Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) is a viral respiratory disease of zoonotic origin caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus, the first identified strain of the SARS coronavirus species, severe acute respiratory syndrome–related coronavirus (SARSr-CoV). The first known cases occurred in November 2002, and the syndrome caused the 2002–2004 SARS outbreak. In the 2010s, Chinese scientists traced the virus through the intermediary of Asian palm civets to cave-dwelling horseshoe bats in Xiyang Yi Ethnic Township, Yunnan.

Coronaviruses are a group of related RNA viruses that cause diseases in mammals and birds. In humans and birds, they cause respiratory tract infections that can range from mild to lethal. Mild illnesses in humans include some cases of the common cold, while more lethal varieties can cause SARS, MERS and COVID-19, which is causing the ongoing pandemic. In cows and pigs they cause diarrhea, while in mice they cause hepatitis and encephalomyelitis.

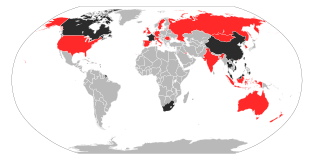

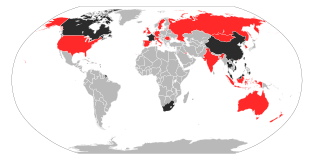

The 2002–2004 outbreak of SARS, caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus, infected over 8,000 people from 29 countries and territories, and resulted in at least 774 deaths worldwide.

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 1 is a strain of coronavirus that causes severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), the respiratory illness responsible for the 2002–2004 SARS outbreak. It is an enveloped, positive-sense, single-stranded RNA virus that infects the epithelial cells within the lungs. The virus enters the host cell by binding to angiotensin-converting enzyme 2. It infects humans, bats, and palm civets.

Human coronavirus NL63 (HCoV-NL63) is a species of coronavirus, specifically a Setracovirus from among the Alphacoronavirus genus. It was identified in late 2004 in patients in the Netherlands. The virus is an enveloped, positive-sense, single-stranded RNA virus which enters its host cell by binding to ACE2. Infection with the virus has been confirmed worldwide, and has an association with many common symptoms and diseases. Associated diseases include mild to moderate upper respiratory tract infections, severe lower respiratory tract infection, croup and bronchiolitis.

Walter Ian Lipkin is the John Snow Professor of Epidemiology at the Mailman School of Public Health at Columbia University and a professor of Neurology and Pathology at the College of Physicians and Surgeons at Columbia University. He is also director of the Center for Infection and Immunity, an academic laboratory for microbe hunting in acute and chronic diseases. Lipkin is internationally recognized for his work with West Nile virus, SARS and COVID-19.

Middle East respiratory syndrome–related coronavirus (MERS-CoV), or EMC/2012 (HCoV-EMC/2012), is the virus that causes Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS). It is a species of coronavirus which infects humans, bats, and camels. The infecting virus is an enveloped, positive-sense, single-stranded RNA virus which enters its host cell by binding to the DPP4 receptor. The species is a member of the genus Betacoronavirus and subgenus Merbecovirus.

Novel coronavirus (nCoV) is a provisional name given to coronaviruses of medical significance before a permanent name is decided upon. Although coronaviruses are endemic in humans and infections normally mild, such as the common cold, cross-species transmission has produced some unusually virulent strains which can cause viral pneumonia and in serious cases even acute respiratory distress syndrome and death.

Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) is a viral respiratory infection caused by Middle East respiratory syndrome–related coronavirus (MERS-CoV). Symptoms may range from none, to mild, to severe. Typical symptoms include fever, cough, diarrhea, and shortness of breath. The disease is typically more severe in those with other health problems.

Human coronavirus 229E (HCoV-229E) is a species of coronavirus which infects humans and bats. It is an enveloped, positive-sense, single-stranded RNA virus which enters its host cell by binding to the APN receptor. Along with Human coronavirus OC43, it is one of the viruses responsible for the common cold. HCoV-229E is a member of the genus Alphacoronavirus and subgenus Duvinacovirus.

MERS coronavirus EMC/2012 is a strain of coronavirus isolated from the sputum of the first person to become infected with what was later named Middle East respiratory syndrome–related coronavirus (MERS-CoV), a virus that causes Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS).

London1_novel CoV/2012 is a coronavirus strain isolated from a Qatari man in London in 2012 who was one of the first patients to come down with what has since been named Middle East respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus (MERS-CoV). The Qatari patient had traveled to Saudi Arabia from Qatar. He returned to Qatar, but when he fell ill, he traveled to London for treatment. The United Kingdom's Health Protection Agency (HPA) named the virus.

An outbreak of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus occurred in South Korea from May 2015 to July 2015. The virus, which causes Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS), was a newly emerged betacoronavirus that was first identified in a patient from Saudi Arabia in April 2012. From the outbreak, a total of 186 cases were infected in the country, with a death toll of 38.

The 2018 Middle East respiratory syndrome outbreak was a set of infections of Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS-CoV). The cases were most numerous in, and are believed to have originated from, Saudi Arabia.

The COVID-19 pandemic in Egypt is part of the worldwide pandemic of coronavirus disease 2019 caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2. The virus was confirmed to have reached Egypt on 14 February 2020.

COVID-19 surveillance involves monitoring the spread of the coronavirus disease in order to establish the patterns of disease progression. The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends active surveillance, with focus of case finding, testing and contact tracing in all transmission scenarios. COVID-19 surveillance is expected to monitor epidemiological trends, rapidly detect new cases, and based on this information, provide epidemiological information to conduct risk assessment and guide disease preparedness.

Allison Joan McGeer is a Canadian infectious disease specialist in the Sinai Health System, and a professor in the Department of Laboratory Medicine and Pathobiology at the University of Toronto. She also appointed at the Dalla Lana School of Public Health and a Senior Clinician Scientist at the Lunenfeld-Tanenbaum Research Institute, and is a partner of the National Collaborating Centre for Infectious Diseases. McGeer has led investigations into the severe acute respiratory syndrome outbreak in Toronto and worked alongside Donald Low. During the COVID-19 pandemic, McGeer has studied how SARS-CoV-2 survives in the air and has served on several provincial committees advising aspects of the Government of Ontario's pandemic response.

The COVID-19 pandemic in the Bicol Region is part of the worldwide pandemic of coronavirus disease 2019 caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2. The virus reached the Bicol Region on March 27, 2020, when the first case of the disease was confirmed in Albay.

Overseas Filipinos, including Filipino migrant workers outside the Philippines, have been affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. As of June 1, 2021, there have been 19,765 confirmed COVID-19 cases of Filipino citizens residing outside the Philippines with 12,037 recoveries and 1,194 deaths. The official count from the Department of Foreign Affairs (DFA) on the cases of overseas Filipinos is not included in the national tally of the Philippine government. Repatriates on the other hand are included in the national tally of the Department of Health (DOH) but are listed separately from regional counts.

The history of coronaviruses is an account of the discovery of the diseases caused by coronaviruses and the diseases they cause. It starts with the first report of a new type of upper-respiratory tract disease among chickens in North Dakota, U.S., in 1931. The causative agent was identified as a virus in 1933. By 1936, the disease and the virus were recognised as unique from other viral disease. They became known as infectious bronchitis virus (IBV), but later officially renamed as Avian coronavirus.