A carabiner or karabiner, often shortened to biner or to crab, colloquially known as a (climbing) clip, is a specialized type of shackle, a metal loop with a spring-loaded gate used to quickly and reversibly connect components, most notably in safety-critical systems. The word comes from the German Karabiner, short for Karabinerhaken, meaning "carbine hook," as the device was used by carabiniers to attach their carbines to their belts.

A climbing harness is a piece of equipment that allows a climber to tie in to the safety of a rope. It is used in rock and ice climbing, abseiling, and lowering; this is in contrast to other activities requiring ropes for access or safety such as industrial rope work, construction, and rescue and recovery, which use safety harnesses instead.

Webbing is a strong fabric woven as a flat strip or tube of varying width and fibres, often used in place of rope. It is a versatile component used in climbing, slacklining, furniture manufacturing, automobile safety, auto racing, towing, parachuting, military apparel, load securing, and many other fields.

Glossary of climbing terms relates to rock climbing, mountaineering, and to ice climbing.

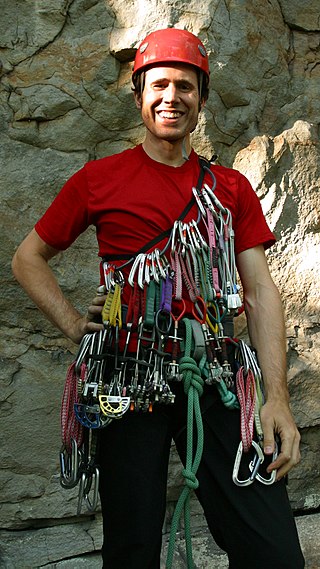

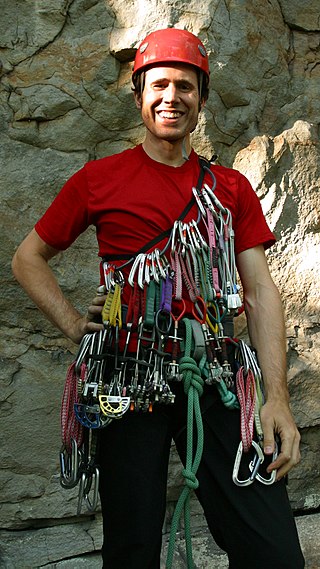

Rock-climbing equipment varies with the specific type of climbing that is undertaken. Bouldering needs the least equipment outside of climbing shoes, climbing chalk and optional crash pads. Sport climbing adds ropes, harnesses, belay devices, and quickdraws to clip into pre-drilled bolts. Traditional climbing adds the need to carry a "rack" of temporary passive and active protection devices. Multi-pitch climbing, and the related big wall climbing, adds devices to assist in ascending and descending fixed ropes. Finally, aid climbing uses unique equipment to give mechanical assistance to the climber in their upward movement.

Lead climbing is a technique in rock climbing where the 'lead climber' clips their rope to the climbing protection as they ascend a pitch of the climbing route, while their 'second' remains at the base of the route belaying the rope to protect the 'lead climber' in the event that they fall. The term is used to distinguish between the two roles, and the greater effort and increased risk, of the role of the 'lead climber'.

In rock climbing, a bolt is a permanent anchor fixed into a hole drilled in the rock as a form of climbing protection. Most bolts are either self-anchoring expansion bolts or fixed in place with liquid resin. Climbing routes that are bolted are known as sport climbs, and those that do not use bolts, are known as traditional climbs.

In lead climbing using a dynamic rope, the fall factor (f) is the ratio of the height (h) a climber falls before the climber's rope begins to stretch and the rope length (L) available to absorb the energy of the fall,

The Munter hitch, also known as the Italian hitch, mezzo barcaiolo or the crossing hitch, is a simple adjustable knot, commonly used by climbers, cavers, and rescuers to control friction in a life-lining or belay system. To climbers, this hitch is also known as HMS, the abbreviation for the German term Halbmastwurfsicherung, meaning half clove hitch belay. This technique can be used with a special "pear-shaped" HMS locking carabiner, or any locking carabiner wide enough to take two turns of the rope.

The Bachmann hitch is a friction hitch, named after the Austrian alpinist Franz Bachmann. It is useful when the friction hitch needs to be reset quickly or often or made to be self-tending as in crevasse and self-rescue.

An ascender is a device used for directly ascending, or for facilitating protection, with a fixed rope when climbing on steep mountain terrain. A form introduced in the 1950s became so popular it began the term "Jumar" for the device, and the verb "to jumar" to describe its use in ascending.

A sling is an item of climbing equipment consisting of a tied or sewn loop of webbing. These can be wrapped around sections of rock, hitched to other pieces of equipment, or tied directly to a tensioned line using a Prusik style knot. They may be used as anchors, to extend an anchor to reduce rope drag, in anchor equalization, or to climb a rope.

In rock climbing, an anchor can be any device or method for attaching a climber, rope, or load to a climbing surface—typically rock, ice, steep dirt, or a building—either permanently or temporarily. The intention of an anchor is case-specific but is usually for fall protection, primarily fall arrest and fall restraint. Climbing anchors are also used for hoisting, holding static loads, or redirecting a rope.

In climbing, a Tyrolean traverse is a technique that enables climbers to cross a void between two fixed points, such as between a headland a detached rock pillar, or between two points that enable the climbers to cross over an obstacle such as chasm or ravine, or over a fast moving river. Originally developed by Tyrolean mountaineers in the Dolomites in the late 19th to early 20th century, Tyrolean traverses are used in other areas including in caving and in mountain rescue situations.

A dynamic rope is a specially constructed, somewhat elastic rope used primarily in rock climbing, ice climbing, and mountaineering. This elasticity, or stretch, is the property that makes the rope dynamic—in contrast to a static rope that has only slight elongation under load. Greater elasticity allows a dynamic rope to more slowly absorb the energy of a sudden load, such from arresting a climber's fall, by reducing the peak force on the rope and thus the probability of the rope's catastrophic failure. A kernmantle rope is the most common type of dynamic rope now used. Since 1945, nylon has, because of its superior durability and strength, replaced all natural materials in climbing rope.

The American Death Triangle, also known as the "American Triangle", "Triangle Anchor" or simply the "Death Triangle", is a dangerous type of rock and ice climbing anchor infamous for both magnifying load forces on fixed anchors and lack of redundancy in attachment to the anchor.

The Garda Hitch, also known as the Alpine Clutch, is a type of climbing knot that can only be moved in one direction. It is often used in climbing and mountaineering, such as in pulley systems to haul loads up a cliff. However, the Garda Hitch has some drawbacks, including being difficult to release under load, difficult to inspect, and adding significant friction to a pulley system. It can be challenging to determine which direction the rope will move freely and which direction it will lock just by looking at it. To tie a Garda Hitch, you need two similar carabiners, and it works best with two identical oval carabiners. While "D" carabiners can also be used, there is a risk of them unclipping.

A hex is an item of rock-climbing equipment used to protect climbers from falls. They are intended to be wedged into a crack or other opening in the rock, and do not require a hammer to place. They were developed as an alternative to pitons, which are hammered into cracks, damaging the rock. Most commonly, a carabiner will be used to join the hex to the climbing rope by means of a loop of webbing, cord or a cable which is part of the hex.

Saxon Switzerland is the largest and one of the best-known rock climbing regions in Germany, located in the Free State of Saxony. The region is largely coterminous with the natural region of the same name, Saxon Switzerland, but extends well beyond the territory of the National Park within it. It includes the western part of the Elbe Sandstone Mountains and is the oldest non-Alpine rock climbing region in Germany. Its history of climbing dates back to the first ascent in modern times of the Falkenstein by Bad Schandau gymnasts in 1864. Currently, there are over 1,100 peaks with more than 17,000 climbing routes in the Saxon Switzerland area.