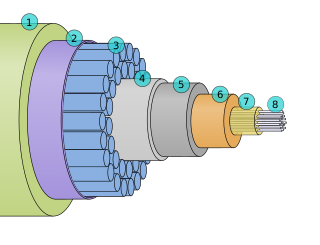

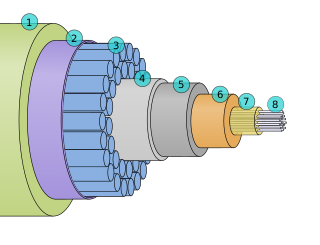

A submarine communications cable is a cable laid on the seabed between land-based stations to carry telecommunication signals across stretches of ocean and sea. The first submarine communications cables were laid beginning in the 1850s and carried telegraphy traffic, establishing the first instant telecommunications links between continents, such as the first transatlantic telegraph cable which became operational on 16 August 1858.

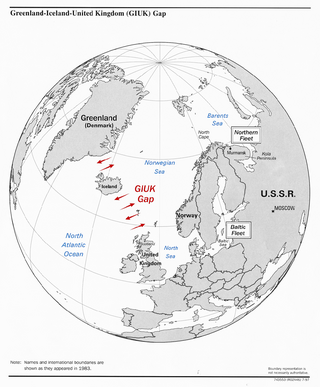

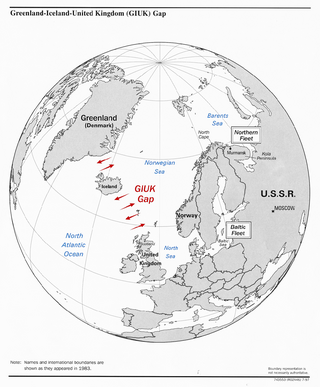

The GIUK gap is an area in the northern Atlantic Ocean that forms a naval choke point. Its name is an acronym for Greenland, Iceland, and the United Kingdom, the gap being the two stretches of open ocean among these three landmasses. It separates the Norwegian Sea and the North Sea from the open Atlantic Ocean. The term is typically used in relation to military topics. The area has for some nations been considered strategically important since the beginning of the 20th century.

Critical infrastructure, or critical national infrastructure (CNI) in the UK, describes infrastructure considered essential by governments for the functioning of a society and economy and deserving of special protection for national security. Critical infrastructure has traditionally been viewed as under the scope of government due to its strategic importance, yet there's an observable trend towards its privatization, raising discussions about how the private sector can contribute to these essential services.

A cybersecurity regulation comprises directives that safeguard information technology and computer systems with the purpose of forcing companies and organizations to protect their systems and information from cyberattacks like viruses, worms, Trojan horses, phishing, denial of service (DOS) attacks, unauthorized access and control system attacks. While cybersecurity regulations aim to minimize cyber risks and enhance protection, the uncertainty arising from frequent changes or new regulations can significantly impact organizational response strategies.

Maritime security is an umbrella term informed to classify issues in the maritime domain that are often related to national security, marine environment, economic development, and human security. This includes the world's oceans but also regional seas, territorial waters, rivers and ports, where seas act as a “stage for geopolitical power projection, interstate warfare or militarized disputes, as a source of specific threats such as piracy, or as a connector between states that enables various phenomena from colonialism to globalization”. The theoretical concept of maritime security has evolved from a narrow perspective of national naval power projection towards a buzzword that incorporates many interconnected sub-fields. The definition of the term maritime security varies and while no internationally agreed definition exists, the term has often been used to describe both existing, and new regional and international challenges to the maritime domain. The buzzword character enables international actors to discuss these new challenges without the need to define every potentially contested aspect of it. Maritime security is of increasing concern to the global shipping industry, where there are a wide range of security threats and challenges. Some of the practical issues clustered under the term of maritime security include crimes such as piracy, armed robbery at sea, trafficking of people and illicit goods, illegal fishing or marine pollution. War, warlike activity, maritime terrorism and interstate rivalry are also maritime security concerns.

Šventoji is a resort town on the coast of the Baltic Sea in Lithuania. Administratively it is part of Palanga City Municipality. The total population of Šventoji as of 2012 was 2631. The town is located about 12 km north of Palanga center and close to the border with Latvia. Further north of the town is Būtingė and its oil terminal. Šventoji River flows into the Baltic sea at the town. The town also has a famous lighthouse, which is located 780 meters from the sea. Its height is 39 meters. The town is a popular summer resort for families, during summer it has many cafes, restaurants and various attractions for the visitors.

Maritime domain awareness (MDA) is defined by the International Maritime Organization as the effective understanding of anything associated with the maritime domain that could impact the security, safety, economy, or environment. MDA is said to work as a ‘key enabler’ for other maritime security issues, such as anti-piracy patrols, in the way that in order to do effective patrols you need to have the ability of conducting effective MDA. The maritime domain is defined as all areas and things of, on, under, relating to, adjacent to, or bordering on a sea, ocean, or other navigable waterway, including all maritime-related activities, infrastructure, people, cargo, and vessels and other conveyances.

The Arctic Policy of the Kingdom of Denmark defines the Kingdom's foreign relations and policies with other Arctic countries, and the Kingdom's strategy for the Arctic on issues occurring within the geographic boundaries of "the Arctic" or related to the Arctic or its peoples. In order to clearly understand the Danish geopolitical importance of the Arctic, it is necessary to mention Denmark's territorial claims in areas beyond its exclusive EEZ in areas around the Faroe Islands and north of Greenland covering parts of the North Pole, which is also claimed by Russia.

A submarine pipeline is a pipeline that is laid on the seabed or below it inside a trench. In some cases, the pipeline is mostly on-land but in places it crosses water expanses, such as small seas, straits and rivers. Submarine pipelines are used primarily to carry oil or gas, but transportation of water is also important. A distinction is sometimes made between a flowline and a pipeline. The former is an intrafield pipeline, in the sense that it is used to connect subsea wellheads, manifolds and the platform within a particular development field. The latter, sometimes referred to as an export pipeline, is used to bring the resource to shore. Sizeable pipeline construction projects need to take into account many factors, such as the offshore ecology, geohazards and environmental loading – they are often undertaken by multidisciplinary, international teams.

Offshore installation security is the protection of maritime installations from intentional harm. As part of general maritime security, offshore installation security is defined as the installation's ability to combat unauthorized acts designed to cause intentional harm to the installation. The security of offshore installations is vital as not only may a threat result in personal, economic, and financial losses, but it also concerns the strategic aspects of the petroleum market and geopolitics.

The European Union Maritime Security Strategy is a maritime security strategy of the European Union. It was first adopted by EU member states in June 2014 and later revised in 2023 due to geopolitical changes. It provides a framework for the EU's actions within maritime security to promote more coherent approaches to identified maritime security challenges.

Seabed warfare is undersea warfare which takes place on or in relation to the seabed.

The European Union is one of the main anti-piracy actors in the Gulf of Guinea (GoG). At any one time, the EU has on average 30 owned or flagged vessels in the region. The piracy in the Gulf of Guinea is therefore a threat towards the EU, and as a response the organization adopted its strategy on the Gulf of Guinea in March 2014. The Strategy on the Gulf of Guinea is a 12-page document with the scope of the problem, what have previously been done, responses and the way forward with four strategic objectives. The EU's overriding objective are:

- to build a common understanding in regional countries of the threat and its long-term effect and the need to address the piracy issues among the regional and international community.

- to help the governments in the region to ensure maritime awareness, security and the rule of law by building robust institutions and maritime administrations.

- to assist vulnerable economies to withstand criminal or violent activity and to build resilience to communities.

- to strengthen cooperation between the countries and organizations on the region to fight threats both on land and sea.

The Multi-Role Ocean Surveillance Ship (MROSS) is a type of research and surveillance ship in development since 2021 for the United Kingdom's Royal Fleet Auxiliary. The first ship, RFA Proteus, is a commercial ship converted to the role which entered service in October 2023. The second ship is planned, potentially as a new build vessel. Both ships are to be used by the RFA to research and protect critical undersea national infrastructure, such as undersea cables and gas pipelines, in both British and international waters.

Gregory Falco is an American inventor and researcher. Falco is a professor at Cornell University. He is a pioneer in the field of cybersecurity research and its aerospace applications. Falco is the founding chair of IEEE's Standard for Space System Cybersecurity and the NATO Country Project Director for the NATO Science for Peace and Security effort to reroute the internet to space.

Hywind Tampen is a floating offshore wind farm 140 km off the Norwegian coast in the North Sea owned by the Norwegian state-owned energy company, Equinor. The turbines are mounted on cylindrical concrete spar-buoy foundations.

Environmental maritime crime constitutes one of the key components of the broader domain of blue crime, and it describes and includes activities that detrimentally impact the marine environment. Its effects have had extremely deleterious impacts on marine life, both in terms of affecting marine ecosystems and the life quality of coastal citizens, with damages that are often not reparable.

On July 17th 2024, it was announced at the State Opening of Parliament that the Labour government will introduce the Cyber Security and Resilience Bill (CS&R). The proposed legislation is intended to update the existing Network and Information Security Regulations 2018, known as UK NIS. CS&R will strengthen the UK's cyber defences and resilience to hostile attacks thus ensuring that the infrastructure and critical services relied upon by UK companies are protected by addressing vulnerabilities, while ensuring the digital economy can deliver growth.

Russian hybrid warfare are Russian efforts to foster instability in other countries using conventional and unconventional means, while avoiding all-out war.