Seventeen days after the German invasion of Poland in 1939, which marked the beginning of the Second World War, the Soviet Union entered the eastern regions of Poland and annexed territories totalling 201,015 square kilometres (77,612 sq mi) with a population of 13,299,000. Inhabitants besides ethnic Poles included Belarusian and Ukrainian major population groups, and also Czechs, Lithuanians, Jews, and other minority groups.

Konstanty Plisowski of Odrowąż was a Polish general and military commander. He was the Commander in the battle of Jazłowiec and the battle of Brześć Litewski. He was murdered on Stalin's orders in the Katyn massacre.

Brigadier General Mieczysław Makary Smorawiński (1893–1940), was a Polish military commander and officer of the Polish Army. He was one of the Polish generals identified by forensic scientists of the Katyn Commission as the victim of the Soviet Katyn massacre of 1940.

Stanisław Swianiewicz was a Polish economist and historian. A veteran of the Polish-Soviet War, he was during World War II a survivor of the Katyn massacre and an eyewitness of the transport of Polish prisoners-of-war to the forests outside Smolensk by the NKVD.

Leon Billewicz was a Polish officer and a General of the Polish Army. He was murdered during the Katyń massacre.

Bronisław Bohatyrewicz of Ostoja was a Polish military commander and a general of the Polish Army. Murdered during the Katyn massacre, Bohatyrewicz was one of the Generals whose bodies were identified by forensic scientists of the Katyn Commission during the 1943 exhumation.

Alojzy Wir-Konas was a military commander in the Polish Army, commanding the 38th Infantry Division during the Invasion of Poland. He was murdered in the Katyn massacre.

Piotr Skuratowicz was a Polish military commander and a General of the Polish Army. A renowned cavalryman, he was arrested by the NKVD and murdered in the Katyn massacre.

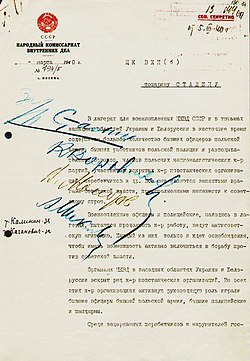

The Katyn massacre was a series of mass executions of nearly 22,000 Polish military officers and intelligentsia prisoners of war carried out by the Soviet Union, specifically the NKVD in April and May 1940. Though the killings also occurred in the Kalinin and Kharkiv prisons and elsewhere, the massacre is named after the Katyn forest, where some of the mass graves were first discovered by German Nazi forces.

Anders' Army was the informal yet common name of the Polish Armed Forces in the East in the 1941–42 period, in recognition of its commander Władysław Anders. The army was created in the Soviet Union but, in March 1942, based on an understanding between the British, Polish, and Soviets, it was evacuated from the Soviet Union and made its way through Iran to Palestine. There it passed under British command and provided the bulk of the units and troops of the Polish II Corps, which fought in the Italian Campaign. Anders' Army is notable for having been primarily composed of liberated POWs and for Wojtek, a bear who had honorary membership.

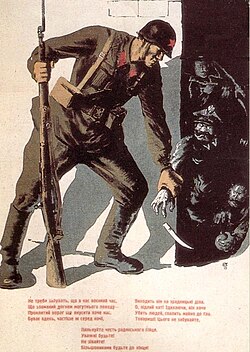

The Gestapo–NKVD conferences were a series of security police meetings organised in late 1939 and early 1940 by Germany and the Soviet Union, following the invasion of Poland in accordance with the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact. The meetings enabled both parties to pursue specific goals and aims as outlined independently by Hitler and Stalin, with regard to the acquired, formerly Polish territories. The conferences were held by the Gestapo and the NKVD officials in several Polish cities. In spite of their differences on other issues, both Heinrich Himmler and Lavrentiy Beria had similar objectives as far as the fate of pre-war Poland was concerned. The objectives were agreed upon during signing of the German–Soviet Boundary and Friendship Treaty on 28 September 1939.

Katyń is a 2007 Polish historical drama film about the 1940 Katyn massacre, directed by Academy Honorary Award winner Andrzej Wajda. It is based on the book Post Mortem: The Story of Katyn by Andrzej Mularczyk. It was nominated for Best Foreign Language Film for the 80th Academy Awards.

Zdzisław Peszkowski, of the Jastrzębiec coat of arms was a Polish Roman Catholic priest and one of a small group of Polish army officers who managed to survive the 1940 mass execution of 22,000 Polish citizens by NKVD, the Katyn massacre. Peszkowski was a leading advocate and chaplain for the Federation of Katyn Families, which works with survivors of the Katyn massacre and their families.

Leonard Wilhelm Skierski was a Polish military officer. He was a general of the Imperial Russian Army and then served in the Polish Army. He fought in World War I and in the Polish–Soviet War. He was one of fourteen Polish generals and one of the oldest military commanders to be murdered by the NKVD in the Katyn massacre of 1940.

Vasily Mikhailovich Blokhin was a Soviet secret police official who served as the chief executioner of the NKVD under the administrations of Genrikh Yagoda, Nikolay Yezhov, and Lavrentiy Beria.

Baruch or Boruch Steinberg was a Polish rabbi and military officer. He was Chief Rabbi of the Polish Army during the German invasion of Poland and Soviet invasion of Poland in 1939 and was executed by the Soviet Union in the Katyn massacre in April 1940.

Anti-Katyn is a denialism campaign intended to reduce and obscure the significance of the Katyn massacre of 1940 — where approximately 22,000 Polish officers were murdered by the Soviet NKVD on the orders of Joseph Stalin — by referencing the deaths from disease of thousands of Imperial Russian and Red Army soldiers at Polish internment camps during the Interwar period.

The Katyn Commission or the International Katyn Commission was a committee formed in April 1943 under request by Germany to investigate the Katyn massacre of some 22,000 Polish nationals during the Soviet occupation of Eastern Poland, mostly prisoners of war from the invasion of Poland including Polish Army officers, intelligentsia, civil servants, priests, police officers and numerous other professionals. Their bodies were discovered in a series of large mass graves in the forest near Smolensk in Russia following Operation Barbarossa.

Adam Solski was a soldier of the Polish Legions of World War I, a participant in the Polish–Soviet War, and a major in the Polish Army in the interwar period. Solski fought in the 1939 Invasion of Poland. Captured by the Red Army during the Soviet invasion of Poland, he was murdered in the Katyn massacre, on April 9, 1940.

The Select Committee to Conduct an Investigation and Study of the Facts, Evidence, and Circumstances of the Katyn Forest Massacre was established by United States House of Representatives in 1951, during the Korean War. At that time, there was concern that the Katyn Massacre could have served as a "blueprint" for the execution of U.S. troops by Communist forces.