Racism in the Philippines is multifarious and emerged in various portions of the history of people, institutions and territories coinciding to that of the present-day Philippines.

Racism in the Philippines is multifarious and emerged in various portions of the history of people, institutions and territories coinciding to that of the present-day Philippines.

Racial discrimination in the Philippines has a historical foundation dating back to the Spanish colonial era (1565-1898), characterized by the implementation of a social hierarchy known as the "casta". This system favored individuals of Spanish descent, such as the "criollos" or "insulares", while relegating native Filipinos to the lowest rungs of society. The hierarchical structure entrenched during this period had enduring effects on societal dynamics, shaping power relations and perpetuating disparities based on racial heritage.

Following the Spanish colonial rule, the American colonial period (1898–1946) introduced new dynamics of racial discrimination, influenced by American cultural hegemony. This era witnessed various forms of racism, including economic exploitation, social hierarchy, and segregation. American colonial policies reinforced notions of superiority, contributing to the marginalization of indigenous Filipinos and the consolidation of power among American elites.

Despite enduring racism and oppression, Filipinos exhibited resilience and resistance, actively advocating for their rights and independence. This period of struggle culminated in the eventual end of American colonial rule and the establishment of the Philippine Republic in 1946, marking a significant milestone in the nation's journey towards self-determination.

Both colonial periods left lasting legacies of social stratification and economic exploitation. Indigenous Filipinos often found themselves disenfranchised and denied equal opportunities, while Europeans and Americans wielded disproportionate power and privilege. The exploitation of natural resources and the utilization of cheap labor further exacerbated socioeconomic inequalities, perpetuating a cycle of marginalization and subjugation.

Polls have shown that some Filipinos hold negative views directed against the Moro people due to alleged Islamic terrorism. [1] [2] [3] [4] [5]

Contact between the indigenous peoples of the islands and the Han began hundreds of years ago, predating the arrival of Westerners. Strong ties through trade and commerce sustained ancient states such as the Kingdom of Tondo. The Sultanate of Sulu also has significant relationship with the Ming dynasty whereas its leader Paduka Batara, granted the only foreign monument in China, was sent with his sons to pay tribute to Emperor Yung Lo. [6] [7] Despite years of contact, the rift between the two groups emerged at the height of the Spanish colonization.

After the destructive raids of various ports and towns including the newly Spanish-established Manila by Chinese pirate Limahong, the colonial government saw the Chinese as a threat and decided to curb the Sangley in the colony by ethnic segregation and immigration control. Assimilation by conversion to Catholicism was also enforced by the governor-general Gómez Pérez Dasmariñas in the late 16th century. Only Catholic Sangleys, Indio wives and their Mestizo de Sangley children were granted land such as in Parían and nearby Binondo. However, these measures to attain racial control were seen to be difficult to achieve. As a result, four massacres, the first happening in 1603, and expulsions ensued against unconverted Sangleys. [8] Other ethnic-motivated incidents were during the massacre of Sangleys as a retaliation to Koxinga's raids of several towns in Luzon during 1662. This resulted in a failed invasion. It was said that although the ethnic Chinese in the island themselves distanced from the military leader, anti-Chinese sentiments among locals grew and led to killings in the Manila area. [9] Another event is after the 1762 British occupation of Manila amidst the Seven Years' War. As the Spanish, who regained control of invaded Manila and nearby port province of Cavite, many non-natives specifically Spanish, Mestizos, Chinese, and Indians were imprisoned for supporting the British.

The Spanish colonial government imposed legislation on the ethnic Chinese, which were viewed unfavorably. Such laws were meant to Christianize the ethnic Chinese, aid them assimilate into mainstream Philippine society and to encourage them to take up farming. The Chinese were viewed as an economic, political and socio-religious threat to the small Spaniard colonial population in Spanish Philippines. [10]

As part of the phenomenon of transculturation and acculturation in the modern Chinese Filipino community as an integrated minority group in Philippine society, some level of endogamy and self-segregation is also present stemming from concerns of protecting and preserving the cultural identity and cultural heritage of the group as part of its cultural rights on the basis of cultural conservatism to prevent and resist complete cultural assimilation and ethnocide, wherein some would refuse to marry Filipinos without Chinese descent. For younger generations in the Philippines, this phenomenon is called "The Great Wall" in reference to the Great Wall of China, as a euphemism to describe the social barriers used to prevent outside forces from entering and supplanting the culture. In this case, it is used to prevent Filipinos without Chinese descent from entering the Chinese Filipino family through interethnic marriage due to fears of complete assimilation of the family's cultural identity to the society's dominant cultures. Due to these fears and concerns, some Filipinos without Chinese descent who wish to enter into the Chinese Filipino community is said to have to "climb the Great Wall" in order to cross this social barrier and so, feel diminished and excluded from these barriers that prevent the dominant culture from completely subsuming the Chinese Filipino community.

The rights of the Philippines highland groups are legally protected under Indigenous Peoples' Rights Act (IPRA) which is cited as the first of its kind in Southeast Asia. The law enabled them to acquire titles to their ancestral domains. However the highlanders continue to experience some degree of discrimination and are described by cultural anthropologist Nestor Castro that "They still cannot identify with the so-called mainstream society or culture." Highlanders particularly experience marginalization in urban areas such as in Manila. [11]

Ethnic divide among highland tribes [ broken anchor ] began from the conception of a Philippine state notably during the Commonwealth of the Philippines.[ citation needed ]In order to actualize the dream of a unified Philippine identity,[ citation needed ] the said Commonwealth government established the Institute of National Language (Filipino: Surian ng Wikang Pambansâ) which adopted Tagalog as the baseline for the national language.

Demography of the Philippines records the human population, including its population density, ethnicity, education level, health, economic status, religious affiliations, and other aspects. The Philippines annualized population growth rate between the years 2015–2020 was 1.53%. According to the 2020 census, the population of the Philippines is 109,033,245. The first census in the Philippines was held in the year 1591 which counted 667,612 people.

Mestizo is a person of mixed European and Indigenous American ancestry in the former Spanish Empire. In certain regions such as Latin America, it may also refer to people who are culturally European even though their ancestors were Indigenous. The term was used as an ethno-racial exonym for mixed-race castas that evolved during the Spanish Empire. It was a formal label for individuals in official documents, such as censuses, parish registers, Inquisition trials, and others. Priests and royal officials might have classified persons as mestizos, but individuals also used the term in self-identification. With the Bourbon reforms and the independence of the Americas, the caste system disappeared and terms like "mestizo" fell in popularity.

Casta is a term which means "lineage" in Spanish and Portuguese and has historically been used as a racial and social identifier. In the context of the Spanish Empire in the Americas, the term also refers to a now-discredited 20th-century theoretical framework which postulated that colonial society operated under a hierarchical race-based "caste system". From the outset, colonial Spanish America resulted in widespread intermarriage: unions of Spaniards, indigenous people, and Africans. Basic mixed-race categories that appeared in official colonial documentation were mestizo, generally offspring of a Spaniard and an Indigenous person; and mulatto, offspring of a Spaniard and an African. A plethora of terms were used for people with mixed Spanish, Indigenous, and African ancestry in 18th-century casta paintings, but they are not known to have been widely used officially or unofficially in the Spanish Empire.

Chinese Filipinos are Filipinos of Chinese descent with ancestry mainly from Fujian, but are typically born and raised in the Philippines. Chinese Filipinos are one of the largest overseas Chinese communities in Southeast Asia.

Binondo is a district in Manila and is referred to as the city's Chinatown. Its influence extends beyond to the places of Quiapo, Santa Cruz, San Nicolas and Tondo. It is the oldest Chinatown in the world, established in 1594 by the Spaniards as a settlement near Intramuros but across the Pasig River for Catholic Chinese; it was positioned so that the colonial administration could keep a close eye on their migrant subjects. It was already a hub of Chinese commerce even before the Spanish colonial period. Binondo is the center of commerce and trade of Manila, where all types of business run by Chinese Filipinos thrive.

Sangley and Mestizo de Sangley are archaic terms used in the Philippines during the Spanish colonial era to describe respectively a person of pure overseas Chinese ancestry and a person of mixed Chinese and native Filipino ancestry. The Sangley Chinese were ancestors to both modern Chinese Filipinos and modern Filipino mestizo descendants of the Mestizos de Sangley, also known as Chinese mestizos, which are mixed descendants of Sangley Chinese and native Filipinos. Chinese mestizos were mestizos in the Spanish Empire, classified together with other Filipino mestizos.

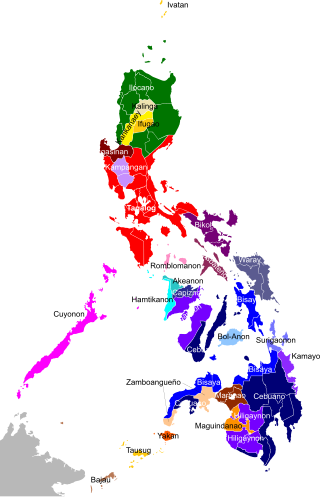

Filipinos are citizens or people identified with the country of the Philippines. The majority of Filipinos today are predominantly Catholic and come from various Austronesian peoples, all typically speaking Tagalog, English, or other Philippine languages. Despite formerly being subject to Spanish colonialism, only around 2–4% of Filipinos are fluent in Spanish. Currently, there are more than 185 ethnolinguistic groups in the Philippines each with its own language, identity, culture, tradition, and history.

The Philippines is inhabited by more than 182 ethnolinguistic groups, many of which are classified as "Indigenous Peoples" under the country's Indigenous Peoples' Rights Act of 1997. Traditionally-Muslim peoples from the southernmost island group of Mindanao are usually categorized together as Moro peoples, whether they are classified as Indigenous peoples or not. About 142 are classified as non-Muslim Indigenous people groups, and about 19 ethnolinguistic groups are classified as neither Indigenous nor Moro. Various migrant groups have also had a significant presence throughout the country's history.

Philippine Hokkien is a dialect of the Hokkien language of the Southern Min branch of Min Chinese descended directly from Old Chinese of the Sinitic family, primarily spoken vernacularly by Chinese Filipinos in the Philippines, where it serves as the local Chinese lingua franca within the overseas Chinese community in the Philippines and acts as the heritage language of a majority of Chinese Filipinos. Despite currently acting mostly as an oral language, Hokkien as spoken in the Philippines did indeed historically have a written language and is actually one of the earliest sources for written Hokkien using both Chinese characters as early as around 1587 or 1593 through the Doctrina Christiana en letra y lengua china and using the Latin script as early as the 1590s in the Boxer Codex and was actually the earliest to systematically romanize the Hokkien language throughout the 1600s in the Hokkien-Spanish works of the Spanish friars especially by the Dominican Order, such as in the Dictionario Hispanico Sinicum (1626-1642) and the Arte de la Lengua Chiõ Chiu (1620) among others. The use of Hokkien in the Philippines was historically influenced by Philippine Spanish, Filipino (Tagalog) and Philippine English. As a lingua franca of the overseas Chinese community in the Philippines, the minority of Chinese Filipinos of Cantonese and Taishanese descent also uses Philippine Hokkien for business purposes due to its status as "the Chinoy business language" [sic]. It is also used as a liturgical language as one of the languages that Protestant Chinese Filipino churches typically minister in with their church service, which they sometimes also minister to students in Chinese Filipino schools that they also usually operate. It is also a liturgical language primarily used by Chinese Buddhist, Taoist, and Matsu veneration temples in the Philippines, especially in their sutra chanting services and temple sermons by monastics.

In the Philippines, Filipino Mestizo, or colloquially Tisoy, is a name used to refer to people of mixed native Filipino and any foreign ancestry. The word mestizo itself is of Spanish origin; it was first used in the Americas to describe people of mixed Amerindian and European ancestry. Currently and historically, the Chinese mestizos were and are still ordinarily the most populous subgroup among mestizos; they have historically been very influential in the creation of Filipino nationalism. The Spanish mestizos also historically and currently exist as a smaller population, but remain a significant minority among mestizos which historically enjoyed prestigious status in Philippine society during Spanish colonial times.

The Ilustrados constituted the Filipino intelligentsia during the Spanish colonial period in the late 19th century. Elsewhere in New Spain, the term gente de razón carried a similar meaning.

Spanish Filipino or Hispanic Filipino are an ethnic and a multilingualistic group of Spanish descent, Spanish-speaking and Spanish cultured individuals and their descendance native to Spain, Mexico, the United States, Latin America and the Philippines. They consist of local and overseas citizens from another country that includes Peninsulares, Insulares or White Criollos, Mestizos and people via South America who are descendants of the original Spanish settlers during the Spanish colonial period, or Hispanicized Filipino natives who may practice Spanish culture, who form part of the Spanish diaspora worldwide and who may or may not speak the Spanish language.

Immigration to the Philippines is the process by which people migrate to the Philippines to reside in the country. Many, but not all, become citizens of the Philippines.

Racism in Mexico refers to the social phenomenon in which behaviors of discrimination, prejudice, and any form of antagonism are directed against people in that country due to their race, ethnicity, skin color, language, or physical complexion. It may also refer to the treatment and sense of superiority of one race over another.

There is no single system of races or ethnicities that covers all modern Latin America, and usage of labels may vary substantially.

Asian Mexicans are Mexicans of Asian descent. Asians are considered cuarta raíz of Mexico in conjunction with the two main roots: Native and European, and the third African root.

Tipos del País, literally meaning Types of the Country, is a Filipino Miniature painting of watercolor method that shows the different types of inhabitants in the Philippines in their different native costumes that show their social status and occupation during colonial times.

The post-1500s Philippines is defined by colonial powers occupying the land. Whether it be the Spanish, the Americans, or the Japanese, the Philippines were subjugated and shaped by the presence of a hegemonic power enacting dominance over the people, the land, and the culture itself. The respective field of the archaeology of the post-1500s Philippines is a particularly growing and revolutionary field, particularly seen in the archaeology of Stephen Acabado in Ifugao and Grace Barretto-Tesoro in Manila. There were also many important events that had happened during this period. In 1521, Portuguese explorer, Ferdinand Magellan discovered Homonhon Island and called it "Arcigelago de San Lazaro." Magellan became the first European to cross over the Pacific Ocean.

Fernando Nakpil Zialcita is a Filipino anthropologist and cultural historian. His areas of specialization are in heritage and identity; art and its cultural context; and interfaces between the foreign and the indigenous.

In the terminology of linguistic anthropology, linguistic racism, both spoken and written, is a mechanism that perpetuates discrimination, marginalization, and prejudice customarily based on an individual or community's linguistic background. The most evident manifestation of this kind of racism is racial slurs; however, there are covert forms of it. Linguistic racism also relates to the concept of "racializing discourses," which is defined as the ways race is discussed without being explicit but still manages to represent and reproduce race. This form of racism acts to classify people, places, and cultures into social categories while simultaneously maintaining this social inequality under a veneer of indirectness and deniability.