The Lizard is a peninsula in southern Cornwall, England, United Kingdom. The southernmost point of the British mainland is near Lizard Point at SW 701115; Lizard village, also known as the Lizard, is the most southerly on the British mainland, and is in the civil parish of Landewednack, the most southerly parish. The valleys of the river Helford and Loe Pool form the northern boundary, with the rest of the peninsula surrounded by sea. The area measures about 14 by 14 miles. The Lizard is one of England's natural regions and has been designated as a National Character Area 157 by Natural England. The peninsula is known for its geology and for its rare plants and lies within the Cornwall Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB).

Helston is a town and civil parish in Cornwall, England, United Kingdom. It is situated at the northern end of the Lizard Peninsula approximately 12 miles (19 km) east of Penzance and 9 miles (14 km) south-west of Falmouth. Helston is the most southerly town on the island of Great Britain and is around 1+1⁄2 miles farther south than Penzance. The population in 2011 was 11,700.

Porthleven is a town, civil parish and fishing port near Helston, Cornwall, England, United Kingdom. The most southerly port in Great Britain, it was a harbour of refuge when this part of the Cornish coastline was infamous for wrecks in the days of sail. The South West Coast Path from Somerset to Dorset passes through the town. The population at the 2011 census was 3,059.

Mount's Bay is a bay on the English Channel coast of Cornwall, England, stretching from the Lizard Point to Gwennap Head. In the north of the bay, near Marazion, is St Michael's Mount; the origin of name of the bay. In summer, it is a generally benign natural harbour. However, in winter, onshore gales present maritime risks, particularly for sailing ships. There are more than 150 known wrecks from the nineteenth century in the area. The eastern side of the bay centred around Marazion and St Michael's Mount was designated as a Marine Conservation Zone in January 2016.

Gweek is a civil parish and village in Cornwall, England, United Kingdom. It is situated approximately three miles (5 km) east of Helston. The civil parish was created from part of the parish of Constantine by boundary revision in 1986. The name Gweek is first recorded as Gwyk in 1358 and is derived from the Cornish word gwig, meaning "forest village", cognate with the Welsh gwig and Old Breton guic. Gweek village has a pub, the Black Swan, and a combined shop and post office. The village is also home to the Cornish Seal Sanctuary.

Swanpool is a small coastal saline lagoon with a shingle bar, separating it from the beach of the same name. The South West Coast Path crosses the bar. The pool is near the town of Falmouth, on the south coast of Cornwall, England, UK, between Maenporth and Gyllyngvase. A notable building in the area is Swanpool House, a 19th-century building which was occupied by American forces during the Second World War but is now in use as holiday apartments. There was formerly a mine extending beneath the lagoon.

Gunwalloe is a coastal civil parish in Cornwall, England, United Kingdom. It is situated on the Lizard Peninsula three miles (4.8 km) south of Helston and partly contains The Loe, the largest natural freshwater lake in Cornwall. The parish population including Berepper at the 2011 census was 219. The hamlets in the parish are Chyanvounder, Berepper and Chyvarloe. To the east are the Halzephron cliffs and further east the parish church.

Breage is a village and civil parish in Cornwall, England, United Kingdom. The village is 3 miles (5 km) west of Helston.

Wendron is a village and civil parish in Cornwall, England, United Kingdom. It is approximately 3 miles (5 km) to the north of Helston and 6 miles (10 km) to the west of Penryn. The parish population at the 2011 census was 2,743. The electoral ward of Wendron had a 2011 population of 4,936.

Slapton Ley is a lake on the south coast of Devon, England, separated from Start Bay by a shingle beach, known as Slapton Sands.

The River Cober is a short river in west Cornwall, England, United Kingdom. The river runs to the west of Helston into The Loe, Cornwall's largest natural lake.

Degibna is a hamlet and farm in the parish of Helston, Cornwall, England, UK. It lies on the eastern bank of the largest natural freshwater lake in Cornwall, The Loe, and forms part of the Penrose Estate.

Penrose is a house and National Trust estate amounting to 1536 acres, east of Porthleven and in the civil parish of Sithney, Cornwall, England. The estate includes Loe Pool and Loe Bar which was given into the ownership of the National Trust in 1974 by Lt. Cdr. J. P. Rogers, and stretches along the coast to Gunwalloe. The estate was owned by the Penrose family for several hundred years before 1771 when it was bought for £11,000 by the Rogers family, whose descendants still reside in Penrose House.

Rinsey is a hamlet in the civil parish of Breage, in Cornwall, England, United Kingdom. It is located off the main A394 road between Helston and Penzance. The nearby hamlet of Rinsey Croft is located 1 km to the north-east. The nearby cliffs and beach are owned and managed by the National Trust and part of Rinsey East Cliff is designated as the Porthcew Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) for its geological interest. The South West Coast Path passes through the property. Rinsey lies within the Cornwall Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB).

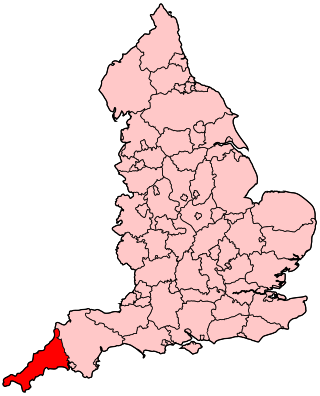

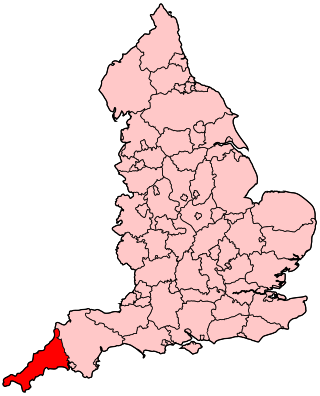

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to Cornwall: Cornwall – ceremonial county and unitary authority area of England within the United Kingdom. Cornwall is a peninsula bordered to the north and west by the Celtic Sea, to the south by the English Channel, and to the east by the county of Devon, over the River Tamar. Cornwall is also a royal duchy of the United Kingdom. It has an estimated population of half a million and it has its own distinctive history and culture.

John Jope Rogers was the owner of Penrose, a house and estate near the Cornish town of Helston. The estate included Loe Pool, the largest lake in Cornwall, now owned by the National Trust. He was also an author and Conservative MP for Helston, Cornwall from 1859 to 1865.

Presented below is an alphabetical index of articles related to Cornwall: