In physics, Kaluza–Klein theory is a classical unified field theory of gravitation and electromagnetism built around the idea of a fifth dimension beyond the common 4D of space and time and considered an important precursor to string theory. In their setup, the vacuum has the usual 3 dimensions of space and one dimension of time but with another microscopic extra spatial dimension in the shape of a tiny circle. Gunnar Nordström had an earlier, similar idea. But in that case, a fifth component was added to the electromagnetic vector potential, representing the Newtonian gravitational potential, and writing the Maxwell equations in five dimensions.

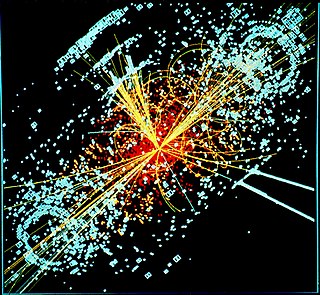

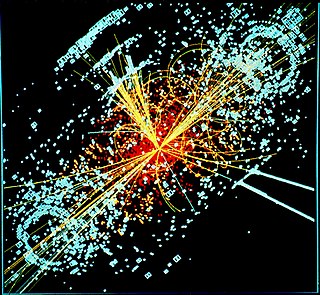

In particle physics, the Dirac equation is a relativistic wave equation derived by British physicist Paul Dirac in 1928. In its free form, or including electromagnetic interactions, it describes all spin-1/2 massive particles, called "Dirac particles", such as electrons and quarks for which parity is a symmetry. It is consistent with both the principles of quantum mechanics and the theory of special relativity, and was the first theory to account fully for special relativity in the context of quantum mechanics. It was validated by accounting for the fine structure of the hydrogen spectrum in a completely rigorous way. It has become vital in the building of the Standard Model.

The stress–energy tensor, sometimes called the stress–energy–momentum tensor or the energy–momentum tensor, is a tensor physical quantity that describes the density and flux of energy and momentum in spacetime, generalizing the stress tensor of Newtonian physics. It is an attribute of matter, radiation, and non-gravitational force fields. This density and flux of energy and momentum are the sources of the gravitational field in the Einstein field equations of general relativity, just as mass density is the source of such a field in Newtonian gravity.

In special relativity, four-momentum (also called momentum–energy or momenergy) is the generalization of the classical three-dimensional momentum to four-dimensional spacetime. Momentum is a vector in three dimensions; similarly four-momentum is a four-vector in spacetime. The contravariant four-momentum of a particle with relativistic energy E and three-momentum p = (px, py, pz) = γmv, where v is the particle's three-velocity and γ the Lorentz factor, is

In special relativity, a four-vector is an object with four components, which transform in a specific way under Lorentz transformations. Specifically, a four-vector is an element of a four-dimensional vector space considered as a representation space of the standard representation of the Lorentz group, the representation. It differs from a Euclidean vector in how its magnitude is determined. The transformations that preserve this magnitude are the Lorentz transformations, which include spatial rotations and boosts.

Linear elasticity is a mathematical model as to how solid objects deform and become internally stressed by prescribed loading conditions. It is a simplification of the more general nonlinear theory of elasticity and a branch of continuum mechanics.

In physics, Ginzburg–Landau theory, often called Landau–Ginzburg theory, named after Vitaly Ginzburg and Lev Landau, is a mathematical physical theory used to describe superconductivity. In its initial form, it was postulated as a phenomenological model which could describe type-I superconductors without examining their microscopic properties. One GL-type superconductor is the famous YBCO, and generally all cuprates.

In physics, the Hamilton–Jacobi equation, named after William Rowan Hamilton and Carl Gustav Jacob Jacobi, is an alternative formulation of classical mechanics, equivalent to other formulations such as Newton's laws of motion, Lagrangian mechanics and Hamiltonian mechanics.

In classical electromagnetism, magnetic vector potential is the vector quantity defined so that its curl is equal to the magnetic field: . Together with the electric potential φ, the magnetic vector potential can be used to specify the electric field E as well. Therefore, many equations of electromagnetism can be written either in terms of the fields E and B, or equivalently in terms of the potentials φ and A. In more advanced theories such as quantum mechanics, most equations use potentials rather than fields.

In differential geometry, the four-gradient is the four-vector analogue of the gradient from vector calculus.

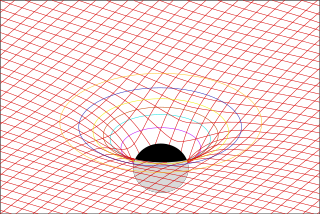

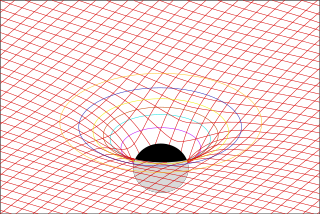

When studying and formulating Albert Einstein's theory of general relativity, various mathematical structures and techniques are utilized. The main tools used in this geometrical theory of gravitation are tensor fields defined on a Lorentzian manifold representing spacetime. This article is a general description of the mathematics of general relativity.

In electromagnetism, the electromagnetic tensor or electromagnetic field tensor is a mathematical object that describes the electromagnetic field in spacetime. The field tensor was first used after the four-dimensional tensor formulation of special relativity was introduced by Hermann Minkowski. The tensor allows related physical laws to be written concisely, and allows for the quantization of the electromagnetic field by the Lagrangian formulation described below.

A theoretical motivation for general relativity, including the motivation for the geodesic equation and the Einstein field equation, can be obtained from special relativity by examining the dynamics of particles in circular orbits about the Earth. A key advantage in examining circular orbits is that it is possible to know the solution of the Einstein Field Equation a priori. This provides a means to inform and verify the formalism.

In relativistic physics, the electromagnetic stress–energy tensor is the contribution to the stress–energy tensor due to the electromagnetic field. The stress–energy tensor describes the flow of energy and momentum in spacetime. The electromagnetic stress–energy tensor contains the negative of the classical Maxwell stress tensor that governs the electromagnetic interactions.

The covariant formulation of classical electromagnetism refers to ways of writing the laws of classical electromagnetism in a form that is manifestly invariant under Lorentz transformations, in the formalism of special relativity using rectilinear inertial coordinate systems. These expressions both make it simple to prove that the laws of classical electromagnetism take the same form in any inertial coordinate system, and also provide a way to translate the fields and forces from one frame to another. However, this is not as general as Maxwell's equations in curved spacetime or non-rectilinear coordinate systems.

In physics, Maxwell's equations in curved spacetime govern the dynamics of the electromagnetic field in curved spacetime or where one uses an arbitrary coordinate system. These equations can be viewed as a generalization of the vacuum Maxwell's equations which are normally formulated in the local coordinates of flat spacetime. But because general relativity dictates that the presence of electromagnetic fields induce curvature in spacetime, Maxwell's equations in flat spacetime should be viewed as a convenient approximation.

There are various mathematical descriptions of the electromagnetic field that are used in the study of electromagnetism, one of the four fundamental interactions of nature. In this article, several approaches are discussed, although the equations are in terms of electric and magnetic fields, potentials, and charges with currents, generally speaking.

The theory of special relativity plays an important role in the modern theory of classical electromagnetism. It gives formulas for how electromagnetic objects, in particular the electric and magnetic fields, are altered under a Lorentz transformation from one inertial frame of reference to another. It sheds light on the relationship between electricity and magnetism, showing that frame of reference determines if an observation follows electric or magnetic laws. It motivates a compact and convenient notation for the laws of electromagnetism, namely the "manifestly covariant" tensor form.

In theoretical physics, relativistic Lagrangian mechanics is Lagrangian mechanics applied in the context of special relativity and general relativity.

Lagrangian field theory is a formalism in classical field theory. It is the field-theoretic analogue of Lagrangian mechanics. Lagrangian mechanics is used to analyze the motion of a system of discrete particles each with a finite number of degrees of freedom. Lagrangian field theory applies to continua and fields, which have an infinite number of degrees of freedom.