sunni Sufi mystic order (tariqa) founded by followers of Shaiykh Syed Abdul Qadir Gilani Al-Hassani, who was a Hanbali scholar from Gilan, Iran.

A ribāṭ is an Arabic term, initially designating a small fortification built along a frontier during the first years of the Muslim conquest of the Maghreb to house military volunteers, called murabitun, and shortly after they also appeared along the Byzantine frontier, where they attracted converts from Greater Khorasan, an area that would become known as al-ʻAwāṣim in the ninth century CE.

Sufism has a history in India that has been evolving for over 1,000 years. The presence of Sufism has been a leading entity increasing the reaches of Islam throughout South Asia. Following the entrance of Islam in the early 8th century, Sufi mystic traditions became more visible during the 10th and 11th centuries of the Delhi Sultanate and after it to the rest of India. A conglomeration of four chronologically separate dynasties, the early Delhi Sultanate consisted of rulers from Turkic and Afghan lands. This Persian influence flooded South Asia with Islam, Sufi thought, syncretic values, literature, education, and entertainment that has created an enduring impact on the presence of Islam in India today. Sufi preachers, merchants and missionaries also settled in coastal Gujarat through maritime voyages and trade.

Al-Firdaws Madrasa, also known as School of Paradise, is a 13th-century complex located southwest of Bab al-Maqam in Aleppo, Syria and consists of a madrasa, mausoleum and other functional spaces. It was established in 1235/36 by Dayfa Khatun, who would later serve as the Ayyubid regent of Aleppo. It is the largest and best known of the Ayyubid madrasas in Aleppo. Due to its location outside the city walls, the madrasa was developed as a freestanding structure.

The Mosque of Abu al-Dhahab is an 18th-century mosque in Cairo, Egypt, located next to the Al-Azhar Mosque. It is a notable example of Egyptian-Ottoman architecture.

The Mosque and Khanqah of Shaykhu is an Islamic complex in Cairo built by the Grand Emir Sayf al-Din Shaykhu al-Nasiri. The mosque was built in 1349, while the khanqah was built in 1355. Shaykhu was the Grand Emir under the rule of Sultan an-Nasir Hasan.

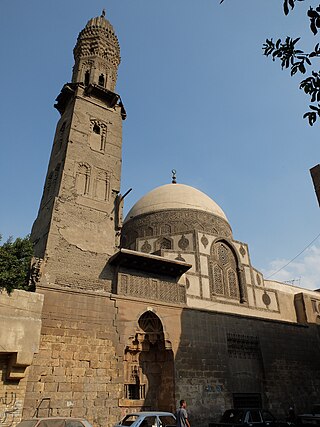

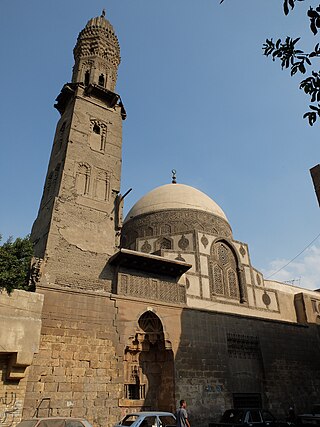

The Sultan al-Ghuri Complex or Funerary complex of Sultan al-Ghuri, also known as al-Ghuriya, is a monumental Islamic religious and funerary complex built by the Mamluk sultan Qansuh al-Ghuri between 1503 and 1505 CE. The complex consists of two major buildings facing each other on al-Mu'izz li-Din Allah street, in the Fahhamin Quarter, in the middle of the historic part of Cairo, Egypt. The eastern side of the complex includes the Sultan's mausoleum, a khanqah, a sabil, and a kuttab, while the western side of the complex is a mosque and madrasa. Today the mosque-madrasa is still open as a mosque while the khanqah-mausoleum is open to visitors as a historic site.

Mamluk architecture was the architectural style that developed under the Mamluk Sultanate (1250–1517), which ruled over Egypt, the Levant, and the Hijaz from their capital, Cairo. Despite their often tumultuous internal politics, the Mamluk sultans were prolific patrons of architecture and contributed enormously to the fabric of historic Cairo. The Mamluk period, particularly in the 14th century, oversaw the peak of Cairo's power and prosperity. Their architecture also appears in cities such as Damascus, Jerusalem, Aleppo, Tripoli, and Medina.

Hüdavendigar Mosque or Murat I, the Hüdavendigar Mosque is a historic mosque in Bursa, Turkey, that is part of the large complex (külliye) built by the Ottoman Sultan, Murad I, between 1365–1385 and is also named after the same sultan. It went under extensive renovation following the 1855 Bursa earthquake.

Mosque-Madrasa of Sultan Barquq or Mosque-Madrasa-Khanqah of Az-Zaher Barquq is a religious complex in Islamic Cairo, the historic medieval district of Cairo, Egypt. It was commissioned by Sultan al-Zahir Barquq as a school for religious education in the four Islamic schools of thought, composed of a mosque, madrasa, mausoleum and khanqah. The complex was constructed in 1384-1386 CE, with the dome added last. It was the first architectural facility built during the rule of the Circassian (Burji) dynasty of Mamluk Sultanate.

The Madrasa of Amir Sunqur Sa'di, also commonly known as the Mausoleum of (Sheikh) Hasan Sadaqa, is a medieval Mamluk-era madrasa structure and mausoleum in Cairo, Egypt. It was originally built between 1315 and 1321 CE by amir Sunqur Sa'di. Sunqur was forced to leave Egypt in his lifetime and was never buried there, but a sheikh known as Hasan Sadaqa was later buried in it and therefore the building is often known by his name. From the 17th century onward the complex was converted into Mevlevi Sufi lodge and is open today as the Mawlawiyya Museum or Museo Mevlevi.

The Sultaniyya Mausoleum is a Mamluk-era funerary complex located in the Southern Cemetery of the Qarafa, the necropolis of Cairo, Egypt. It is believed to have been built in the 1350s and dedicated to the mother of Sultan Hasan. It is notable for its unique pair of stone domes.

The Khanqah and Mausoleum of Sultan Barsbay or Complex of Sultan Barsbay is an Islamic funerary complex built by Sultan al-Ashraf Barsbay in 1432 CE in the historic Northern Cemetery of Cairo, Egypt. In addition to its overall layout and decoration, it is notable for the first stone domes in Cairo to be carved with geometric star patterns.

The Inspector's Gate is one of the gates of the al-Aqsa Compound. It is the second-northernmost gates in the compound's west wall, after the Bani Ghanim Gate. It is north of the Iron Gate.

Saʿdiyya (سعدية) or Jibawiyya (جباوية) is a Sufi tariqa and a family lineage of Syrian and Shafiʿi identity. It grew to prominence also in Ottoman Egypt, Turkey, and the Balkans and it is still active today. They are known for their distinctive rituals and their role in the social history of Damascus. Like many other tariqas, the Saʿdiyya is characterized by the practice of khawāriḳ al-ʿādāt such as healing, spectacles involving body piercing, and dawsa (trampling), for which they are best known; the sheikh would ride a horse over his dervishes, who were lying face down making a “living carpet” of men. They had a wide appeal among the middle and lower classes. The founder of Saʿdiyya was Saʿd al-Dīn al-Shaybānī al-Jibāwī, who took the tariqa from the Yūnisī and Rifaʽi lines, his dates remain uncertain, but he is thought to have died near Jibā, a few kilometers north of Damascus in 736/1335.

The at-Tankiziyya is a historic building in Jerusalem that included a madrasa. It is part of the west wall of the al-Aqsa Compound. It is also known as the Maḥkama building.

The Khalidiya Khanqah Mosque and Tekke also known as the Mzgawti Xanaqa is located near the the citadel in Erbil, Iraq. It is a religious complex comprising a mosque, Sufi lodge, library and marketplace. The site was founded in 1805, while the current structure dates back to a 1961 renovation.