The Continuation War, also known as the Second Soviet-Finnish War, was a conflict fought by Finland and Nazi Germany against the Soviet Union during World War II. It began with a Finnish declaration of war and invasion on 25 June 1941 and ended on 19 September 1944 with the Moscow Armistice. The Soviet Union and Finland had previously fought the Winter War from 1939 to 1940, which ended with the Soviet failure to conquer Finland and the Moscow Peace Treaty. Numerous reasons have been proposed for the Finnish decision to invade, with regaining territory lost during the Winter War regarded as the most common. Other justifications for the conflict include Finnish President Risto Ryti's vision of a Greater Finland and Commander-in-Chief Carl Gustaf Emil Mannerheim's desire to annex East Karelia.

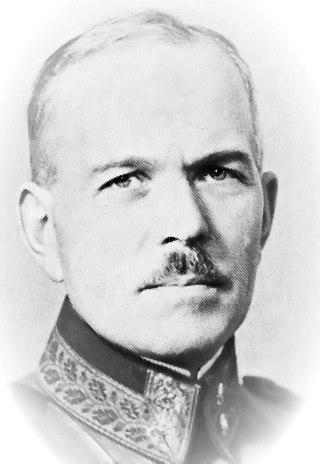

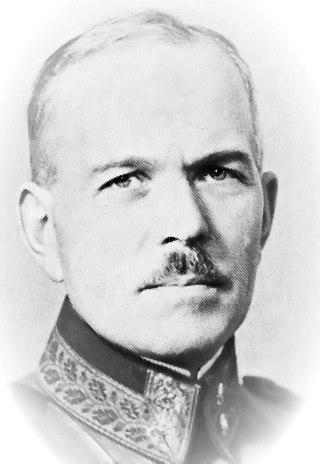

Paavo Juho Talvela was a Finnish general of the infantry, Knight of the Mannerheim Cross and a member of the Jäger movement. He participated in the Eastern Front of World War I, the Finnish Civil War, the Finnish Kinship Wars, the Winter War and the Continuation War.

Ernst Ruben Lagus, better known as Ruben Lagus, was a Finnish major general, a member of the Jäger Movement and the recipient of the first Mannerheim Cross. He participated in the Eastern Front of World War I as a volunteer of the 27th Royal Prussian Jäger Battalion, in the Finnish Civil War as battalion commander and as a supply officer in the Winter War. During the Continuation War, he commanded an armoured brigade, later division, which had a significant role in the influential Battle of Tali-Ihantala.

Karl Lennart Oesch was one of Finland's leading generals during World War II. He held a string of high staff assignments and front commands, and at the end of the Continuation War commanded three Finnish army corps on the Karelian Isthmus. He received numerous awards, including the Finnish Mannerheim Cross during his service. Following the end of the Continuation War, he was tried and convicted for war crimes relating to the treatment of Soviet prisoners-of-war.

The 6th Division was a unit of the Finnish Army during the Continuation War. Subordinated to the German XXXVI Corps, the division took part in the German-led Operation Arctic Fox in 1941. In 1943, the division was moved to Eastern Karelia, from where it was moved to the Karelian Isthmus following the start of the 1944 Soviet Vyborg–Petrozavodsk offensive. Following the Moscow armistice, the division also took part in the Lapland War against the German forces remaining in Finnish Lapland.

The 3rd Division was a unit of the Finnish Army during the Continuation War. It initially fought in the northern Finland, participating in the Finno-German Operation Arctic Fox. In 1944, it was transferred to the Karelian Isthmus to defend against the Soviet Vyborg–Petrozavodsk offensive. Following the Moscow Armistice in 1944, the division was moved to Oulu and participated in the Lapland War.

Finland participated in the Second World War initially in a defensive war against the Soviet Union, followed by another, this time offensive, war against the Soviet Union acting in concert with Nazi Germany and then finally fighting alongside the Allies against Germany.

The Shelling of Mainila, or the Mainila incident, was a military incident on 26 November 1939 in which the Soviet Union's Red Army shelled the Soviet village of Mainila near Beloostrov. The Soviet Union declared that the fire originated from Finland across the nearby border and claimed to have had losses in personnel. Through that false flag operation, the Soviet Union gained a great propaganda boost and a casus belli for launching the Winter War four days later.

There were two waves of the Finnish prisoners of war in the Soviet Union during World War II: POWs during the Winter War and the Continuation War.

The background of the Winter War covers the period before the outbreak of the Winter War between Finland and the Soviet Union (1939–1940), which stretches from the Finnish Declaration of Independence in 1917 to the Soviet-Finnish negotiations in 1938–1939.

7th Division was a Finnish Army division in the Continuation War. The division was formed Savo-Karjala military province from the men in Pohjois-Savo and Pohjois-Karjala civil guard districts.

The aftermath of the Winter War covers the historical events and views following the Winter War between Finland and the Soviet Union from 30 November 1939 to 13 March 1940.

Taavetti Laatikainen was a Finnish General of Infantry and a member of the Jäger movement. He fought in the Eastern Front of World War I, the Finnish Civil War, the Winter War and the Continuation War. During the last of these, he was awarded the Mannerheim Cross of Liberty 2nd Class. Before the Winter War, he commanded both the Reserve Officer School and the Officer Cadet School. He retired in 1948 from the position of Inspector of Infantry.

Einar Nikolai Mäkinen was a Finnish lieutenant general and a member of the Jäger movement. He participated in the Eastern Front of World War I, the Finnish Civil War, the Winter War and the Continuation War. Before the Continuation War, he participated in negotiations with the Germans regarding plans for the war.

The II Corps was a unit of the Finnish Army during the Continuation War. During the war the corps participated in combat first northwest of Lake Ladoga and on the Karelian Isthmus before moving to the Povenets–Lake Segozero region by late 1941. During the Soviet offensive of 1944, the corps conducted a fighting retreat to the region of Ilomantsi, with parts of its forces participating in the subsequent Battle of Ilomantsi.

The IV Corps was a unit of the Finnish Army during the Continuation War. During the 1941 Finnish invasion of the Karelian Isthmus, it encircled three Soviet divisions in the area south of Vyborg before being renamed as Isthmus Group.

The V Corps was a unit of the Finnish Army during the Continuation War of 1941–1944. It was first active for a brief time in 1941, and was reactivated in 1942 in the Svir sector during the trench warfare phase of the war. Following the Soviet Vyborg–Petrozavodsk offensive, the corps was moved to the Karelian Isthmus, where it fought in the Battle of Vyborg Bay, stopping a Soviet amphibious operation to cross the Vyborg Bay.

The VI Corps was a corps of the Finnish Army during the Continuation War of 1941 to 1944, where the Finnish Army fought alongside Germans against the Soviet Union. The unit was formed during a reorganization of other Finnish army corps on 29 June 1941, prior to the start of Finnish offensive operations on the night of 9–10 July.

Aarne Leopold Blick was a Finnish lieutenant general, Knight of the Mannerheim Cross and a member of the Jäger movement. He participated in the Eastern Front of World War I, the Finnish Civil War, the Winter War and the Continuation War.

The VII Corps was a corps of the Finnish Army during the Continuation War of 1941 to 1944, where the Finnish Army fought alongside Germans against the Soviet Union. Under command of Major General Woldemar Hägglund, it took part in the Finnish invasions of Ladoga Karelia and East Karelia, including the capture of Petrozavodsk. During its existence, its composition varied significantly. It was disbanded in May 1943.