Provinces are the first-level administrative divisions of Indonesia. It is formerly called the first-level provincial region before the Reform era. Provinces have a local government, consisting of a governor and a regional legislative body. The governor and members of local representative bodies are elected by popular vote for five-year terms, but governors can only serve for two terms. Provincial governments have the authority to regulate and manage their own government affairs, subject to the limits of the central government. The average land area of all 38 provinces in Indonesia is about 49,800 km2 (19,200 sq mi), and they had an average population in mid 2023 of 7,334,111 people.

In Indonesia, village or subdistrict is the fourth-level subdivision and the smallest administrative division of Indonesia below a district, regency/city, and province. Similar administrative divisions outside of Indonesia include barangays in the Philippines, Muban in Thailand, civil townships and incorporated municipalities in the United States and Canada, communes in France and Vietnam, dehestan in Iran, hromada in Ukraine, Gemeinden in Germany, comuni in Italy, or municipios in Spain. The UK equivalent are civil parishes in England and communities in Wales. There are a number of names and types for villages in Indonesia, with desa being the most frequently used for regencies, and kelurahan for cities or for those communities within regencies which have town characteristics. According to the 2019 report by the Ministry of Home Affairs, there are 8,488 urban villages and 74,953 rural villages in Indonesia. North Aceh Regency contained the highest number of rural villages (852) amongst all of the regencies of Indonesia, followed by Pidie Regency with 730 rural villages and Bireuen Regency with 609 rural villages. Prabumulih, with only 12 rural villages, contained the fewest. Counted together, the sixteen regencies of Indonesia containing the most rural villages—namely, North Aceh (852), Pidie (730), Bireuen (609), Aceh Besar (604), Tolikara (541), East Aceh (513), Yahukimo (510), Purworejo (469), Lamongan (462), South Nias (459), Kebumen (449), Garut (421), Bojonegoro (419), Bogor (416), Cirebon (412), and Pati (401)—contain one-third of all the rural villages in Indonesia. Five of these are located in Aceh, two in Highland Papua, three in Central Java, two in East Java, three in West Java, and one in North Sumatra. An average number of rural villages in the regencies and 15 cities of Indonesia is 172 villages. A village is the lowest administrative division in Indonesia, and it is the lowest of the four levels. The average land area of villages in Indonesia is about 25.41 km2 (9.81 sq mi), while its average population is about 3,723 people.

Sukabumi Regency is a regency (kabupaten) in southwestern Java, as part of West Java province of Indonesia. The regency seat is located in Palabuhan Ratu, a coastal district facing the Indian Ocean. The regency fully encircles the administratively separated city of Sukabumi. Covering an area of 4,164.15 km2, the regency is the largest regency in West Java and the second largest regency on Java after the Banyuwangi Regency in East Java. The regency had a population of 2,341,409 at the 2010 census and 2,725,450 at the 2020 census; the official estimate as at mid 2023 was 2,802,404, with a large proportion of it living in the northeastern part of the regency that encircles Sukabumi City, south of Mount Gede. A plan to create a new regency, the putative North Sukabumi Regency, was considered by the Indonesian government in 2013, but has been deferred until the end of the current morotorium on new creations of regencies.

The Bantenese are an Austronesian ethnic group native to Banten in the westernmost part of Java island, Indonesia. The area of Banten province corresponds more or less with the area of the former Banten Sultanate, a Bantenese nation state that preceded Indonesia. In his book "The Sultanate of Banten", Guillot Claude writes on page 35: “These estates, owned by the Bantenese of Chinese descent, were concentrated around the village of Kelapadua.” Most of Bantenese are Sunni Muslim. The Bantenese speak the Sundanese-Banten dialect, a variety of the Sundanese language which does not have a general linguistic register, this language is called Basa Sunda Banten.

Sri Baduga Maharaja or Sang Ratu Jayadewata was the great king of the Hindu Sunda kingdom in West Java, reigned 1482 to 1521 from his capital in Pakuan Pajajaran. He brought his kingdom greatness and prosperity.

Merigi is a district (kecamatan) of Kepahiang Regency, Bengkulu, Indonesia.

The Ministry of Home Affairs is an interior ministry of the government of Indonesia responsible for matters of the state. The ministry was formerly known as the Department of Home Affairs until 2010 when the nomenclature of the Department of Home Affairs was changed to the Ministry of Home Affairs in accordance with the Regulation of the Minister of Home Affairs Number 3 of 2010 on the Nomenclature of the Ministry of Home Affairs.

Minahasa Regency is a regency in North Sulawesi, Indonesia. Its capital is Tondano. It covers an area of 1,141.64 km2 and had a population of 310,384 at the 2010 Census; this rose to 347,290 at the 2020 Census, and the official estimate as at mid 2023 was 351,920.

Gorontalo people, also known as Gorontalese, are a native ethnic group and the most populous ethnicity in the northern part of Sulawesi. The Gorontalo people have traditionally been concentrated in the provinces of Gorontalo, North Sulawesi, and the northern part of Central Sulawesi.

Sumedang Larang is an Islamic Kingdom based in Sumedang, West Java. Its territory consisted of the Parahyangan region, before becoming a vassal state under the Mataram Sultanate.

The Lampung or Lampungese are an indigenous ethnic group native to Lampung and some parts of South Sumatra, Bengkulu, as well as in the southwest coast of Banten. They speak the Lampung language, a Lampungic language estimated to have 1.5 million speakers.

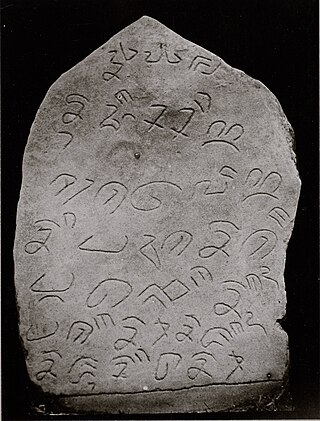

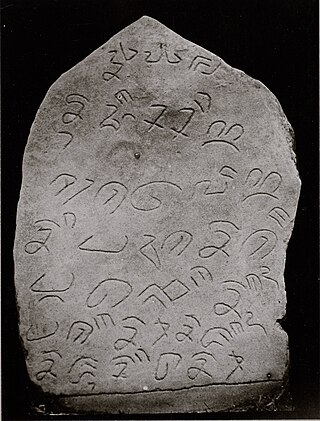

Ciaruteun inscription also written Ciarutön or also known as Ciampea inscription is a 5th-century stone inscription discovered on the riverbed of Ciaruteun River, a tributary of Cisadane River, not far from Bogor, West Java, Indonesia. The inscription is dated from the Tarumanagara kingdom period, one of the earliest Hindu kingdoms in Indonesian history. The inscription states King Purnawarman is the ruler of Tarumanagara.

Banten Sundanese or Bantenese is one of the Sundanese dialects spoken predominantly by the Bantenese — an indigenous ethnic group native to Banten — in the westernmost region of the island of Java, and in the western Bogor Regency, as well as the northwestern parts of Sukabumi Regency. A variety of Bantenese is spoken by the Ciptagelar people in the Kasepuhan Ciptagelar traditional community in the Cisolok district and the Kasepuhan Banten Kidul traditional community in the Lebak Regency.

Bungku people are an ethnic group who mostly resides in North Bungku, South Bungku, Central Bungku, and Menui Islands districts di Morowali Regency, in Central Sulawesi province of Indonesia. This ethnic group is divided into several sub-groups, namely Lambatu, Epe, Ro'tua, Reta, and Wowoni. Bungku people have their own language, called Bungku language, which is one of their characteristic and serves as a means of communication between themselves. They generally embrace Islam or Christianity.

In Indonesian law, the term "city" is generally defined as the second-level administrative subdivision of the Republic of Indonesia, an equivalent to regency. The difference between a city and a regency is that a city has non-agricultural economic activities and a dense urban population, while a regency comprises predominantly rural areas and is larger in area than a city. However, Indonesia historically had several classifications of cities.

The Regent of Thousand Islands, officially the Administrative Regent of Thousand Islands, is the highest office in the regency of Thousand Islands. Unlike regents in other regencies in Indonesia, the regent is appointed directly by the governor. The regency has no regional parliament, thus making the regent responsible to the governor.

Old Sundanese is the earliest recorded stage of the Sundanese language which is spoken in the western part of Java, Indonesia. The evidence is recorded in inscriptions from around the 12th to 14th centuries and ancient palm-leaf manuscripts from the 15th to 17th centuries AD. Old Sundanese is no longer used today, but has developed into its descendant, modern Sundanese.

Cirebon Sundanese is a variety of conversation in Sundanese in the ex-Residency of Cirebon and its surroundings, which includes Kuningan, Majalengka, Cirebon, Indramayu and Subang as well as Brebes in Central Java.

Aloysius Sartono Kartodirdjo was an Indonesian historian. A pioneer in Indonesia's postcolonial historiography, he was and is considered one of the most influential historians in the country.

Rumah Panggung is one type of traditional Betawi house whose floor is raised from the ground using wooden poles. This house is different from a Rumah Darat that sticks to the ground. Betawi houses on stilts are built in coastal areas with the aim of dealing with floods or tides. Meanwhile, stilt houses located on the banks of rivers such as in Bekasi are not only built to avoid flooding, but also for safety from wild animals.