A Mosque or Masjid is a place of prayer for Muslims. Mosques are usually covered buildings, but can be any place where prayers (salah) are performed, including outdoor courtyards.

The qibla is the direction towards the Kaaba in the Sacred Mosque in Mecca, which is used by Muslims in various religious contexts, particularly the direction of prayer for the salah. In Islam, the Kaaba is believed to be a sacred site built by prophets Ibrahim and Ismail, and that its use as the qibla was ordained by Allah in several verses of the Quran revealed to Muhammad in the second Hijri year. Prior to this revelation, Muhammad and his followers in Medina faced Jerusalem for prayers. Most mosques contain a mihrab that indicates the direction of the qibla.

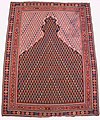

Mihrab is a niche in the wall of a mosque that indicates the qibla, the direction of the Kaaba in Mecca towards which Muslims should face when praying. The wall in which a mihrab appears is thus the "qibla wall".

The Bajrakli Mosque is a mosque in Belgrade, the capital of Serbia. It is located in Gospodar Jevremova Street in the neighbourhood of Dorćol. It was built around 1575, and is the only mosque in the city out of the 273 that had existed during the time of the Ottoman Empire's rule of Serbia.

Prayer beads are a form of beadwork used to count the repetitions of prayers, chants, or mantras by members of various religions such as Hinduism, Buddhism, Shinto, Umbanda, Islam, Sikhism, the Baháʼí Faith, and some Christian denominations, such as the Roman Catholic Church, the Lutheran Church, the Oriental Orthodox Churches, and the Eastern Orthodox Churches. Common forms of beaded devotion include the mequteria in Oriental Orthodox Christianity, the chotki in Eastern Orthodox Christianity, the Wreath of Christ in Lutheran Christianity, the Dominican rosary of the Blessed Virgin Mary in Roman Catholic Christianity, the dhikr in Islam, the japamala in Buddhism and Hinduism, and the Jaap Sahib in Sikhism.

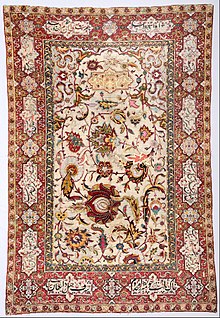

An oriental rug is a heavy textile made for a wide variety of utilitarian and symbolic purposes and produced in "Oriental countries" for home use, local sale, and export.

The city of Jerusalem is sacred to many religious traditions, including the Abrahamic religions of Judaism, Christianity and Islam which consider it a holy city. Some of the most sacred places for each of these religions are found in Jerusalem, most prominently, the Temple Mount/Haram Al-Sharif.

Sacral architecture is a religious architectural practice concerned with the design and construction of places of worship or sacred or intentional space, such as churches, mosques, stupas, synagogues, and temples. Many cultures devoted considerable resources to their sacred architecture and places of worship. Religious and sacred spaces are amongst the most impressive and permanent monolithic buildings created by humanity. Conversely, sacred architecture as a locale for meta-intimacy may also be non-monolithic, ephemeral and intensely private, personal and non-public.

The conversion of non-Islamic places of worship into mosques occurred during the life of Muhammad and continued during subsequent Islamic conquests and under historical Muslim rule. Hindu temples, Jain Temples, Christian churches, synagogues, and Zoroastrian fire temples have been converted into mosques.

Anatolian rug is a term of convenience, commonly used today to denote rugs and carpets woven in Anatolia and its adjacent regions. Geographically, its area of production can be compared to the territories which were historically dominated by the Ottoman Empire. It denotes a knotted, pile-woven floor or wall covering which is produced for home use, local sale, and export. Together with the flat-woven kilim, Anatolian rugs represent an essential part of the regional culture, which is officially understood as the Culture of Turkey today, and derives from the ethnic, religious and cultural pluralism of one of the most ancient centres of human civilisation.

Prostration is the gesture of placing one's body in a reverentially or submissively prone position. Typically prostration is distinguished from the lesser acts of bowing or kneeling by involving a part of the body above the knee, especially the hands, touching the ground.

The Masjid al-Qiblatayn, also spelt Masjid al-Qiblatain, is a mosque in Medina believed by Muslims to be the place where the final Islamic prophet, Muhammad, received the command to change the Qibla from Jerusalem to Mecca. The mosque was built by Sawad ibn Ghanam ibn Ka'ab during the year 2 AH and is one of the few mosques in the world to have contained two mihrabs in different directions.

The Podruchnik is a small prayer rug, once used in prayer by all Russian Orthodox Christians in the Tsardom of Russia before the schism of 1653 but currently in use only by the Old Believers.

Carpets of Middle-Eastern origin, either from Anatolia, Persia, Armenia, Azerbaijan, the Levant, the Mamluk state of Egypt or Northern Africa, were used as decorative features in Western European paintings from the 14th century onwards. More depictions of Oriental carpets in Renaissance painting survive than actual carpets contemporary with these paintings. Few Middle-Eastern carpets produced before the 17th century remain, though the number of these known has increased in recent decades. Therefore, comparative art-historical research has from its onset in the late 19th century relied on carpets represented in datable European paintings.

Christian prayer is an important activity in Christianity, and there are several different forms used for this practice.

Christian influences in Islam can be traced back to Eastern Christianity, which surrounded the origins of Islam. Islam, emerging in the context of the Middle East that was largely Christian, was first seen as a Christological heresy known as the "heresy of the Ishmaelites", described as such in Concerning Heresy by Saint John of Damascus, a Syriac scholar.

A breviary is a liturgical book used in Christianity for praying the canonical hours, usually recited at seven fixed prayer times.

The name Transylvanian rug is used as a term of convenience to denote a cultural heritage of 15th–17th century Islamic rugs, mainly of Ottoman origin, which have been preserved in Transylvanian Protestant churches. The corpus of Transylvanian rugs constitutes one of the largest collections of Ottoman Anatolian rugs outside the Islamic world.

Fixed prayer times, praying at dedicated times during the day, are common practice in major world religions such as Judaism, Christianity, and Islam.

Prayer in a certain direction is characteristic of many world religions, such as Judaism, Christianity, Islam and the Bahá'í Faith.