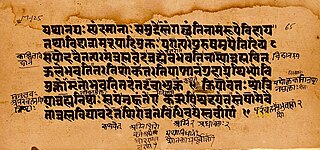

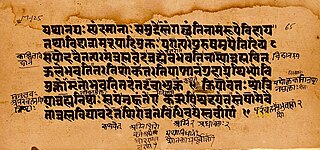

The Upanishads are late Vedic and post-Vedic Sanskrit texts that "document the transition from the archaic ritualism of the Veda into new religious ideas and institutions" and the emergence of the central religious concepts of Hinduism. They are the most recent addition to the Vedas, the oldest scriptures of Hinduism, and deal with meditation, philosophy, consciousness, and ontological knowledge. Earlier parts of the Vedas dealt with mantras, benedictions, rituals, ceremonies, and sacrifices.

Yajna in Hinduism refers to any ritual done in front of a sacred fire, often with mantras. Yajna has been a Vedic tradition, described in a layer of Vedic literature called Brahmanas, as well as Yajurveda. The tradition has evolved from offering oblations and libations into sacred fire to symbolic offerings in the presence of sacred fire (Agni).

The Chandogya Upanishad is a Sanskrit text embedded in the Chandogya Brahmana of the Sama Veda of Hinduism. It is one of the oldest Upanishads. It lists as number 9 in the Muktika canon of 108 Upanishads.

The Mundaka Upanishad is an ancient Sanskrit Vedic text, embedded inside Atharva Veda. It is a Mukhya (primary) Upanishad, and is listed as number 5 in the Muktika canon of 108 Upanishads of Hinduism. It is among the most widely translated Upanishads.

Panchala was an ancient kingdom of northern India, located in the Ganges-Yamuna Doab of the Upper Gangetic plain which is identified as Kanyakubja or region around Kannauj. During Late Vedic times, it was one of the most powerful states of ancient India, closely allied with the Kuru Kingdom. By the c. 5th century BCE, it had become an oligarchic confederacy, considered one of the solasa (sixteen) mahajanapadas of the Indian subcontinent. After being absorbed into the Mauryan Empire, Panchala regained its independence until it was annexed by the Gupta Empire in the 4th century CE.

The Mahāvākyas are "The Great Sayings" of the Upanishads, as characterized by the Advaita school of Vedanta with mahā meaning great and vākya, a sentence. Most commonly, Mahāvākyas are considered four in number,

Gautama, was a sage in Hinduism and son of Brahmin sage Dirghatamas who is also mentioned in Jainism and Buddhism. Gautama is mentioned in the Yajurveda, Ramayana, and Gaṇeśa Pūrana and is known for cursing his wife Ahalyā. Another important story related to Gautama is about the creation of river Godavari, which is also known as Gautami.

Uddalaka Aruni, also referred to as Uddalaka or Aruni or Uddalaka Varuni, is a revered Vedic sage of Hinduism. He is mentioned in many Vedic era Sanskrit texts, and his philosophical teachings are among the center piece in the Brihadaranyaka Upanishad and Chandogya Upanishad, two of the oldest Upanishadic scriptures. A famed Vedic teacher, Aruni lived a few centuries before the Buddha, and attracted students from far regions of the Indian subcontinent; some of his students such as Yajnavalkya are also highly revered in the Hindu traditions. Both Aruni and Yajnavalkya are among the most frequently mentioned Upanishadic teachers in Hinduism.

Svetaketu, also spelt Shvetaketu, was a sage and he is mentioned in the Chandogya Upanishad. He was the son of sage Uddalaka, whose real name was Aruni, and represents the quintessential seeker of knowledge. The Upanishads entail the journey of Svetaketu from ignorance to knowledge of the self and truth (sat).

Shandilya was a Vedic Rishi and was the progenitor of the Śāṇḍilya gotra. The name derives from the Sanskrit words Śaṇ, and Dilam (Moon), thus meaning Full Moon, therefore implying Śhāṇḍilya had great devotion towards the Moon God. His descendants have a matrilineal descent from the Chandravamsha.

Raikva, the poor unknown cart-driver, appears in Chapter IV of the Chandogya Upanishad of Muktika canon where it is learnt that he knew That which was knowable and needed to be known, he knew That from which all this had originated. Along with Uddalaka, Prachinshala, Budila, Sarkarakshaya and Indradyumna, who respectively held earth, heaven, water, space and air to be the substrata of all things, and many others, Raikva was one of the leading Cosmological and Psychological philosophers of the Upanishads. He imparted the Samvarga Vidya to King Janasruti. Like Indradyumna he too held air to be substratum of all things.

Non-difference is the nearest English translation of the Sanskrit word abheda, meaning non-existence of difference. In Vedanta philosophy this word plays a vital role in explaining the indicatory mark in respect of the unity of the individual self with the Infinite or Brahman.

Avyakta, meaning "not manifest", "devoid of form" etc., is the word ordinarily used to denote Prakrti on account of subtleness of its nature and is also used to denote Brahman, which is the subtlest of all and who by virtue of that subtlety is the ultimate support (asraya) of Prakrti. Avyakta as a category along with Mahat and Purusa plays an important role in the later Samkhya philosophy even though the Bhagavad Gita III.42 retaining the psychological categories altogether drops out the Mahat and the Avyakta (Unmanifest), the two objective categories.

Anavrtti is a Vedic term which means – non-return to a body, final emancipation. This word refers to the Jivanmukta.

Panchagni vidyā means - meditation on the five fires. This vidyā or knowledge appears in the Chandogya Upanishad and the Brihadaranyaka Upanishad. It is one of the forty-one prescribed Vedic rituals.

The Paramahamsa Parivrajaka Upanishad, is a medieval era Sanskrit text and a minor Upanishad of Hinduism. It is one of the 31 Upanishads attached to the Atharvaveda, and classified as one of the 19 Sannyasa Upanishads.

The Devi Upanishad, is one of the minor Upanishads of Hinduism and a text composed in Sanskrit. It is one of the 19 Upanishads attached to the Atharvaveda, and is classified as one of the eight Shakta Upanishads. It is, as an Upanishad, a part of the corpus of Vedanta literature collection that present the philosophical concepts of Hinduism.

The Pranagnihotra Upanishad is a minor Upanishad of Hinduism. In the anthology of 108 Upanishads of the Muktika canon, narrated by Rama to Hanuman, it is listed at number 94. The Sanskrit text is one of the 22 Samanya Upanishads, part of the Vedanta school of Hindu philosophy literature and is attached to the Atharva Veda. The Upanishad comprises 23 verses.

The Jabala Upanishad, also called Jabalopanisad, is a minor Upanishad of Hinduism. The Sanskrit text is one of the 20 Sannyasa Upanishads, and is attached to the Shukla Yajurveda.

Keśin Dālbhya was a king of Panchala during the Late Vedic period, most likely between c. 900 and 750 BCE.