A lagoon is a shallow body of water separated from a larger body of water by a narrow landform, such as reefs, barrier islands, barrier peninsulas, or isthmuses. Lagoons are commonly divided into coastal lagoons and atoll lagoons. They have also been identified as occurring on mixed-sand and gravel coastlines. There is an overlap between bodies of water classified as coastal lagoons and bodies of water classified as estuaries. Lagoons are common coastal features around many parts of the world.

In oceanography, geomorphology, and geoscience, a shoal is a natural submerged ridge, bank, or bar that consists of, or is covered by, sand or other unconsolidated material, and rises from the bed of a body of water close to the surface or above it, which poses a danger to navigation. Shoals are also known as sandbanks, sandbars, or gravelbars. Two or more shoals that are either separated by shared troughs or interconnected by past or present sedimentary and hydrographic processes are referred to as a shoal complex.

A spit or sandspit is a deposition bar or beach landform off coasts or lake shores. It develops in places where re-entrance occurs, such as at a cove's headlands, by the process of longshore drift by longshore currents. The drift occurs due to waves meeting the beach at an oblique angle, moving sediment down the beach in a zigzag pattern. This is complemented by longshore currents, which further transport sediment through the water alongside the beach. These currents are caused by the same waves that cause the drift.

Longshore drift from longshore current is a geological process that consists of the transportation of sediments along a coast parallel to the shoreline, which is dependent on the angle of incoming wave direction. Oblique incoming wind squeezes water along the coast, and so generates a water current which moves parallel to the coast. Longshore drift is simply the sediment moved by the longshore current. This current and sediment movement occur within the surf zone. The process is also known as littoral drift.

Barrier islands are a coastal landform, a type of dune system and sand island, where an area of sand has been formed by wave and tidal action parallel to the mainland coast. They usually occur in chains, consisting of anything from a few islands to more than a dozen. They are subject to change during storms and other action, but absorb energy and protect the coastlines and create areas of protected waters where wetlands may flourish. A barrier chain may extend for hundreds of kilometers, with islands periodically separated by tidal inlets. The largest barrier island in the world is Padre Island of Texas, United States, at 113 miles (182 km) long. Sometimes an important inlet may close permanently, transforming an island into a peninsula, thus creating a barrier peninsula, often including a beach, barrier beach. Though many are long and narrow, the length and width of barriers and overall morphology of barrier coasts are related to parameters including tidal range, wave energy, sediment supply, sea-level trends, and basement controls. The amount of vegetation on the barrier has a large impact on the height and evolution of the island.

Lake Ellesmere / Te Waihora is a broad, shallow coastal lake or waituna, in the Canterbury region of the South Island of New Zealand. It is directly to the west of Banks Peninsula, separated from the Pacific Ocean by the long, narrow, sandy Kaitorete Spit, or more correctly Kaitorete Barrier. It lies partially in extreme southeastern Selwyn District and partially in the southwestern extension of the former Banks Peninsula District, which now is a ward in the city of Christchurch. The lake holds high historical and cultural significance to the indigenous Māori population and the traditional Māori name Te Waihora, means spreading waters. It has officially had a dual English/Māori name since at least 1938.

The Selwyn River flows through the Selwyn District of Canterbury in the South Island of New Zealand.

Lake Grassmere / Kapara Te Hau is a New Zealand waituna-type lagoon in the northeastern South Island, close to Cook Strait. The lake is used for the production of salt.

Coastal geography is the study of the constantly changing region between the ocean and the land, incorporating both the physical geography and the human geography of the coast. It includes understanding coastal weathering processes, particularly wave action, sediment movement and weather, and the ways in which humans interact with the coast.

Kaitorete Spit is a long finger of land which extends along the coast of Canterbury in the South Island of New Zealand. It runs west from Banks Peninsula for 25 kilometres, and separates the shallow Lake Ellesmere / Te Waihora from the Pacific Ocean. It is technically a continuous barrier beach, though at its western end it tapers to a point less than 100 metres in width which is occasionally breached at high tide. The spit is noted for its isolation and for its pebbly beaches. At its eastern end is the small settlement of Birdlings Flat, and west of its narrowest point is the settlement of Taumutu.

Cuspate forelands, also known as cuspate barriers or nesses in Britain, are geographical features found on coastlines and lakeshores that are created primarily by longshore drift. Formed by accretion and progradation of sand and shingle, they extend outwards from the shoreline in a triangular shape.

Beach evolution occurs at the shoreline where sea, lake or river water is eroding the land. Beaches exist where sand accumulated from centuries-old, recurrent processes that erode rocky and sedimentary material into sand deposits. River deltas deposit silt from upriver, accreting at the river's outlet to extend lake or ocean shorelines. Catastrophic events such as tsunamis, hurricanes, and storm surges accelerate beach erosion.

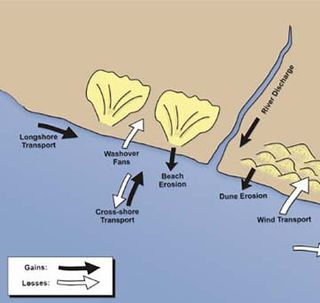

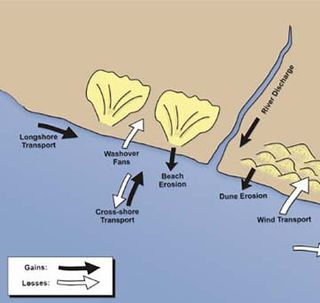

Sedimentary budgets are a coastal management tool used to analyze and describe the different sediment inputs (sources) and outputs (sinks) on the coasts, which is used to predict morphological change in any particular coastline over time. Within a coastal environment the rate of change of sediment is dependent on the amount of sediment brought into the system versus the amount of sediment that leaves the system. These inputs and outputs of sediment then equate to the total balance of the system and more than often reflect the amounts of erosion or accretion affecting the morphology of the coast.

Washdyke Lagoon is a brackish shallow coastal lagoon approximately 1 kilometre (0.62 mi) north of Timaru, South Canterbury, New Zealand. The lagoon has drastically reduced in size since 1881 when it was approximately 253 hectares, now it is less than 48 hectares (0.48 km2) in area. It is enclosed by a barrier beach that is 3 kilometres (1.9 mi) long and 3 metres (9.8 ft) above high tide at its largest point. The reduced lagoon size is due to the construction of the Timaru Port breakwater which is preventing coarse sediments from reaching and replenishing Washdyke Barrier. This is important as the lagoon and the surrounding 250 hectares are classified as a wildlife refuge and it demonstrates the role human structures have on coastline evolution.

Lake Forsyth is a lake on the south-western side of Banks Peninsula in the Canterbury region of New Zealand, near the eastern end of the much larger Lake Ellesmere / Te Waihora. State Highway 75 to Akaroa and the Little River Rail Trail run along the north-western side of the lake.

The Estuary of the Heathcote and Avon Rivers / Ihutai is the largest semi-enclosed shallow estuary in Canterbury and remains one of New Zealand's most important coastal wetlands. It is well known as an internationally important habitat for migratory birds, and it is an important recreational playground and educational resource. It was once highly valued for mahinga kai.

The Canterbury Bight is a large bight on the eastern side of New Zealand's South Island. The bight runs for approximately 135 kilometres (84 mi) from the southern end of Banks Peninsula to the settlement of Timaru and faces southeast, exposing it to high-energy storm waves originating in the Pacific Ocean. The bight is known for rough conditions as a result, with wave heights of over 2 metres (6.6 ft) common. Much of the bight's geography is shaped by this high-energy environment interacting with multiple large rivers which enter the Pacific in the bight, such as the Rakaia, Ashburton / Hakatere, and Rangitata Rivers. Sediment from these rivers, predominantly Greywacke, is deposited along the coast and extends up to 50 kilometres (31 mi) out to sea from the current shoreline. Multiple hapua, or river-mouth lagoons, can be found along the length of the bight where waves have deposited sufficient sediment to form a barrier across a river mouth, including most notably Lake Ellesmere / Te Waihora and Washdyke Lagoon

The Waituna Lagoon is on the southern coastline of the South Island of New Zealand. It forms part of the Awarua Wetland, a Ramsar site that was established in 1976. It gives it name to waituna, a type of ephemeral coastal lake.

A hapua is a river-mouth lagoon on a mixed sand and gravel (MSG) beach, formed at the river-coast interface where a typically braided, although sometimes meandering, river interacts with a coastal environment that is significantly affected by longshore drift. The lagoons which form on the MSG coastlines are common on the east coast of the South Island of New Zealand and have long been referred to as hapua by Māori people. This classification differentiates hapua from similar lagoons located on the New Zealand coast termed waituna.

Coopers Lagoon / Muriwai is a small coastal waituna-type lagoon in the Canterbury region of New Zealand, located approximately half way between the mouth of the Rakaia River and the outlet of the much larger Lake Ellesmere / Te Waihora. While the present-day lagoon is separated from the nearby Canterbury Bight by approximately 100 metres (330 ft), the water of the lagoon is considered brackish and early survey maps show that, until recently, the lagoon was connected to the ocean by a small channel. The lagoon, along with the surrounding wetlands, has historically been an important mahinga kai for local Māori.