The Memnonia quadrangle is one of a series of 30 quadrangle maps of Mars used by the United States Geological Survey (USGS) Astrogeology Research Program. The Memnonia quadrangle is also referred to as MC-16.

The Noachis quadrangle is one of a series of 30 quadrangle maps of Mars used by the United States Geological Survey (USGS) Astrogeology Research Program. The Noachis quadrangle is also referred to as MC-27.

The Casius quadrangle is one of a series of 30 quadrangle maps of Mars used by the United States Geological Survey (USGS) Astrogeology Research Program. The quadrangle is located in the north-central portion of Mars’ eastern hemisphere and covers 60° to 120° east longitude and 30° to 65° north latitude. The quadrangle uses a Lambert conformal conic projection at a nominal scale of 1:5,000,000 (1:5M). The Casius quadrangle is also referred to as MC-6. Casius quadrangle contains part of Utopia Planitia and a small part of Terra Sabaea. The southern and northern borders of the Casius quadrangle are approximately 3,065 km and 1,500 km wide, respectively. The north to south distance is about 2,050 km. The quadrangle covers an approximate area of 4.9 million square km, or a little over 3% of Mars’ surface area.

The Diacria quadrangle is one of a series of 30 quadrangle maps of Mars used by the United States Geological Survey (USGS) Astrogeology Research Program. The quadrangle is located in the northwestern portion of Mars’ western hemisphere and covers 180° to 240° east longitude and 30° to 65° north latitude. The quadrangle uses a Lambert conformal conic projection at a nominal scale of 1:5,000,000 (1:5M). The Diacria quadrangle is also referred to as MC-2. The Diacria quadrangle covers parts of Arcadia Planitia and Amazonis Planitia.

The Arcadia quadrangle is one of a series of 30 quadrangle maps of Mars used by the United States Geological Survey (USGS) Astrogeology Research Program. The quadrangle is located in the north-central portion of Mars’ western hemisphere and covers 240° to 300° east longitude and 30° to 65° north latitude. The quadrangle uses a Lambert conformal conic projection at a nominal scale of 1:5,000,000 (1:5M). The Arcadia quadrangle is also referred to as MC-3.

The Mare Acidalium quadrangle is one of a series of 30 quadrangle maps of Mars used by the United States Geological Survey (USGS) Astrogeology Research Program. The quadrangle is located in the northeastern portion of Mars’ western hemisphere and covers 300° to 360° east longitude and 30° to 65° north latitude. The quadrangle uses a Lambert conformal conic projection at a nominal scale of 1:5,000,000 (1:5M). The Mare Acidalium quadrangle is also referred to as MC-4.

The Amazonis quadrangle is one of a series of 30 quadrangle maps of Mars used by the United States Geological Survey (USGS) Astrogeology Research Program. The Amazonis quadrangle is also referred to as MC-8.

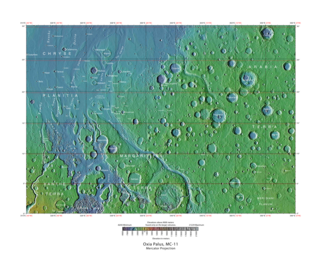

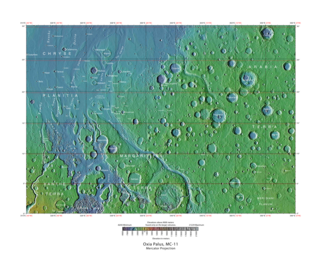

The Oxia Palus quadrangle is one of a series of 30 quadrangle maps of Mars used by the United States Geological Survey (USGS) Astrogeology Research Program. The Oxia Palus quadrangle is also referred to as MC-11.

The Phoenicis Lacus quadrangle is one of a series of 30 quadrangle maps of Mars used by the United States Geological Survey (USGS) Astrogeology Research Program. The Phoenicis Lacus quadrangle is also referred to as MC-17. Parts of Daedalia Planum, Sinai Planum, and Solis Planum are found in this quadrangle. Phoenicis Lacus is named after the phoenix which according to myth burns itself up every 500 years and then is reborn.

The Hellas quadrangle is one of a series of 30 quadrangle maps of Mars used by the United States Geological Survey (USGS) Astrogeology Research Program. The Hellas quadrangle is also referred to as MC-28 . The Hellas quadrangle covers the area from 240° to 300° west longitude and 30° to 65° south latitude on the planet Mars. Within the Hellas quadrangle lies the classic features Hellas Planitia and Promethei Terra. Many interesting and mysterious features have been discovered in the Hellas quadrangle, including the giant river valleys Dao Vallis, Niger Vallis, Harmakhis, and Reull Vallis—all of which may have contributed water to a lake in the Hellas basin in the distant past. Many places in the Hellas quadrangle show signs of ice in the ground, especially places with glacier-like flow features.

The Eridania quadrangle is one of a series of 30 quadrangle maps of Mars used by the United States Geological Survey (USGS) Astrogeology Research Program. The Eridania quadrangle is also referred to as MC-29.

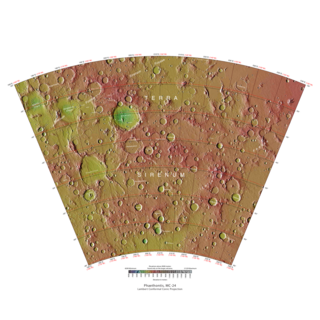

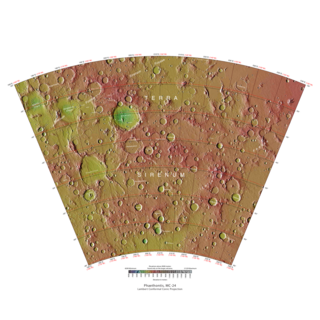

The Phaethontis quadrangle is one of a series of 30 quadrangle maps of Mars used by the United States Geological Survey (USGS) Astrogeology Research Program. The Phaethontis quadrangle is also referred to as MC-24.

The Thaumasia quadrangle is one of a series of 30 quadrangle maps of Mars used by the United States Geological Survey (USGS) Astrogeology Research Program. The Thaumasia quadrangle is also referred to as MC-25 . The name comes from Thaumas, the god of the clouds and celestial apparitions.

The Argyre quadrangle is one of a series of 30 quadrangle maps of Mars used by the United States Geological Survey (USGS) Astrogeology Research Program. The Argyre quadrangle is also referred to as MC-26. It contains Argyre Planitia and part of Noachis Terra.

The Mare Australe quadrangle is one of a series of 30 quadrangle maps of Mars used by the United States Geological Survey (USGS) Astrogeology Research Program. The Mare Australe quadrangle is also referred to as MC-30. The quadrangle covers all the area of Mars south of 65°, including the South polar ice cap, and its surrounding area. The quadrangle's name derives from an older name for a feature that is now called Planum Australe, a large plain surrounding the polar cap. The Mars polar lander crash landed in this region.

Dark slope streaks are narrow, avalanche-like features common on dust-covered slopes in the equatorial regions of Mars. They form in relatively steep terrain, such as along escarpments and crater walls. Although first recognized in Viking Orbiter images from the late 1970s, dark slope streaks were not studied in detail until higher-resolution images from the Mars Global Surveyor (MGS) and Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) spacecraft became available in the late 1990s and 2000s.

HiWish is a program created by NASA so that anyone can suggest a place for the HiRISE camera on the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter to photograph. It was started in January 2010. In the first few months of the program 3000 people signed up to use HiRISE. The first images were released in April 2010. Over 12,000 suggestions were made by the public; suggestions were made for targets in each of the 30 quadrangles of Mars. Selected images released were used for three talks at the 16th Annual International Mars Society Convention. Below are some of the over 4,224 images that have been released from the HiWish program as of March 2016.

The common surface features of Mars include dark slope streaks, dust devil tracks, sand dunes, Medusae Fossae Formation, fretted terrain, layers, gullies, glaciers, scalloped topography, chaos terrain, possible ancient rivers, pedestal craters, brain terrain, and ring mold craters.

Copernicus is a large crater on Mars, with a diameter close to 300 km. It is located south of the planet's equator in the heavily cratered highlands of Terra Sirenum in the Phaethontis quadrangle at 48.8°S and 191.2°E. Its name was approved in 1973, and it was named after Nicolaus Copernicus.

Yardangs are common in some regions on Mars, especially in the Medusae Fossae Formation. This formation is found in the Amazonis quadrangle and near the equator. They are formed by the action of wind on sand sized particles; hence they often point in the prevailing direction that the winds were blowing when they were formed. Because they exhibit very few impact craters they are believed to be relatively young. The easily eroded nature of the Medusae Fossae Formation suggests that it is composed of weakly cemented particles, and was most likely formed by the deposition of wind-blown dust or volcanic ash. Yardangs are parts of rock that have been sand blasted into long, skinny ridges by bouncing sand particles blowing in the wind. Layers are seen in parts of the formation. A resistant caprock on the top of yardangs has been observed in Viking, Mars Global Surveyor, and HiRISE photos. Images from spacecraft show that they have different degrees of hardness probably because of significant variations in the physical properties, composition, particle size, and/or cementation.