Vatican during the Savoyard era describes the relation of the Vatican to Italy, after 1870, which marked the end of the Papal States, and 1929, when the papacy regained autonomy in the Lateran Treaty, a period dominated by the Roman Question.

Vatican during the Savoyard era describes the relation of the Vatican to Italy, after 1870, which marked the end of the Papal States, and 1929, when the papacy regained autonomy in the Lateran Treaty, a period dominated by the Roman Question.

In the years that followed the revolutions of 1848, Italian nationalists – both those who wished to unify the country under the Kingdom of Sardinia and its ruling House of Savoy and those who favored a republican solution – saw the Papal States as the chief obstacle to Italian unity. Louis Napoleon, who had now seized control of France as Emperor Napoleon III, tried to play a double game, simultaneously forming an alliance with Sardinia and playing on his famous uncle's nationalist credentials on the one hand and maintaining French troops in Rome to protect the Pope's rights on the other.

After the Austro-Sardinian War of 1859, much of northern Italy was unified under the House of Savoy's government; in the aftermath, Garibaldi led a revolution that overthrew the Bourbon monarchy in the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies. Afraid that Garibaldi would set up a republican government in the south, the Sardinians petitioned Napoleon for permission to send troops through the Papal States to gain control of the Two Sicilies, which was granted on the condition that Rome was left undisturbed. In 1860, with much of the region already in rebellion against Papal rule, Sardinia conquered the eastern two-thirds of the Papal States and cemented its hold on the south. Bologna, Ferrara, Umbria, the Marches, Benevento and Pontecorvo were all formally annexed by November of the same year, and a unified Kingdom of Italy was declared. The Papal States were reduced to Latium, the immediate neighborhood of Rome.

Rome was declared Capital of Italy in March 1861, when the first Italian Parliament met in the kingdom's old capital Turin in Piemonte. However, the Italian government could not take possession of its capital because Napoleon III kept a French garrison in Rome protecting Pope Pius IX. The opportunity to eliminate the last vestige of the Papal States came when the Franco-Prussian War began in July 1870. Emperor Napoleon III had to recall his garrison from Rome for France's own defence and could no longer protect the pope. Following the collapse of the Second French Empire at the battle of Sedan, widespread public demonstrations demanded that the Italian government take Rome. King Victor Emmanuel II sent Count Gustavo Ponza di San Martino to Pius IX with a personal letter offering a face-saving proposal that would have allowed the peaceful entry of the Italian Army into Rome, under the guise of offering protection to the pope.

According to Raffaele De Cesare:

The Pope's reception of San Martino [10 September 1870] was unfriendly. Pius IX. allowed violent outbursts to escape him. Throwing the King's letter upon a table, he exclaimed, "Fine loyalty! You are all a set of vipers, of whited sepulchres, and wanting in faith." He was perhaps alluding to other letters received from the King. After, growing calmer, he exclaimed: "I am no prophet, nor son of a prophet, but I tell you, you will never enter Rome!" San Martino was so mortified that he left the next day. [1]

On 10 September, Italy declared war on the Papal States, and the Italian Army, commanded by General Raffaele Cadorna, crossed the papal frontier on 11 September and advanced slowly toward Rome, hoping that a peaceful entry could be negotiated. The Italian Army reached the Aurelian Walls on 19 September and placed Rome under a state of siege. Although the pope's tiny army was incapable of defending the city, Pius IX ordered it to put up at least a token resistance to emphasize that Italy was acquiring Rome by force and not consent. On 20 September, the Bersaglieri entered Rome and marched down Via Pia, which was subsequently renamed Via XX Settembre. Rome and Latium were annexed to the Kingdom of Italy after a plebiscite.

In Chapter XXXIV, De Cesare also made the following observations:

This event, described in Italian history books as a liberation, was taken very bitterly by the Pope. The Italian government had offered to allow the Pope to retain control of the Leonine City on the west bank of the Tiber, but Pius rejected the overture. Early the following year, the capital of Italy was moved from Florence to Rome. The Pope, whose previous residence, the Quirinal Palace, had become the royal palace of the Kings of Italy, withdrew in protest into the Vatican, where he lived as a self-proclaimed "prisoner", refusing to leave or to set foot in St. Peter's Square, and forbidding ( Non Expedit ) Catholics under pain of excommunication to participate in elections in the new Italian state.

In October, a plebiscite in Rome and the surrounding Campagna resulted in a vote for union with the Kingdom of Italy. Pius IX refused to accept this act of force majeure . He remained in his palace, describing himself as a prisoner in the Vatican. However, the new Italian control of Rome did not wither, nor did the Catholic world come to the Pope's aid as Pius IX had expected.

The provisional capital of Italy had been Florence since 1865. In 1871, the Italian government moved to the banks of the Tiber. Victor Emmanuel installed himself in the Quirinal Palace. Rome became once again, for the first time in thirteen centuries, the capital city of a united Italy.

Rome was unusual among capital cities only in that it contained the power of the Pope and a small parcel of land (Vatican City) beyond national control. This anomaly was not formally resolved until the Lateran pacts of 1929.

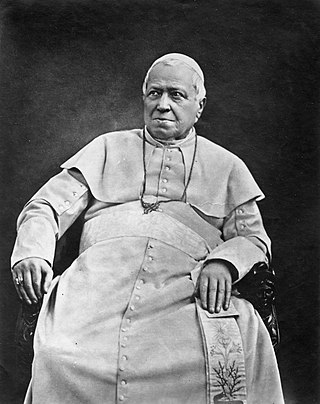

Pope Pius spent the last eight years of his long pontificate – the longest in Church history – as prisoner of the Vatican. Catholics were forbidden to vote or be voted in national elections. However, they were permitted to participate in local elections, where they achieved successes. [4] Pius himself was active during those years, by creating new diocesan seats and appointing bishops to numerous dioceses which had been unoccupied for years. Asked if he wanted his successor to follow his Italian policies, the old pontiff replied:

My successor may be inspired by my love to the Church and my wish, to do the right thing. Everything changed around me. My system and my policies had their time; I am too old to change direction. This will be the task of my successor. [5]

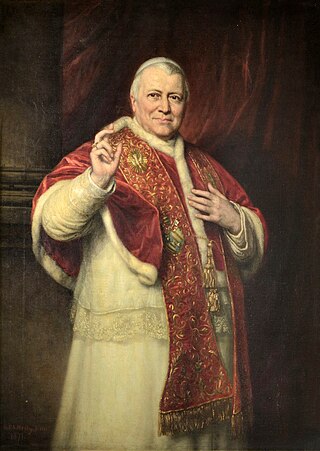

Pope Leo XIII, considered a great diplomat, managed to improve relations with Russia, Prussia, Germany, France, England and other countries. However, in light of a hostile anti-Catholic climate in Italy, he continued the policies of Pius IX towards Italy, without major modifications. [6] He had to defend the freedom of the Church against Italian persecutions and attacks in the area of education, expropriation and violation of Catholic churches, legal measures against the Church and brutal attacks, culminating in anticlerical groups attempting to throw the body of the deceased Pope Pius IX into the Tiber river on 13 July 1881. [7] The Pope even considered moving the papacy to Spain, Malta or to Trieste or Salzburg, two cities in Austria, an idea which the Austrian monarch Franz Josef I gently rejected. [8]

Paradoxically, the eclipse of papal temporal power during the 19th century was accompanied by a recovery of papal prestige. The monarchist reaction in the wake of the French Revolution and the later emergence of constitutional governments served alike, though in different ways, to sponsor that development. The reinstated monarchs of Catholic Europe saw in the papacy a conservative ally rather than a jurisdictional rival. Later, when the institution of constitutional governments broke the ties binding the clergy to the policies of royal regimes, Catholics were freed to respond to the renewed spiritual authority of the pope.

The popes of the 19th and 20th centuries exercised their spiritual authority with increasing vigor and in every aspect of religious life. By the crucial pontificate of Pope Pius IX (1846–1878), for example, papal control over worldwide Catholic missionary activity was firmly established for the first time in history.

Pope Leo XIII was head of the Catholic Church from 20 February 1878 to his death in July 1903. Living until the age of 93, he was the second-oldest-serving pope, and the third-longest-lived pope in history, before Pope Benedict XVI as Pope emeritus, and had the fourth-longest reign of any, behind those of St. Peter, Pius IX and John Paul II.

Pope Pius IX was head of the Catholic Church from 1846 to 1878, the longest verified papal reign. He was notable for convoking the First Vatican Council in 1868 and for permanently losing control of the Papal States in 1870 to the Kingdom of Italy. Thereafter, he refused to leave Vatican City, declaring himself a "prisoner of the Vatican".

The Papal States, officially the State of the Church, were a series of territories in the Italian Peninsula under the direct sovereign rule of the pope from 756 until 1870. They were among the major states of Italy from the 8th century until the unification of Italy, between 1859 and 1870.

The temporal powerof the Holy See designates the political and secular influence of the Holy See, the leading of a state by the pope of the Catholic Church, as distinguished from its spiritual and pastoral activity.

The Roman Republic was a short-lived state declared on 9 February 1849, when the government of the Papal States was temporarily replaced by a republican government due to Pope Pius IX's departure to Gaeta. The republic was led by Carlo Armellini, Giuseppe Mazzini, and Aurelio Saffi. Together they formed a triumvirate, a reflection of a form of government during the first century BC crisis of the Roman Republic.

A prisoner in the Vatican or prisoner of the Vatican described the situation of the Pope with respect to Italy during the period from the capture of Rome by the armed forces of the Kingdom of Italy on 20 September 1870 until the Lateran Treaty of 11 February 1929. Part of the process of Italian unification, the city's capture ended the millennium-old temporal rule of the popes over central Italy and allowed Rome to be designated the capital of the new nation. Although the Italians did not occupy the territories of Vatican Hill delimited by the Leonine walls and offered the creation of a city-state in the area, the Popes from Pius IX to Pius XI refused the proposal and described themselves as prisoners of the new Italian state.

The September Convention was a treaty, signed on 15 September 1864, between the Kingdom of Italy and the French Empire, under which:

The 1846 papal conclave was triggered after death of Pope Gregory XVI on 1 June 1846. Fifty of the 62 members of the College of Cardinals assembled in the Quirinal Palace, one of the papal palaces in Rome and the seat of two earlier 19th century conclaves. The conclave began on 14 June and had to elect a pope who would not only be head of the Catholic Church but also the head of state and government of the Papal States, the extensive lands around Rome and Northern Italy which the Catholic Church governed.

The 1878 papal conclave, which resulted from the death of Pope Pius IX on 7 February 1878, met from 18 to 20 February. The conclave followed the longest reign of any other pope since Saint Peter. It was the first election of a pope who would not rule the Papal States. It was the first to meet in the Apostolic Palace in the Vatican because the venue used earlier in the 19th century, the Quirinal Palace, was now the palace of the King of Italy, Umberto I.

Neo-Guelphism was a 19th-century Italian political movement, started by Vincenzo Gioberti, which wanted to unite Italy into a single kingdom with the Pope as its king. Despite little popular support, the movement raised interests among intellectuals, journalists and Catholic reformist politicians. They were also linked both to ontologism, a philosophical movement, and to rationalist-leaning theology.

The history of the papacy, the office held by the pope as head of the Catholic Church, spans from the time of Peter, to the present day. Moreover, many of the bishops of Rome in the first three centuries of the Christian era are obscure figures. Most of Peter's successors in the first three centuries following his life suffered martyrdom along with members of their flock in periods of persecution.

The Roman question was a dispute regarding the temporal power of the popes as rulers of a civil territory in the context of the Italian Risorgimento. It ended with the Lateran Pacts between King Victor Emmanuel III of Italy and Pope Pius XI in 1929.

The Capture of Rome on 20 September 1870 was the final event of the unification of Italy (Risorgimento), marking both the final defeat of the Papal States under Pope Pius IX and the unification of the Italian Peninsula under the Kingdom of Italy.

The history of Rome includes the history of the city of Rome as well as the civilisation of ancient Rome. Roman history has been influential on the modern world, especially in the history of the Catholic Church, and Roman law has influenced many modern legal systems. Roman history can be divided into the following periods:

The foreign relations between Pope Pius IX and France were characterized by the hostility of the Third Republic's anticlerical politics, as well as Napoleon III's influence over the papal states. This did not stop, however, Church life in France from flourishing during much of Pius IX's pontificate.

Foreign relations between Pope Pius IX and Italy were characterized by an extensive political and diplomatic conflict over Italian unification and the subsequent status of Rome after the victory of the liberal revolutionaries.

The theology of Pope Pius IX championed the pontiff's role as the highest teaching authority in the Church.

The Papal States under Pope Pius IX assumed a much more modern and secular character than had been seen under previous pontificates, and yet this progressive modernization was not nearly sufficient in resisting the tide of political liberalization and unification in Italy during the middle of the 19th century.

The modern history of the papacy is shaped by the two largest dispossessions of papal property in its history, stemming from the French Revolution and its spread to Europe, including Italy.

The Law of Guarantees, sometimes also called the Law of Papal Guarantees, was the name given to the law passed by the senate and chamber of the Italian parliament, 13 May, 1871, concerning the prerogatives of the Holy See, and the relations between State and Church in the Kingdom of Italy. It guaranteed sovereign prerogatives to the Roman Pontiff, who had been deprived of the territory of the papal states. The popes refused to accept the law, as it was enacted by a foreign government and could therefore be revoked at will, leaving the popes without a full claim to sovereign status. In response, the popes declared themselves prisoners of the Vatican. The ensuing Roman Question was not resolved until the Lateran Pacts of 1929.