Śūnyatā, translated most often as emptiness, vacuity, and sometimes voidness, is an Indian philosophical concept. Within Hinduism, Jainism, Buddhism and other philosophical strands, the concept has multiple meanings depending on its doctrinal context. It is either an ontological feature of reality, a meditative state, or a phenomenological analysis of experience.

In Buddhism, the term anattā or anātman refers to the doctrine of "non-self" – that no unchanging, permanent self or essence can be found in any phenomenon. While often interpreted as a doctrine denying the existence of a self, anatman is more accurately described as a strategy to attain non-attachment by recognizing everything as impermanent, while staying silent on the ultimate existence of an unchanging essence. In contrast, Hinduism asserts the existence of Atman as pure awareness or witness-consciousness, "reify[ing] consciousness as an eternal self."

The Tathāgatagarbha sūtras are a group of Mahayana sutras that present the concept of the "womb" or "embryo" (garbha) of the tathāgata, the buddha. Every sentient being has the possibility to attain Buddhahood because of the tathāgatagarbha.

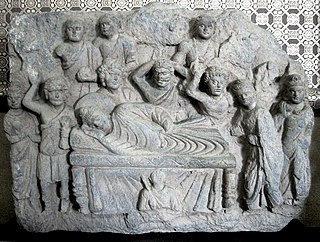

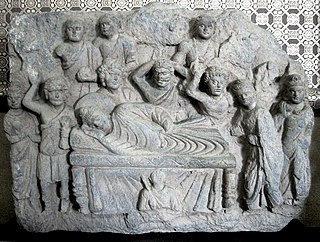

In Buddhism, parinirvana is commonly used to refer to nirvana-after-death, which occurs upon the death of someone who has attained nirvana during their lifetime. It implies a release from Saṃsāra, karma and rebirth as well as the dissolution of the skandhas.

Buddha-nature refers to several related Mahayana Buddhist terms, including tathata ("suchness") but most notably tathāgatagarbha and buddhadhātu. Tathāgatagarbha means "the womb" or "embryo" (garbha) of the "thus-gone" (tathāgata), or "containing a tathāgata", while buddhadhātu literally means "Buddha-realm" or "Buddha-substrate".

The Śrīmālādevī Siṃhanāda Sūtra is one of the main early Mahāyāna Buddhist texts belonging to the Tathāgatagarbha sūtras that teaches the doctrines of Buddha-nature and "One Vehicle" through the words of the Indian queen Śrīmālā. After its composition, this text became the primary scriptural advocate in India for the universal potentiality of Buddhahood.

Ātman, attā or attan in Buddhism is the concept of self, and is found in Buddhist literature's discussion of the concept of non-self (Anatta).

The Mahāyāna Mahāparinirvāṇa Sūtra or Nirvana Sutra is Mahāyāna Buddhist sutra of the Buddha-nature genre. Its precise date of origin is uncertain, but its early form may have developed in or by the second century CE. The original Sanskrit text is not extant except for a small number of fragments, but it survives in Chinese and Tibetan translation.

The Anūnatvāpurnatvanirdeśa is a short Mahayana text belonging to the tathagatagarbha class of sutras.

The Ratnagotravibhāga and its vyākhyā commentary, is an influential Mahāyāna Buddhist treatise on buddha-nature. The text is also known as the Mahāyānottaratantraśāstra. The RGVV was originally composed in Sanskrit, likely between the middle of the third century and no later than 433 CE. The text and its commentary are also preserved in Tibetan and Chinese translations.

In East Asian Buddhism, Shakyamuni Buddha of the Essential Teachings of the Lotus Sutra is considered the eternal Buddha. In the sixteenth chapter of the Lotus Sutra, Shakyamuni Buddha reveals that he actually attained Buddhahood in the inconceivably remote past. The Eternal Buddha is contrasted to Shakyamuni Buddha who attained enlightenment for the first time in India, which was taught in the pre-Lotus Sutra teachings.

The Tathāgatagarbha Sūtra is an influential and doctrinally striking Mahāyāna Buddhist scripture which treats of the existence of the "Tathāgatagarbha" within all sentient creatures. According to the Buddha, all sentient beings are born with buddha-nature and have the potential to become a Buddha. Physical and mental defilements of everyday life act as clouds over the this nature and usually prevent this realization. This nature is no less than the indwelling Buddha himself.

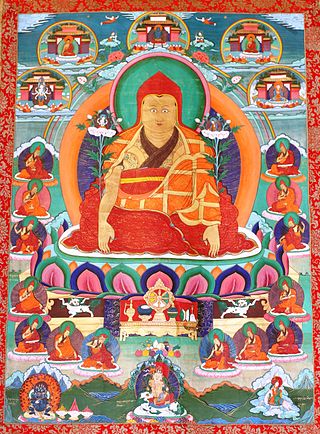

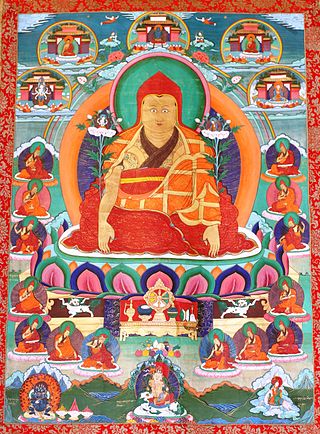

Dölpopa Shérap Gyeltsen (1292–1361), known simply as Dölpopa, was a Tibetan Buddhist master. Known as "The Buddha from Dölpo," a region in modern Nepal, he was the principal exponent of the shentong teachings, and an influential member of the Jonang tradition of Tibetan Buddhism.

Reality in Buddhism is called dharma (Sanskrit) or dhamma (Pali). This word, which is foundational to the conceptual frameworks of the Indian religions, refers in Buddhism to the system of natural laws which constitute the natural order of things. Dharma is therefore reality as-it-is (yatha-bhuta). The teaching of Gautama Buddha constitutes a method by which people can come out of their condition of suffering through developing an awareness of reality. Buddhism thus seeks to address any disparity between a person's view of reality and the actual state of things. This is called developing Right or Correct View. Seeing reality as-it-is is thus an essential prerequisite to mental health and well-being according to Buddha's teaching.

The Aṅgulimālīya Sūtra is a Mahāyāna Buddhist scripture belonging to the Tathāgatagarbha class of sūtra, which teach that the Buddha is eternal, that the non-Self and emptiness teachings only apply to the worldly sphere and not to Nirvāṇa, and that the Tathāgatagarbha is real and immanent within all beings and all phenomena. The sutra consists mostly of stanzas in verse.

In Mahayana Buddhism the icchantika is a deluded being who can never attain enlightenment (Buddhahood).

Dharmadhatu (Sanskrit) is the 'dimension', 'realm' or 'sphere' (dhātu) of the Dharma or Absolute Reality.

Nirvana is "blowing out" or "quenching" of the activities of the worldly mind and its related suffering. Nirvana is the goal of the Hinayana and Theravada Buddhist paths, and marks the soteriological release from worldly suffering and rebirths in saṃsāra. Nirvana is part of the Third Truth on "cessation of dukkha" in the Four Noble Truths, and the "summum bonum of Buddhism and goal of the Eightfold Path."

Luminous mind is a Buddhist term which appears only rarely in the Pali Canon, but is common in the Mahayana sūtras and central to the Buddhist tantras. It is variously translated as "brightly shining mind", or "mind of clear light" while the related term luminosity is also translated as "clear light" or "luminosity" in Tibetan Buddhist contexts or, "purity" in East Asian contexts.

Mahāyāna is a term for a broad group of Buddhist traditions, texts, philosophies, and practices. Mahāyāna Buddhism developed in India and is considered one of the three main existing branches of Buddhism. Mahāyāna accepts the main scriptures and teachings of early Buddhism but also recognizes various doctrines and texts that are not accepted by Theravada Buddhism as original. These include the Mahāyāna Sūtras and their emphasis on the bodhisattva path and Prajñāpāramitā. Vajrayāna or Mantra traditions are a subset of Mahāyāna, which make use of numerous tantric methods considered to be faster and more powerful at achieving Buddhahood by Vajrayānists.