The Indo-European languages are a language family native to the overwhelming majority of Europe, the Iranian plateau, and the northern Indian subcontinent. Some European languages of this family—English, French, Portuguese, Russian, Dutch, and Spanish—have expanded through colonialism in the modern period and are now spoken across several continents. The Indo-European family is divided into several branches or sub-families, of which there are eight groups with languages still alive today: Albanian, Armenian, Balto-Slavic, Celtic, Germanic, Hellenic, Indo-Iranian, and Italic; another nine subdivisions are now extinct.

The Anatolian languages are an extinct branch of Indo-European languages that were spoken in Anatolia, part of present-day Turkey. The best known Anatolian language is Hittite, which is considered the earliest-attested Indo-European language.

The laryngeal theory is a theory in historical linguistics positing that the Proto-Indo-European language included a number of laryngeal consonants that are not reconstructable by direct application of the comparative method to the Indo-European family. The "missing" sounds remain consonants of an indeterminate place of articulation towards the back of the mouth, though further information is difficult to derive. Proponents aim to use the theory to:

Luwian, sometimes known as Luvian or Luish, is an ancient language, or group of languages, within the Anatolian branch of the Indo-European language family. The ethnonym Luwian comes from Luwiya – the name of the region in which the Luwians lived. Luwiya is attested, for example, in the Hittite laws.

Hittite, also known as Nesite, is an extinct Indo-European language that was spoken by the Hittites, a people of Bronze Age Anatolia who created an empire centred on Hattusa, as well as parts of the northern Levant and Upper Mesopotamia. The language, now long extinct, is attested in cuneiform, in records dating from the 17th to the 13th centuries BC, with isolated Hittite loanwords and numerous personal names appearing in an Old Assyrian context from as early as the 20th century BC, making it the earliest attested use of the Indo-European languages.

Proto-Indo-European (PIE) is the reconstructed common ancestor of the Indo-European language family. No direct record of Proto-Indo-European exists; its proposed features have been derived by linguistic reconstruction from documented Indo-European languages.

Palaic is an extinct Indo-European language, attested in cuneiform tablets in Bronze Age Hattusa, the capital of the Hittites. Palaic, which was apparently spoken mainly in northern Anatolia, is generally considered to be one of four primary sub-divisions of the Anatolian languages, alongside Hittite, Luwic and Lydian.

In Indo-European linguistics, the term Indo-Hittite is Edgar Howard Sturtevant's 1926 hypothesis that the Anatolian languages split off a Pre-Proto-Indo-European language considerably earlier than the separation of the remaining Indo-European languages. The prefix Indo- does not refer to the Indo-Aryan branch in particular, but stands for Indo-European, and the -Hittite part refers to the Anatolian language family as a whole.

Proto-Celtic, or Common Celtic, is the hypothetical ancestral proto-language of all known Celtic languages, and a descendant of Proto-Indo-European. It is not attested in writing but has been partly reconstructed through the comparative method. Proto-Celtic is generally thought to have been spoken between 1300 and 800 BC, after which it began to split into different languages. Proto-Celtic is often associated with the Urnfield culture and particularly with the Hallstatt culture. Celtic languages share common features with Italic languages that are not found in other branches of Indo-European, suggesting the possibility of an earlier Italo-Celtic linguistic unity.

As the Proto-Indo-European language (PIE) broke up, its sound system diverged as well, as evidenced in various sound laws associated with the daughter Indo-European languages. Especially notable is the palatalization that produced the satem languages, along with the associated ruki sound law. Other notable changes include:

Proto-Indo-Iranian, also called Proto-Indo-Iranic or Proto-Aryan, is the reconstructed proto-language of the Indo-Iranian branch of Indo-European. Its speakers, the hypothetical Proto-Indo-Iranians, are assumed to have lived in the late 3rd millennium BC, and are often connected with the Sintashta culture of the Eurasian Steppe and the early Andronovo archaeological horizon.

Brugmann's law, named for Karl Brugmann, is a sound law stating that in the Indo-Iranian languages, the earlier Proto-Indo-European *o normally became *a in Proto-Indo-Iranian but *ā in open syllables if it was followed by one consonant and another vowel. For example, the Proto-Indo-European noun for 'wood' was *dόru, which in Vedic became dāru. Everywhere else, the outcome was *a, the same as the reflexes of PIE *e and *a.

The phonology of the Proto-Indo-European language (PIE) has been reconstructed by linguists, based on the similarities and differences among current and extinct Indo-European languages. Because PIE was not written, linguists must rely on the evidence of its earliest attested descendants, such as Hittite, Sanskrit, Ancient Greek, and Latin, to reconstruct its phonology.

The roots of the reconstructed Proto-Indo-European language (PIE) are basic parts of words to carry a lexical meaning, so-called morphemes. PIE roots usually have verbal meaning like "to eat" or "to run". Roots never occurred alone in the language. Complete inflected verbs, nouns, and adjectives were formed by adding further morphemes to a root and potentially changing the root's vowel in a process called ablaut.

Proto-Indo-European accent refers to the accentual (stress) system of the Proto-Indo-European language.

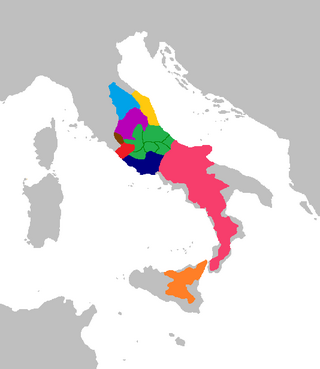

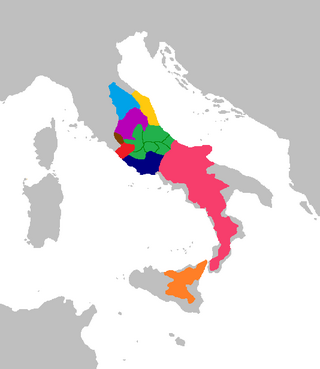

Languages of the Indo-European family are classified as either centum languages or satem languages according to how the dorsal consonants of the reconstructed Proto-Indo-European language (PIE) developed. An example of the different developments is provided by the words for "hundred" found in the early attested Indo-European languages. In centum languages, they typically began with a sound, but in satem languages, they often began with.

The Proto-Italic language is the ancestor of the Italic languages, most notably Latin and its descendants, the Romance languages. It is not directly attested in writing, but has been reconstructed to some degree through the comparative method. Proto-Italic descended from the earlier Proto-Indo-European language.

The grammar of the Hittite language has a highly conservative verbal system and rich nominal declension. The language is attested in cuneiform, and is the earliest attested Indo-European language.

This glossary gives a general overview of the various sound laws that have been formulated by linguists for the various Indo-European languages. A concise description is given for each rule; more details are given in their respective articles.

Hittite phonology is the description of the reconstructed phonology or pronunciation of the Hittite language. Because Hittite as a spoken language is extinct, thus leaving no living daughter languages, and no contemporary descriptions of the pronunciation are known, little can be said with certainty about the phonetics and the phonology of the language. Some conclusions can be made, however, by noting its relationship to the other Indo-European languages, by studying its orthography and by comparing loanwords from nearby languages.