| Part of a series on |

| Buddhism |

|---|

|

In Buddhism, sentient beings or living beings are beings with consciousness, sentience, or in some contexts life itself. [1]

| Part of a series on |

| Buddhism |

|---|

|

In Buddhism, sentient beings or living beings are beings with consciousness, sentience, or in some contexts life itself. [1]

Getz (2004: p. 760) provides a generalist Western Buddhist encyclopedic definition:

Sentient beings is a term used to designate the totality of living, conscious beings that constitute the object and audience of Buddhist teaching. Translating various Sanskrit terms (jantu, bahu jana, jagat, sattva), sentient beings conventionally refers to the mass of living things subject to illusion, suffering, and rebirth (saṃsāra). Less frequently, sentient beings as a class broadly encompasses all beings possessing consciousness, including Buddhas and Bodhisattvas.

Sentient beings are composed of the five aggregates (skandhas): matter, sensation, perception, mental formations and consciousness. In the Samyutta Nikaya , the Buddha is recorded as saying that "just as the word 'chariot' exists on the basis of the aggregation of parts, even so the concept of 'being' exists when the five aggregates are available." [2]

Early Buddhist sources classify sentient beings into five categories—divinities, humans, animals, tormented spirits, and denizens of hell—although sometimes the classification adds another category of beings called asuras between divinities and humans. [1]

While distinctions in usage and potential subdivisions or classes of sentient beings vary from one school, teacher, or thinker to another, it principally refers to beings in contrast with buddhahood. That is, sentient beings are characteristically not awakened, and are thus confined to the death, rebirth, and dukkha (suffering) characteristic of saṃsāra. [3] Thus, Dōgen writes "Those who greatly enlighten illusion are Buddhas; those who have great illusion in enlightenment are sentient beings." [4]

However, Mahayana Buddhism also simultaneously teaches that sentient beings also contain Buddha-nature—the intrinsic potential to transcend the conditions of saṃsāra and attain enlightenment, thereby obtaining Buddhahood. [5] Thus, in Mahayana, it is to sentient beings that the bodhisattva vow of compassion is pledged and sentient beings are the object of the all inclusive great compassion (maha karuna) and skillful means (upaya) of the Buddhas.

Furthermore, in East Asian Buddhism, all beings (including plant life and even inanimate objects or entities considered "spiritual" or "metaphysical" by conventional Western thought) are or may be considered beings with Buddha-nature. [6] [7] The idea that "inanimate" beings have Buddha nature was defended by Zhanran (711–782) of the Tiantai school as well as Japanese figures like Kūkai and Dōgen. [8]

In Buddhism, a bodhisattva or bodhisatva is a person who is on the path towards bodhi ('awakening') or Buddhahood.

Buddhist philosophy is the ancient Indian philosophical system that developed within the religio-philosophical tradition of Buddhism. It comprises all the philosophical investigations and systems of rational inquiry that developed among various schools of Buddhism in ancient India following the parinirvāṇa of Gautama Buddha, as well as the further developments which followed the spread of Buddhism throughout Asia.

In Buddhism, Buddha is a title for those who are spiritually awake or enlightened, and have thus attained the supreme goal of Buddhism, variously described as pristine awareness, nirvana, awakening, enlightenment, and liberation or vimutti. A Buddha is also someone who has fully understood the Dharma, the true nature of things or the universal law of phenomena. Buddhahood is the condition and state of a buddha. This highest spiritual state of being is also termed sammā-sambodhi and is interpreted in many different ways across schools of Buddhism.

Tiantai or T'ien-t'ai is an East Asian Buddhist school of Mahāyāna Buddhism that developed in 6th-century China. Tiantai Buddhism emphasizes the "One Vehicle" (Ekayāna) doctrine derived from the Lotus Sūtra as well as Mādhyamaka philosophy, particularly as articulated in the works of the 4th patriarch Zhiyi. Brook Ziporyn, professor of ancient and medieval Chinese religion and philosophy, states that Tiantai Buddhism is "the earliest attempt at a thoroughgoing Sinitic reworking of the Indian Buddhist tradition." According to Paul Swanson, scholar of Buddhist studies, Tiantai Buddhism grew to become "one of the most influential Buddhist traditions in China and Japan."

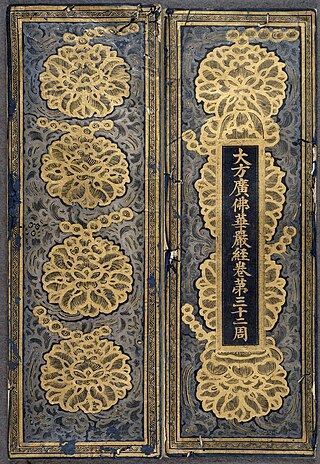

The Buddhāvataṃsaka-nāma-mahāvaipulya-sūtra is one of the most influential Mahāyāna sutras of East Asian Buddhism. It is often referred to in short as the Avataṃsaka Sūtra. In Classical Sanskrit, avataṃsaka means garland, wreath, or any circular ornament, such as an earring. Thus, the title may be rendered in English as A Garland of Buddhas, Buddha Ornaments, or Buddha's Garland. In Buddhist Hybrid Sanskrit, the term avataṃsaka means "a great number," "a multitude," or "a collection." This is matched by the Tibetan title of the sutra, which is A Multitude of Buddhas.

The Lotus Sūtra is one of the most influential and venerated Buddhist Mahāyāna sūtras. It is the main scripture on which the Tiantai along with its derivative schools, the Japanese Tendai and Nichiren, Korean Cheontae, and Vietnamese Thiên Thai schools of Buddhism were established. It is also influential for other East Asian Buddhist schools, such as Zen. According to the British Buddhologist Paul Williams, "For many Buddhists in East Asia since early times, the Lotus Sūtra contains the final teaching of Shakyamuni Buddha—complete and sufficient for salvation." The American Buddhologist Donald S. Lopez Jr. writes that the Lotus Sūtra "is arguably the most famous of all Buddhist texts," presenting "a radical re-vision of both the Buddhist path and of the person of the Buddha."

The Tathāgatagarbha sūtras are a group of Mahayana sutras that present the concept of the "womb" or "embryo" (garbha) of the tathāgata, the buddha. Every sentient being has the possibility to attain Buddhahood because of the tathāgatagarbha.

Yāna refers to a mode or method of spiritual practice in Buddhism. It is claimed they were all taught by the Gautama Buddha in response to the various capacities of individuals. On an outwardly conventional level, the teachings and practices may appear contradictory, but ultimately they all have the same goal.

In Mahayana Buddhism, bodhicitta is the mind (citta) that is aimed at awakening (bodhi), with wisdom and compassion for the benefit of all sentient beings.

In Buddhist philosophy and soteriology, Buddha-nature is the innate potential for all sentient beings to become a Buddha or the fact that all sentient beings already have a pure Buddha-essence within themselves. "Buddha-nature" is the common English translation for several related Mahāyāna Buddhist terms, most notably tathāgatagarbha and buddhadhātu, but also sugatagarbha, and buddhagarbha. Tathāgatagarbha can mean "the womb" or "embryo" (garbha) of the "thus-gone one" (tathāgata), and can also mean "containing a tathāgata". Buddhadhātu can mean "buddha-element", "buddha-realm", or "buddha-substrate".

Buddhism includes a wide array of divine beings that are venerated in various ritual and popular contexts. Initially they included mainly Indian figures such as devas, asuras and yakshas, but later came to include other Asian spirits and local gods. They range from enlightened Buddhas to regional spirits adopted by Buddhists or practiced on the margins of the religion.

The Mahāyāna Mahāparinirvāṇa Sūtra or Nirvana Sutra for short, is an influential Mahāyāna Buddhist scripture of the Buddha-nature class. The original title of the sutra was Mahāparinirvāṇamahāsūtra and the earliest version of the text was associated with the Mahāsāṃghika-Lokottaravāda school. The sutra was particularly important for the development of East Asian Buddhism.

The ten realms, sometimes referred to as the ten worlds, are part of the belief of some forms of Buddhism that there are 240 conditions of life which sentient beings are subject to, and which they experience from moment to moment. The popularization of this term is often attributed to the Chinese scholar Chih-i who spoke about the "co-penetration of the ten worlds."

The Ādi-Buddha is the First Buddha or the Primordial Buddha. Another common term for this figure is Dharmakāya Buddha.

The Trikāya is a fundamental Mahayana Buddhist doctrine that explains the multidimensional nature of Buddhahood. As such, the Trikāya is the basic theory of Mahayana Buddhist Buddhology.

In Buddhism, an Arhat or Arahant is one who has gained insight into the true nature of existence and has achieved Nirvana and has been liberated from the endless cycle of rebirth.

Mahāyāna is a term for a broad group of Buddhist traditions, texts, philosophies, and practices developed in ancient India. It is considered one of the three main existing branches of Buddhism, the others being Theravāda and Vajrayāna. Mahāyāna accepts the main scriptures and teachings of early Buddhism but also recognizes various doctrines and texts that are not accepted by Theravada Buddhism as original. These include the Mahāyāna sūtras and their emphasis on the bodhisattva path and Prajñāpāramitā. Vajrayāna or Mantra traditions are a subset of Mahāyāna which makes use of numerous tantric methods Vajrayānists consider to help achieve Buddhahood.

Zen has a rich doctrinal background, despite the traditional Zen narrative which states that it is a "special transmission outside scriptures" which "did not stand upon words."

Original enlightenment or innate awakening is an East Asian Buddhist doctrine often translated as "inherent", "innate", "intrinsic" or "original" awakeness.

Nirmāṇakāya is the third aspect of the trikāya and the physical manifestation of a Buddha in time and space. In Vajrayāna it is described as "the dimension of ceaseless manifestation."

In Buddhism, t'i [體] is regarded as the fundamentally enlightened Buddha-mind that is present in all beings, whereas yung [用] is the manifestation of that mind in actual practice--whether it be a full manifestation (enlightened Buddha) or limited manifestation (ignorant sentient being).

In the traditional Tibetan view... the animate and inanimate phenomena of this world are charged with being, life, and spiritual vitality. These are conceived in terms of various spirits, ancestors, demigods, demons, and so on. One of the ways Tibetans recognize a spirit is through the energy that collects in a perceptual moment. A crescendo of energetic "heat" given off by something indicates a spirit. It is something like when we might say that a rock, a tree, or a cloud formation is "striking" or "dramatic" or "compelling." A rock outcropping that has a strange and arresting shape, that perhaps seems strong and menacing, will indicate the existence of some kind of non-human presence. Likewise, a hollow in a grove of trees where a spring flows and the flora are unusually lush and abundant, that has a particularly inviting and nurturing atmosphere, will likewise present itself as the home of a spirit. The unusual behavior of a natural phenomenon or an animal will suggest the same as will the rain that ends a drought or the sudden irruption of an illness.