Polynesian mythology encompasses the oral traditions of the people of Polynesia together with those of the scattered cultures known as the Polynesian outliers. Polynesians speak languages that descend from a language reconstructed as Proto-Polynesian – probably spoken in the Tonga and Samoa area around 1000 BC.

In the traditions of ancient Hawaiʻi, Kanaloa is a god symbolized by the squid or by the octopus, and is typically associated with Kāne. It is also an alternative name for the island of Kahoʻolawe.

The Auckland Islands are an archipelago of New Zealand, lying 465 kilometres (290 mi) south of the South Island. The main Auckland Island, occupying 510 km2 (200 sq mi), is surrounded by smaller Adams Island, Enderby Island, Disappointment Island, Ewing Island, Rose Island, Dundas Island, and Green Island, with a combined area of 626 km2 (240 sq mi). The islands have no permanent human inhabitants.

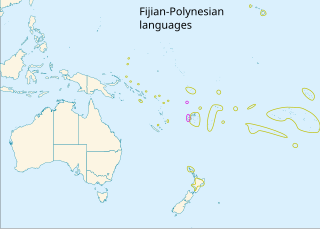

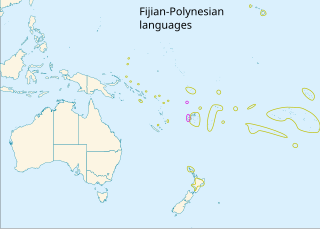

The Polynesian languages form a genealogical group of languages, itself part of the Oceanic branch of the Austronesian family.

Pacific Islanders, Pasifika, Pasefika, Pacificans or rarely Pacificers are the peoples of the Pacific Islands. As an ethnic/racial term, it is used to describe the original peoples—inhabitants and diasporas—of any of the three major subregions of Oceania.

In Polynesian mythology, Hawaiki is the original home of the Polynesians, before dispersal across Polynesia. It also features as the underworld in many Māori stories.

Polynesians are an ethnolinguistic group of closely related ethnic groups who are native to Polynesia, an expansive region of Oceania in the Pacific Ocean. They trace their early prehistoric origins to Island Southeast Asia and form part of the larger Austronesian ethnolinguistic group with an Urheimat in Taiwan. They speak the Polynesian languages, a branch of the Oceanic subfamily of the Austronesian language family. The Indigenous Māori people constitute the largest Polynesian population, followed by Samoans, Native Hawaiians, Tahitians, Tongans and Cook Islands Māori

Polynesian culture is the culture of the indigenous peoples of Polynesia who share common traits in language, customs and society. The development of Polynesian culture is typically divided into four different historical eras:

Kupe was a legendary Polynesian explorer who was the first person to discover New Zealand, according to Māori oral history. It is likely that Kupe existed historically but this is difficult to confirm. He is generally held to have been born to a father from Rarotonga and a mother from Raiatea, and probably spoke a Māori proto-language similar to Cook Islands Māori or Tahitian. His voyage to New Zealand ensured that the land was known to the Polynesians, and he would therefore be responsible for the genesis of the Māori people.

Various Māori traditions recount how their ancestors set out from their homeland in waka hourua, large twin-hulled ocean-going canoes (waka). Some of these traditions name a homeland called Hawaiki.

In Māori mythology, Te Wheke-a-Muturangi is a monstrous octopus destroyed in Whekenui Bay, Tory Channel or at Patea by Kupe the navigator.

Kurī is the Māori name for the extinct Polynesian dog. It was introduced to New Zealand by the Polynesian ancestors of the Māori during their migration from East Polynesia in the 13th century AD. According to Māori tradition, the demigod Māui transformed his brother-in-law Irawaru into the first dog.

Polynesian navigation or Polynesian wayfinding was used for thousands of years to enable long voyages across thousands of kilometers of the open Pacific Ocean. Polynesians made contact with nearly every island within the vast Polynesian Triangle, using outrigger canoes or double-hulled canoes. The double-hulled canoes were two large hulls, equal in length, and lashed side by side. The space between the paralleled canoes allowed for storage of food, hunting materials, and nets when embarking on long voyages. Polynesian navigators used wayfinding techniques such as the navigation by the stars, and observations of birds, ocean swells, and wind patterns, and relied on a large body of knowledge from oral tradition.

In Māori mythology, Muturangi, also known as Ruamuturangi, was a renowned high priest presiding over Taputapuatea marae at Rangiatea in French Polynesia.

Polynesia is a subregion of Oceania, made up of more than 1,000 islands scattered over the central and southern Pacific Ocean. The indigenous people who inhabit the islands of Polynesia are called Polynesians. They have many things in common, including language relatedness, cultural practices, and traditional beliefs. In centuries past, they had a strong shared tradition of sailing and using stars to navigate at night.

Ui-te-Rangiora or Hui Te Rangiora is a legendary Polynesian navigator from Rarotonga who is claimed to have sailed to the Southern Ocean and sometimes to have discovered Antarctica.

The Polynesian Leaders Group (PLG) is an international governmental cooperation group bringing together four independent countries and eight self-governing territories in Polynesia.

There have been changing views about initial Polynesian discovery and settlement of Hawaii, beginning with Abraham Fornander in the late 19th century and continuing through early archaeological investigations of the mid-20th century. There is no definitive date for the Polynesian discovery of Hawaii. Through the use of more advanced radiocarbon methods, taxonomic identification of samples, and stratigraphic archaeology, during the 2000s the consensus was established that the first arrived in Kauai sometime around 1000 AD, and in Oahu sometime between 1100 AD and 1200 AD. However, with more testing and refined samples, including chronologically tracing settlements in Society Islands and the Marquesas, two archipelagoes which have long been considered to be the immediate source regions for the first Polynesian voyagers to Hawaii, it has been concluded that the settlement of the Hawaiian Islands took place around 1219 to 1266 AD, with the paleo-environmental evidence of agriculture indicating the Ancient Hawaiian population to have peaked around 1450 AD around 140,000 to 200,000.

New Zealand's archaeology started in the early 1800s and was largely conducted by amateurs with little regard for meticulous study. However, starting slowly in the 1870s detailed research answered questions about human culture, that have international relevance and wide public interest.

Sweet potato cultivation in Polynesia as a crop began around 1000 AD in central Polynesia. The plant became a common food across the region, especially in Hawaii, Easter Island and New Zealand, where it became a staple food. By the 1600s in central Polynesia, traditional cultivars were being replaced with hardier and larger varieties from the Americas. Many traditional cultivars are still grown across Polynesia, but they are rare and are not widely commercially grown.