Mountaineering, mountain climbing, or alpinism is a set of outdoor activities that involves ascending mountains. Mountaineering-related activities include traditional outdoor climbing, skiing, and traversing via ferratas that have become sports in their own right. Indoor climbing, sport climbing, and bouldering are also considered variants of mountaineering by some, but are part of a wide group of mountain sports.

Glossary of climbing terms relates to rock climbing, mountaineering, and to ice climbing.

A crevasse is a deep crack that forms in a glacier or ice sheet. Crevasses form as a result of the movement and resulting stress associated with the shear stress generated when two semi-rigid pieces above a plastic substrate have different rates of movement. The resulting intensity of the shear stress causes a breakage along the faces.

Mountaineering: The Freedom of the Hills is often considered the standard textbook for mountaineering and climbing in North America. The book was first published in 1960 by The Mountaineers of Seattle, Washington. The book was written by a team of over 40 experts in the field.

A glissade is a climbing technique mostly used in mountaineering and alpine climbing where a climber starts a controlled slide down a snow and/or ice slope to speed up their descent. Glissading is ideally done later in the day when the snow is softer.

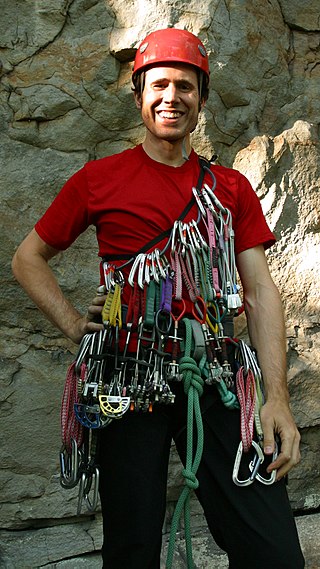

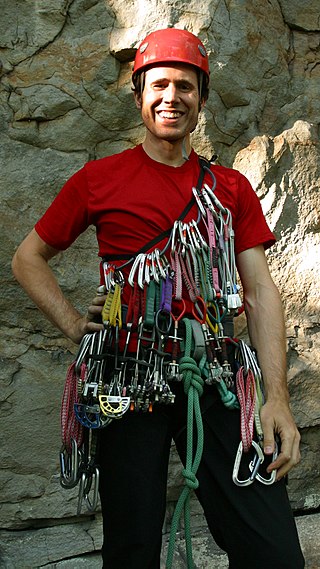

Rock-climbing equipment varies with the specific type of climbing that is undertaken. Bouldering needs the least equipment outside of climbing shoes, climbing chalk and optional crash pads. Sport climbing adds ropes, harnesses, belay devices, and quickdraws to clip into pre-drilled bolts. Traditional climbing adds the need to carry a "rack" of temporary passive and active protection devices. Multi-pitch climbing, and the related big wall climbing, adds devices to assist in ascending and descending fixed ropes. Finally, aid climbing uses unique equipment to give mechanical assistance to the climber in their upward movement.

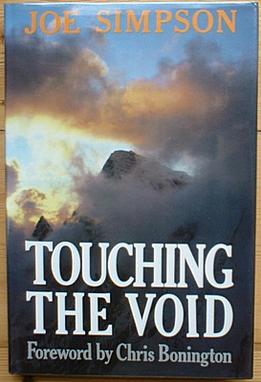

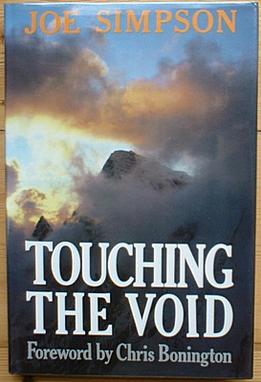

Touching the Void is a 1988 book by Joe Simpson, recounting his and Simon Yates's near fatal descent after climbing the 6,344-metre (20,814 ft) peak Siula Grande in the Peruvian Andes. Approximately 15% of the book is written by Yates. It has sold over a million copies and has been translated into over 20 languages.

In climbing, a pitch is a section of a climbing route between two belay points, and is most commonly related to the task of lead climbing, but is also related to abseiling. Climbing on routes that require only one pitch is known as single-pitch climbing, and climbing on routes with more than one pitch is known as multi-pitch climbing.

Multi-pitch climbing is a type of climbing that typically takes place on routes that are more than a single rope length in height, and thus where the lead climber cannot complete the climb as a single pitch. Where the number of pitches exceeds 6–10, it can become big wall climbing, or where the pitches are in a mixed rock and ice mountain environment, it can become alpine climbing. Multi-pitch rock climbs can come in traditional, sport, and aid formats. Some have free soloed multi-pitch routes.

An ascender is a device used for directly ascending, or for facilitating protection, with a fixed rope when climbing on steep mountain terrain. A form introduced in the 1950s became so popular it began the term "Jumar" for the device, and the verb "to jumar" to describe its use in ascending.

In climbing and mountaineering, a fixed-rope is the practice of installing networks of in-situ anchored static climbing ropes on climbing routes to assist any following climbers to ascend more rapidly—and with less effort—by using mechanical aid devices called ascenders. Fixed ropes also allow climbers to descend rapidly using mechanical devices called descenders. Fixed ropes also help to identify the line of the climbing route in periods of low visibility. The act of ascending a fixed rope is also called jumaring, which is the name of a type of ascender device, or also called jugging in the US.

The self-arrest is a climbing technique mostly used in mountaineering and alpine climbing where a climber who has fallen and is sliding uncontrollably down a snow or ice-covered slope 'arrests' their fall by themselves by using their ice axe and their crampons.

A Prusik is a friction hitch or knot used to attach a loop of cord around a rope, applied in climbing, canyoneering, mountaineering, caving, rope rescue, ziplining, and by arborists. The term Prusik is a name for both the loops of cord used to tie the hitch and the hitch itself, and the verb is "to prusik" or "prusiking". More casually, the term is used for any friction hitch or device that can grab a rope. Due to the pronunciation, the word is often misspelled Prussik, Prussick, or Prussic.

In climbing, a Tyrolean traverse is a technique that enables climbers to cross a void between two fixed points, such as between a headland a detached rock pillar, or between two points that enable the climbers to cross over an obstacle such as chasm or ravine, or over a fast moving river. Originally developed by Tyrolean mountaineers in the Dolomites in the late 19th to early 20th century, Tyrolean traverses are used in other areas including in caving and in mountain rescue situations.

Big wall climbing is a form of rock climbing that takes place on long multi-pitch routes that normally require a full day, if not several days, to ascend. In addition, big wall routes are typically sustained and exposed, where the climbers remain suspended from the rock face, even sleeping hanging from the face, with limited options to sit down or escape unless they abseil back down the whole route, which is a complex and risky action. It is therefore a physically and mentally demanding form of climbing.

Self-rescue is a group of techniques in climbing and mountaineering where the climber(s) – sometimes having just been severely injured – use their equipment to retreat from dangerous or difficult situations on a given climbing route without calling on third party search and rescue (SAR) or mountain rescue services for help.

In climbing and mountaineering, a traverse is a section of a climbing route where the climber moves laterally, as opposed to in an upward direction. The term has broad application, and its use can range from describing a brief section of lateral movement on a pitch of a climbing route, to large multi-pitch climbing routes that almost entirely consist of lateral movement such as girdle traverses that span the entire rock face of a crag, to mountain traverses that span entire ridges connecting chains of mountain peaks.

Scaife Glacier is located on Axel Heiberg Island in the Qikiqtaaluk Region of Nunavut in the Canadian High Arctic.

A rope team is a climbing technique where two or more climbers who are attached to a single climbing rope move simultaneously together along easy-angled terrain that does not require points of fixed climbing protection to be inserted along the route. Rope teams contrast with simul-climbing, which involves only two climbers and where they are ascending steep terrain that will require many points of protection to be inserted along the route. A specific variant of a rope team is the technique of short-roping, which is used by mountain guides to help weaker clients, and which also does not employ fixed climbing protection points.

Alpine climbing is a type of mountaineering that uses any of a broad range of advanced climbing skills, including rock climbing, ice climbing, and/or mixed climbing, to summit typically large routes in an alpine environment. While alpine climbing began in the European Alps, it is used to refer to climbing in any remote mountainous area, including in the Himalayas and Patagonia. The derived term alpine style refers to the fashion of alpine climbing to be in small lightly equipped teams who carry their equipment, and do all of the climbing.