The Turkic languages are a language family of more than 35 documented languages, spoken by the Turkic peoples of Eurasia from Eastern Europe and Southern Europe to Central Asia, East Asia, North Asia (Siberia), and West Asia. The Turkic languages originated in a region of East Asia spanning from Mongolia to Northwest China, where Proto-Turkic is thought to have been spoken, from where they expanded to Central Asia and farther west during the first millennium. They are characterized as a dialect continuum.

The Bulgars were Turkic semi-nomadic warrior tribes that flourished in the Pontic–Caspian steppe and the Volga region between the 5th and 7th centuries. They became known as nomadic equestrians in the Volga-Ural region, but some researchers trace Bulgar ethnic roots to Central Asia.

The Sabirs were a nomadic Turkic equestrian people who lived in the north of the Caucasus beginning in the late-5th–7th century, on the eastern shores of the Black Sea, in the Kuban area, and possibly came from Western Siberia. They were skilled in warfare, used siege machinery, had a large army and were boat-builders. They were also referred to as Huns, a title applied to various Eurasian nomadic tribes in the Pontic-Caspian Steppe during late antiquity. Sabirs led incursions into Transcaucasia in the late-400s/early-500s, but quickly began serving as soldiers and mercenaries during the Byzantine–Sasanian Wars on both sides. Their alliance with the Byzantines laid the basis for the later Khazar-Byzantine alliance.

Volga Bulgaria or Volga–Kama Bulgaria was a historical Bulgar state that existed between the 9th and 13th centuries around the confluence of the Volga and Kama River, in what is now European Russia. Volga Bulgaria was a multi-ethnic state with large numbers of Bulgars, Finno-Ugrians, Varangians, and East Slavs. Its strategic position allowed it to create a local trade monopoly with Norse, Cumans, and Pannonian Avars.

Bulgar is an extinct Oghur Turkic language spoken by the Bulgars.

Chuvash is a Turkic language spoken in European Russia, primarily in the Chuvash Republic and adjacent areas. It is the only surviving member of the Oghur branch of Turkic languages, one of the two principal branches of the Turkic family.

The Besermyan, Biserman, Besermans or Besermens are a numerically small Permian people in Russia.

The Onoghurs, Onoğurs, or Oğurs were a group of Turkic nomadic equestrians who flourished in the Pontic–Caspian steppe and the Volga region between 5th and 7th century, and spoke an Oghuric language.

The Mongol invasion of Volga Bulgaria lasted from 1223 to 1236. The Bulgar state, centered in lower Volga and Kama, was the center of the fur trade in Eurasia throughout most of its history. Before the Mongol conquest, Russians of Novgorod and Vladimir repeatedly looted and attacked the area, thereby weakening the Bulgar state's economy and military power. The latter ambushed the Mongols in the later 1223 or in 1224. Several clashes occurred between 1229–1234, and the Mongol Empire conquered the Bulgars in 1236.

Khazar, also known as Khazaric, was a Turkic dialect group spoken by the Khazars, a group of semi-nomadic Turkic peoples originating from Central Asia. There are few written records of the language and its features and characteristics are unknown. It is believed to have gradually become extinct by the 13th century AD as its speakers assimilated into neighboring Turkic-speaking populations.

The territory of Tatarstan, a republic of the Russian Federation, was inhabited by different groups during the prehistoric period. The state of Volga Bulgaria grew during the Middle Ages and for a time was subject to the Khazars. The Volga Bulgars became Muslim and incorporated various Turkic peoples to form the modern Volga Tatar ethnic group.

Esegels were an Oghur Turkic dynastic tribe in the Middle Ages who joined and would be assimilated into the Volga Bulgars.

The Volga Tatars or simply Tatars, and occasionally by the historical Turko-Tatars, are a Kipchak-Bulgar Turkic ethnic group native to the Volga-Ural region of western Russia. They are subdivided into various subgroups. Volga Tatars are the second-largest ethnic group in Russia after ethnic Russians. Most of them live in the republics of Tatarstan and Bashkortostan. Their native language is Tatar, a language of the Turkic language family. The predominant religion is Sunni Islam, followed by Orthodox Christianity.

Proto-Turkic is the linguistic reconstruction of the common ancestor of the Turkic languages that was spoken by the Proto-Turks before their divergence into the various Turkic peoples. Proto-Turkic separated into Oghur (western) and Common Turkic (eastern) branches. Candidates for the proto-Turkic homeland range from western Central Asia to Manchuria, with most scholars agreeing that it lay in the eastern part of the Central Asian steppe, while one author has postulated that Proto-Turkic originated 2,500 years ago in East Asia.

The Oghuric, Onoguric or Oguric languages are a branch of the Turkic language family. The only extant member of the group is the Chuvash language. The first to branch off from the Turkic family, the Oghuric languages show significant divergence from other Turkic languages, which all share a later common ancestor. Languages from this family were spoken in some nomadic tribal confederations, such as those of the Onogurs or Ogurs, Bulgars and Khazars.

The history of Chuvashia spans from the region's earliest attested habitation by Finno-Ugric peoples to its incorporation into the Russian Empire and its successor states.

Old Great Bulgaria, also often known by the Latin names Magna Bulgaria and Patria Onoguria, was a 7th-century Turkic nomadic empire formed by the Onogur-Bulgars on the western Pontic–Caspian steppe. Great Bulgaria was originally centered between the Dniester and lower Volga.

The Mishar Tatars, previously known as the Meshcheryaki (мещеряки), are the second largest subgroup of the Volga Tatars, after the Kazan Tatars. Traditionally, they have inhabited the middle and western side of Volga, including the nowadays Mordovia, Tatarstan, Bashkortostan, Ryazan, Penza, Ulyanovsk, Orenburg, Nizhny Novgorod and Samara regions of Russia. Many have since relocated to Moscow. Mishars also comprise the majority of Finnish Tatars and Tatars living in other Nordic and Baltic countries.

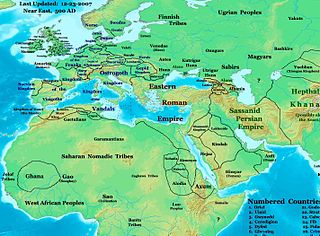

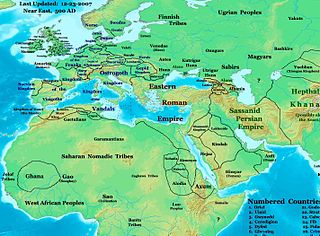

This article summarizes the History of the western steppe, which is the western third of the Eurasian steppe, that is, the grasslands of Ukraine and southern Russia. It is intended as a summary and an index to the more-detailed linked articles. It is a companion to History of the central steppe and History of the eastern steppe. All dates are approximate since there are few exact starting and ending dates. This summary article does not list the uncertainties, which are many. For these, see the linked articles.