Minangkabau is an Austronesian language spoken by the Minangkabau of West Sumatra, the western part of Riau, South Aceh Regency, the northern part of Bengkulu and Jambi, also in several cities throughout Indonesia by migrated Minangkabau. The language is also a lingua franca along the western coastal region of the province of North Sumatra, and is even used in parts of Aceh, where the language is called Aneuk Jamee.

The name varnish tree may refer to numerous species of tree:

Aleurites is a small genus of arborescent flowering plants in the Euphorbiaceae, first described as a genus in 1776. It is native to China, the Indian Subcontinent, Southeast Asia, Papuasia, and Queensland. It is also reportedly naturalized on various islands as well as scattered locations in Africa, South America, and Florida.

The Agency for Language Development and Cultivation, formerly the Language and Book Development Agency and the Language Centre, is the institution responsible for standardising and regulating the Indonesian language as well as maintaining the indigenous languages of Indonesia. It is an agency under the Ministry of Education, Culture, Research and Technology of Indonesia.

Candlenut oil or kukui nut oil is extracted from the nut of Aleurites moluccanus, the candlenut or kuku'i.

Tidore is a language of North Maluku, Indonesia, spoken by the Tidore people. The language is centered on the island of Tidore, but it is also spoken in some areas of the neighbouring Halmahera. Historically, it was the primary language of the Sultanate of Tidore, a major Moluccan Muslim state.

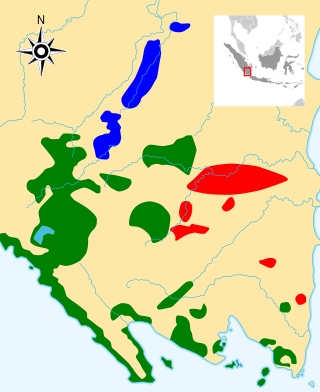

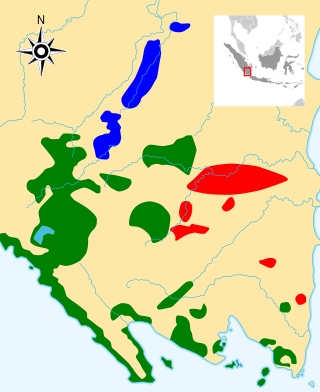

Lampung or Lampungic is an Austronesian language or dialect cluster with around 1.5 million native speakers, who primarily belong to the Lampung ethnic group of southern Sumatra, Indonesia. It is divided into two or three varieties: Lampung Api, Lampung Nyo, and Komering. The latter is sometimes included in Lampung Api, sometimes treated as an entirely separate language. Komering people see themselves as ethnically separate from, but related to, Lampung people.

Euphorbia haeleeleana, the Kauaʻi spurge, is a species of flowering plant in the croton family, Euphorbiaceae, that is endemic to the islands of Kauaʻi and Oaʻhu in Hawaii. Like other Hawaiian spurges it is known as `akoko.

Flueggea neowawraea, the mēhamehame, is a species of flowering tree in the family Phyllanthaceae, that is endemic to Hawaii. It can be found in dry, coastal mesic, and mixed mesic forests at elevations of 250 to 1,000 m. Associated plants include kukui, hame, ʻahakea, alaheʻe, olopua, hao, and aʻiaʻi. Mēhamehame was one of the largest trees in Hawaiʻi, reaching a height of 30 m (98 ft) and trunk diameter of 2 m (6.6 ft). Native Hawaiians used the extremely hard wood of this tree to make weaponry.

Acehnese or Achinese is an Austronesian language natively spoken by the Acehnese people in Aceh, Sumatra, Indonesia. This language is also spoken by Acehnese descendants in some parts of Malaysia like Yan, in Kedah. Acehnese is used as the co-official language in the province of Aceh, alongside Indonesian.

The Simeulue language is spoken by the Simeulue people of Simeulue off the western coast of Sumatra, Indonesia.

Palembang, also known as Palembang Malay, is a Malayic variety of the Musi dialect chain primarily spoken in the city of Palembang and nearby lowlands, and also as a lingua franca throughout South Sumatra. Since parts of the region used to be under direct Javanese rule for quite a long time, Palembang is significantly influenced by Javanese, down to its core vocabularies.

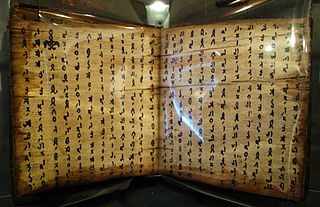

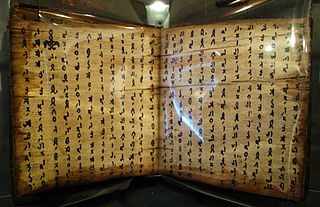

Mandailing Batak or Mandailing is an Austronesian language spoken in Sumatra, the northern island of Indonesia. It is spoken mainly in Mandailing Natal Regency, North Padang Lawas Regency, Padang Lawas Regency, and eastern parts of Labuhan Batu Regency, North Labuhan Batu Regency, South Labuhan Batu Regency and northwestern parts of Riau Province. It is written using the Latin script but historically used Batak script.

Kei is an Austronesian language spoken in a small region of the Moluccas, a province of Indonesia.

Piper retrofractum, the Balinese long pepper or Javanese long pepper, is a flowering vine in the family Piperaceae, cultivated for its fruit, which is usually dried and used as a spice and seasoning. This species is native to Java island in Indonesia.

Cyanea acuminata is a rare species of flowering plant known by the common names Honolulu cyanea. It is endemic to Oahu, where there are no more than 250 individuals remaining. It is a federally listed endangered species of the United States. Like other Cyanea it is known as haha in Hawaiian.

Banda is an Austronesian language of the Central Maluku subgroup. Along with Kei, it is one of the two languages of the Kei Islands in the Indonesian province of Maluku.

Talaud is an Austronesian language spoken on the Talaud Islands north of Sulawesi, Indonesia. There are 2 dialects, namely Lami dialect which is spoken on Miangas, Nanusa Islands, and Esang in the northern part of Karakelang Island; Tirawata dialect is used in Lirung, Kabaruan, and the southern part of Karakelang Island.

Pakpak, or Batak Dairi, is an Austronesian language of Sumatra. It is spoken in Dairi Regency, Pakpak Bharat Regency, Parlilitan district of Humbang Hasundutan Regency, Manduamas district of Central Tapanuli Regency, and Subulussalam and Aceh Singkil Regency.

One of the major human migration events was the maritime settlement of the islands of the Indo-Pacific by the Austronesian peoples, believed to have started from at least 5,500 to 4,000 BP. These migrations were accompanied by a set of domesticated, semi-domesticated, and commensal plants and animals transported via outrigger ships and catamarans that enabled early Austronesians to thrive in the islands of Maritime Southeast Asia, Near Oceania (Melanesia), Remote Oceania, Madagascar, and the Comoros Islands.