A cave or cavern is a natural void in the ground, specifically a space large enough for a human to enter. Caves often form by the weathering of rock and often extend deep underground. The word cave can refer to smaller openings such as sea caves, rock shelters, and grottos, that extend a relatively short distance into the rock and they are called exogene caves. Caves which extend further underground than the opening is wide are called endogene caves.

Karst is a topography formed from the dissolution of soluble carbonate rocks such as limestone, dolomite, and gypsum. It is characterized by features like poljes above and drainage systems with sinkholes and caves underground. More weathering-resistant rocks, such as quartzite, can also occur, given the right conditions.

A natural arch, natural bridge, or rock arch is a natural landform where an arch has formed with an opening underneath. Natural arches commonly form where inland cliffs, coastal cliffs, fins or stacks are subject to erosion from the sea, rivers or weathering.

A sinkhole is a depression or hole in the ground caused by some form of collapse of the surface layer. The term is sometimes used to refer to doline, enclosed depressions that are also known as shakeholes, and to openings where surface water enters into underground passages known as ponor, swallow hole or swallet. A cenote is a type of sinkhole that exposes groundwater underneath. Sink and stream sink are more general terms for sites that drain surface water, possibly by infiltration into sediment or crumbled rock.

A stack or sea stack is a geological landform consisting of a steep and often vertical column or columns of rock in the sea near a coast, formed by wave erosion. Stacks are formed over time by wind and water, processes of coastal geomorphology. They are formed when part of a headland is eroded by hydraulic action, which is the force of the sea or water crashing against the rock. The force of the water weakens cracks in the headland, causing them to later collapse, forming free-standing stacks and even a small island. Without the constant presence of water, stacks also form when a natural arch collapses under gravity, due to sub-aerial processes like wind erosion. Erosion causes the arch to collapse, leaving the pillar of hard rock standing away from the coast—the stack. Eventually, erosion will cause the stack to collapse, leaving a stump. Stacks can provide important nesting locations for seabirds, and many are popular for rock climbing.

Landforms are categorized by characteristic physical attributes such as their creating process, shape, elevation, slope, orientation, rock exposure, and soil type.

Anacapa Island is a small volcanic island located about 11 miles off Port Hueneme in Ventura County, California. The island is composed of a series of narrow islets 6 mi (10 km) long, oriented generally east–west and 5 mi (8 km) east of Santa Cruz Island. The three main islets, East, Middle and West Anacapa, have precipitous cliffs, dropping off steeply into the sea.

Channel Islands National Park consists of five of the eight Channel Islands off the Pacific coast of the U.S. state of California. Although the islands are close to the shore of the densely populated state, they have been relatively undeveloped. The park covers 249,561 acres (100,994 ha), of which 79,019 acres (31,978 ha) are federal land.

Deposition is the geological process in which sediments, soil and rocks are added to a landform or landmass. Wind, ice, water, and gravity transport previously weathered surface material, which, at the loss of enough kinetic energy in the fluid, is deposited, building up layers of sediment.

The Poor Knights Islands are a group of islands off the east coast of the Northland Region of the North Island of New Zealand. They lie 50 kilometres (31 mi) to the northeast of Whangārei, and 22 kilometres (14 mi) offshore halfway between Bream Head and Cape Brett. Uninhabited since the 1820s, they are a nature reserve and popular underwater diving spot, with boat tours typically departing from Tutukaka. The Poor Knights Islands Marine Reserve surrounds the island.

Paparoa National Park is on the west coast of the South Island of New Zealand.

In geology, a blowhole or marine geyser is formed as sea caves grow landward and upward into vertical shafts and expose themselves toward the surface, which can result in hydraulic compression of seawater that is released through a port from the top of the blowhole. The geometry of the cave and blowhole along with tide levels and swell conditions determine the height of the spray.

A blue hole is a large marine cavern or sinkhole, which is open to the surface and has developed in a bank or island composed of a carbonate bedrock. Blue holes typically contain tidally influenced water of fresh, marine, or mixed chemistry. They extend below sea level for most of their depth and may provide access to submerged cave passages. Well-known examples are the Dragon Hole and, in the Caribbean, the Great Blue Hole and Dean's Blue Hole.

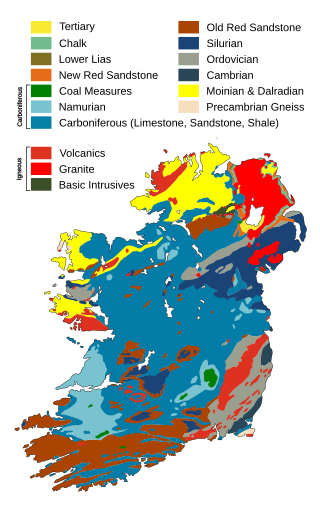

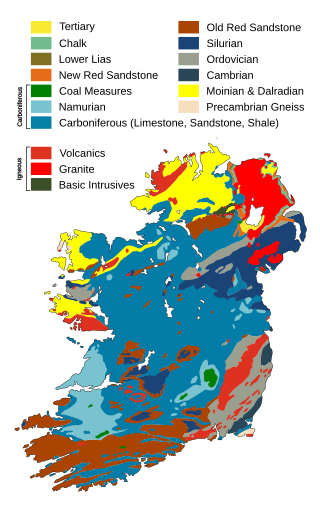

The geology of Ireland consists of the study of the rock formations on the island of Ireland. It includes rocks from every age from Proterozoic to Holocene and a large variety of different rock types is represented. The basalt columns of the Giant's Causeway together with geologically significant sections of the adjacent coast have been declared a World Heritage Site. The geological detail follows the major events in Ireland's past based on the geological timescale.

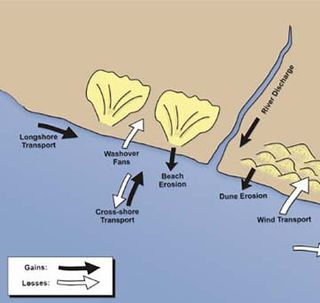

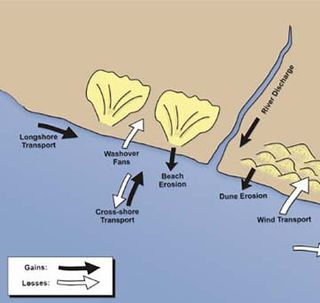

Beach evolution occurs at the shoreline where sea, lake or river water is eroding the land. Beaches exist where sand accumulated from centuries-old, recurrent processes that erode rocky and sedimentary material into sand deposits. River deltas deposit silt from upriver, accreting at the river's outlet to extend lake or ocean shorelines. Catastrophic events such as tsunamis, hurricanes, and storm surges accelerate beach erosion.

Sedimentary budgets are a coastal management tool used to analyze and describe the different sediment inputs (sources) and outputs (sinks) on the coasts, which is used to predict morphological change in any particular coastline over time. Within a coastal environment the rate of change of sediment is dependent on the amount of sediment brought into the system versus the amount of sediment that leaves the system. These inputs and outputs of sediment then equate to the total balance of the system and more than often reflect the amounts of erosion or accretion affecting the morphology of the coast.

The Tantanoola Caves Conservation Park is a 14-hectare (35-acre) protected area near Tantanoola in the Limestone Coast tourism region in the south-east of South Australia. The conservation park preserves two main caves; the wheelchair accessible Tantanoola Cave which is developed as a show cave and Lake Cave which is a restricted access cave used by the Department for Environment and Water scientists as a reference site for other karst features in the region. Visitors can explore the information centre and learn about the caves during a guided tour.

The Pancake Rocks and Blowholes are a coastal rock formation at Punakaiki on the West Coast of the South Island of New Zealand. They are a popular visitor attraction.

An anchialine system is a landlocked body of water with a subterranean connection to the ocean. Depending on its formation, these systems can exist in one of two primary forms: pools or caves. The primary differentiating characteristics between pools and caves is the availability of light; cave systems are generally aphotic while pools are euphotic. The difference in light availability has a large influence on the biology of a given system. Anchialine systems are a feature of coastal aquifers which are density stratified, with water near the surface being fresh or brackish, and saline water intruding from the coast at depth. Depending on the site, it is sometimes possible to access the deeper saline water directly in the anchialine pool, or sometimes it may be accessible by cave diving.