The history of Atlanta dates back to 1836, when Georgia decided to build a railroad to the U.S. Midwest and a location was chosen to be the line's terminus. The stake marking the founding of "Terminus" was driven into the ground in 1837. In 1839, homes and a store were built there and the settlement grew. Between 1845 and 1854, rail lines arrived from four different directions, and the rapidly growing town quickly became the rail hub for the entire Southern United States. During the American Civil War, Atlanta, as a distribution hub, became the target of a major Union campaign, and in 1864, Union William Sherman's troops set on fire and destroyed the city's assets and buildings, save churches and hospitals. After the war, the population grew rapidly, as did manufacturing, while the city retained its role as a rail hub. Coca-Cola was launched here in 1886 and grew into an Atlanta-based world empire. Electric streetcars arrived in 1889, and the city added new "streetcar suburbs".

The city of Atlanta, Georgia is made up of 243 neighborhoods officially defined by the city. These neighborhoods are a mix of traditional neighborhoods, subdivisions, or groups of subdivisions. The neighborhoods are grouped by the city planning department into 25 neighborhood planning units (NPUs). These NPUs are "citizen advisory councils that make recommendations to the Mayor and City Council on zoning, land use, and other planning issues". There are a variety of other widely recognized named areas within the city. Some are officially designated, while others are more informal.

Ivan Earnest Allen Jr., was an American businessman who served two terms as the 52nd mayor of Atlanta, during the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s.

Cascade Heights is an affluent neighborhood in southwest Atlanta. It is bisected by Cascade Road, which was known as the Sandtown Road in the nineteenth century. The road follows the path of the ancient Sandtown Trail which ran from Stone Mountain to the Creek village of Sandtown on the Chattahoochee River and from there on into Alabama. Ironically, the name lived on even after the Indians were expelled in the 1830s.

Facilities and services such as housing, healthcare, education, employment, and transportation have been systematically separated in the United States based on racial categorizations. Segregation was the legally or socially enforced separation of African Americans from whites, as well as the separation of other ethnic minorities from majority and mainstream communities. While mainly referring to the physical separation and provision of separate facilities, it can also refer to other manifestations such as prohibitions against interracial marriage, and the separation of roles within an institution. The U.S. Armed Forces were formally segregated until 1948, as black units were separated from white units but were still typically led by white officers.

The 1906 Atlanta Race Massacre, also known as the 1906 Atlanta Race Riot, was an episode of mass racial violence against African Americans in the United States in September 1906. Violent attacks by armed mobs of White Americans against African Americans in Atlanta, Georgia, began after newspapers, on the evening of September 22, 1906, published several unsubstantiated and luridly detailed reports of the alleged rapes of 4 local women by black men. The violence lasted through September 24, 1906. The events were reported by newspapers around the world, including the French Le Petit Journal which described the "lynchings in the USA" and the "massacre of Negroes in Atlanta," the Scottish Aberdeen Press & Journal under the headline "Race Riots in Georgia," and the London Evening Standard under the headlines "Anti-Negro Riots" and "Outrages in Georgia." The final death toll of the conflict is unknown and disputed, but officially at least 25 African Americans and two whites died. Unofficial reports ranged from 10–100 black Americans killed during the massacre. According to the Atlanta History Center, some black Americans were hanged from lampposts; others were shot, beaten or stabbed to death. They were pulled from street cars and attacked on the street; white mobs invaded black neighborhoods, destroying homes and businesses.

Lugenia Burns Hope, was a social reformer whose Neighborhood Union and other community service organizations improved the quality of life for African Americans in Atlanta, Georgia, and served as a model for the future Civil Rights Movement.

African-American neighborhoods or black neighborhoods are types of ethnic enclaves found in many cities in the United States. Generally, an African American neighborhood is one where the majority of the people who live there are African American. Some of the earliest African-American neighborhoods were in New Orleans, Mobile, Atlanta, and other cities throughout the American South, as well as in New York City. In 1830, there were 14,000 "Free negroes" living in New York City.

Washington Park is a historically black neighborhood in northwest Atlanta encompassing historic residential, commercial, and community landmark buildings. It is situated two miles (3 km) west of the central business district of Atlanta. The combination of gridiron and curvilinear streets is a result of the neighborhood having been developed from four separate subdivision plats. One of these plats created Atlanta's first planned black neighborhood, while the other three were abandoned by white developers and adopted by Heman Perry, an early 20th-century black developer. Although Perry did not receive a formal education past the seventh grade, in 1913 he founded one of the largest black-owned companies in the United States, the Standard Life Insurance Company of Atlanta.

The New Great Migration is the demographic change from 1970 to the present, which is a reversal of the previous 60-year trend of black migration within the United States.

Residential segregation is the physical separation of two or more groups into different neighborhoods—a form of segregation that "sorts population groups into various neighborhood contexts and shapes the living environment at the neighborhood level". While it has traditionally been associated with racial segregation, it generally refers to the separation of populations based on some criteria.

The Atlanta Student Movement was formed in February 1960 in Atlanta by students of the campuses Atlanta University Center (AUC). It was led by the Committee on the Appeal for Human Rights (COAHR) and was part of the Civil Rights Movement.

Black Atlantans form a major population group in the Atlanta metropolitan area, encompassing both those of African-American ancestry as well as those of recent Caribbean or African origin. Atlanta has long been known as a center of black entrepreneurship, higher education, political power and culture; a cradle of the Civil Rights Movement.

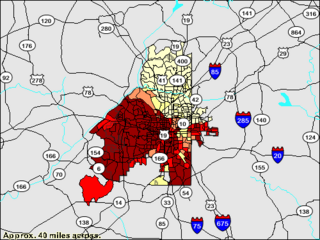

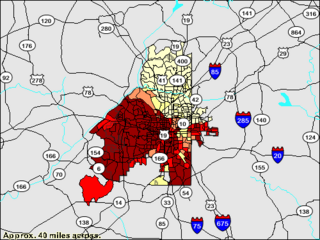

Racial segregation in Atlanta has known many phases after the freeing of the slaves in 1865: a period of relative integration of businesses and residences; Jim Crow laws and official residential and de facto business segregation after the Atlanta Race Riot of 1906; blockbusting and black residential expansion starting in the 1950s; and gradual integration from the late 1960s onwards. A 2015 study conducted by Nate Silver of fivethirtyeight.com, found that Atlanta was the second most segregated city in the U.S. and the most segregated in the South.

Austen Thomas Walden, also known as A. T. Walden was an American lawyer and civil rights leader. In 1964, he was appointed by Ivan Allen Jr. as a municipal judge, the first black judge to be appointed in the state of Georgia since Reconstruction.

In the United States, school integration is the process of ending race-based segregation within American public and private schools. Racial segregation in schools existed throughout most of American history and remains an issue in contemporary education. During the Civil Rights Movement school integration became a priority, but since then de facto segregation has again become prevalent.

The English Avenue School is an historic school building in Atlanta, Georgia, United States. Located in the city's English Avenue neighborhood, the school was built in 1910 and operated until 1995. It was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2020.

The Atlanta sit-ins were a series of sit-ins that took place in Atlanta, Georgia, United States. Occurring during the sit-in movement of the larger civil rights movement, the sit-ins were organized by the Committee on Appeal for Human Rights, which consisted of students from the Atlanta University Center. The sit-ins were inspired by the Greensboro sit-ins, which had started a month earlier in Greensboro, North Carolina with the goal of desegregating the lunch counters in the city. The Atlanta protests lasted for almost a year before an agreement was made to desegregate the lunch counters in the city.

The University of Georgia desegregation riot was an incident of mob violence by proponents of racial segregation on January 11, 1961. The riot was caused by segregationists' protest over the desegregation of the University of Georgia (UGA) in Athens, Georgia following the enrollment of Hamilton E. Holmes and Charlayne Hunter, two African American students. The two had been admitted to the school several days earlier following a lengthy application process that led to a court order mandating that the university accept them. On January 11, several days after the two had registered, a group of approximately 1,000 people conducted a riot outside of Hunter's dormitory. In the aftermath, Holmes and Hunter were suspended by the university's dean, though this suspension was later overturned by a court order. Several rioters were arrested, with several students placed on disciplinary probation, but no one was charged with inciting the riot. In an investigation conducted by the Federal Bureau of Investigation, it was revealed that some of the riot organizers were in contact with elected state officials who approved of the riot and assured them of immunity for conducting the riot.

The Ministers' Manifesto refers to a series of manifestos written and endorsed by religious leaders in Atlanta, Georgia, United States, during the 1950s. The first manifesto was published in 1957 and was followed by another the following year. The manifestos were published during the civil rights movement amidst a national process of school integration that had begun several years earlier. Many white conservative politicians in the Southern United States embraced a policy of massive resistance to maintain school segregation. However, the 80 clergy members that signed the manifesto, which was published in Atlanta's newspapers on November 3, 1957, offered several key tenets that they said should guide any debate on school integration, including a commitment to keeping public schools open, communication between both white and African American leaders, and obedience to the law. In October 1958, following the Hebrew Benevolent Congregation Temple bombing in Atlanta, 311 clergy members signed another manifesto that reiterated the points made in the previous manifesto and called on the governor of Georgia to create a citizens' commission to help with the eventual school integration process in Atlanta. In August 1961, the city initiated the integration of its public schools.