The 1200s began on January 1, 1200, and ended on December 31, 1209.

Year 1187 (MCLXXXVII) was a common year starting on Thursday of the Julian calendar.

The 1180s was a decade of the Julian Calendar which began on January 1, 1180, and ended on December 31, 1189.

The 1190s was a decade of the Julian calendar which began on January 1, 1190, and ended on December 31, 1199.

Year 1224 (MCCXXIV) was a leap year starting on Monday of the Julian calendar.

Year 1189 (MCLXXXIX) was a common year starting on Sunday of the Julian calendar. In English law, 1189 - specifically the beginning of the reign of Richard I - is considered the end of time immemorial.

Year 1205 (MCCV) was a common year starting on Saturday of the Julian calendar.

1200 (MCC) was a leap year starting on Saturday of the Julian calendar, the 1200th year of the Common Era (CE) and Anno Domini (AD) designations, the 200th year of the 2nd millennium, the 100th and last year of the 12th century, and the 1st year of the 1200s decade. As of the start of 1200, the Gregorian calendar was 7 days ahead of the Julian calendar, which was the dominant calendar of the time.

Year 1180 (MCLXXX) was a leap year starting on Tuesday of the Julian calendar.

Year 1290 (MCCXC) was a common year starting on Sunday of the Julian calendar.

Year 1203 (MCCIII) was a common year starting on Wednesday of the Julian calendar. It was also the first year to have all digits different from each other since 1098.

Year 1201 (MCCI) was a common year starting on Monday of the Julian calendar.

Year 1191 (MCXCI) was a common year starting on Tuesday of the Julian calendar.

Year 1289 (MCCLXXXIX) was a common year starting on Saturday of the Julian calendar.

The Fourth Crusade (1202–1204) was a Latin Christian armed expedition called by Pope Innocent III. The stated intent of the expedition was to recapture the Muslim-controlled city of Jerusalem, by first defeating the powerful Egyptian Ayyubid Sultanate. However, a sequence of economic and political events culminated in the Crusader army's 1202 siege of Zara and the 1204 sack of Constantinople, rather than the conquest of Egypt as originally planned. This led to the Partitio terrarum imperii Romaniae or the partition of the Byzantine Empire by the Crusaders and their Venetian allies leading to a period known as Frankokratia, or "Rule of the Franks" in Greek.

Alexios IV Angelos, Latinized as Alexius IV Angelus, was Byzantine Emperor from August 1203 to January 1204. He was the son of Emperor Isaac II Angelos and his first wife, an unknown Palaiologina, who became a nun with the name Irene. His paternal uncle was his predecessor Emperor Alexios III Angelos. He is widely regarded as one of the worst Byzantine emperors for calling upon the Fourth Crusade to help him gain power, which ultimately led to the sack of Constantinople.

David C. Nicolle is a British historian specialising in the military history of the Middle Ages, with a particular interest in the Middle East.

The Byzantine Empire was ruled by emperors of the Angelos dynasty between 1185 and 1204 AD. The Angeloi rose to the throne following the deposition of Andronikos I Komnenos, the last male-line Komnenos to rise to the throne. The Angeloi were female-line descendants of the previous dynasty. While in power, the Angeloi were unable to stop the invasions of the Turks by the Sultanate of Rum, the uprising and resurrection of the Bulgarian Empire, and the loss of the Dalmatian coast and much of the Balkan areas won by Manuel I Komnenos to the Kingdom of Hungary.

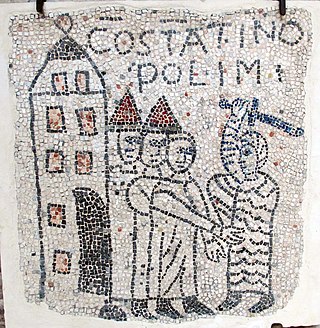

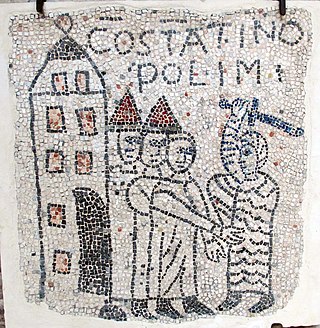

The sack of Constantinople occurred in April 1204 and marked the culmination of the Fourth Crusade. Crusaders sacked and destroyed most of Constantinople, the capital of the Byzantine Empire. After the capture of the city, the Latin Empire was established and Baldwin of Flanders crowned as Emperor Baldwin I of Constantinople in Hagia Sophia.

The siege of Constantinople in 1203 was a crucial episode of the Fourth Crusade, marking the beginning of a series of events that would ultimately lead to the fall of the Byzantine capital. The crusaders, diverted from their original mission to reclaim Jerusalem, found themselves in Constantinople, in support of the deposed emperor Isaac II Angelos and his son Alexios IV Angelos. The besieging forces, primarily composed of Western European knights faced initial setbacks, but their determination and advanced siege weaponry played a pivotal role in pressuring the Byzantine defenders.