The Champ de Mars Massacre took place on 17 July 1791 in Paris against a crowd of republican protesters in the midst of the French Revolution. The event is named after the site of the massacre, the Champ de Mars. Two days before, the National Constituent Assembly issued a decree that the king, Louis XVI, would retain his throne under a constitutional monarchy. This decision came after Louis and his family had unsuccessfully tried to flee France in the Flight to Varennes the month before. Later that day, leaders of the republicans in France rallied against this decision, eventually leading royalist Lafayette to order the massacre. [1]

Paris is the capital and most populous city of France, with an area of 105 square kilometres and an official estimated population of 2,140,526 residents as of 1 January 2019. Since the 17th century, Paris has been one of Europe's major centres of finance, commerce, fashion, science, and the arts.

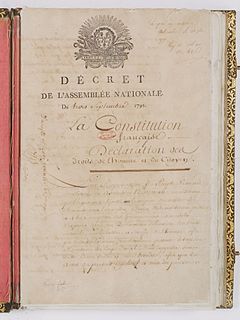

The French Revolution was a period of far-reaching social and political upheaval in France and its colonies beginning in 1789. The Revolution overthrew the monarchy, established a republic, catalyzed violent periods of political turmoil, and finally culminated in a dictatorship under Napoleon who brought many of its principles to areas he conquered in Western Europe and beyond. Inspired by liberal and radical ideas, the Revolution profoundly altered the course of modern history, triggering the global decline of absolute monarchies while replacing them with republics and liberal democracies. Through the Revolutionary Wars, it unleashed a wave of global conflicts that extended from the Caribbean to the Middle East. Historians widely regard the Revolution as one of the most important events in human history.

The Champ de Mars is a large public greenspace in Paris, France, located in the seventh arrondissement, between the Eiffel Tower to the northwest and the École Militaire to the southeast. The park is named after the Campus Martius in Rome, a tribute to the Latin name of the Roman God of war. The name also alludes to the fact that the lawns here were formerly used as drilling and marching grounds by the French military.

Contents

Jacques Pierre Brissot, editor and main writer of Le Patriote français and president of the Comité des Recherches of Paris, drew up a petition demanding the removal of the king. A crowd of 50,000 people gathered at the Champ de Mars on July 17 to sign the petition, [2] with about 6,000 having signed the petition. However, earlier that day two suspicious people had been found hiding at the Champ de Mars, "possibly with the intention of getting a better view of the ladies' ankles", and were hanged by those who found them. Jean Sylvain Bailly, the mayor of Paris, used this incident to declare martial law. [3] The Marquis de Lafayette and the National Guard, which was under his command, were able to disperse the crowd.

Jacques Pierre Brissot, who assumed the name of de Warville, was a leading member of the Girondins during the French Revolution and founder of the abolitionist Society of the Friends of the Blacks. Some sources give his name as Jean Pierre Brissot.

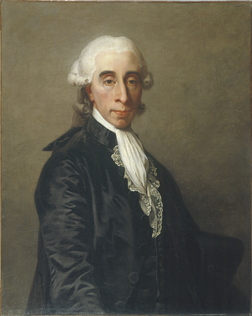

Jean Sylvain Bailly was a French astronomer, mathematician, freemason, and political leader of the early part of the French Revolution. He presided over the Tennis Court Oath, served as the mayor of Paris from 1789 to 1791, and was ultimately guillotined during the Reign of Terror.

Marie-Joseph Paul Yves Roch Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de Lafayette, known in the United States simply as Lafayette, was a French aristocrat and military officer who fought in the American Revolutionary War, commanding American troops in several battles, including the Siege of Yorktown. After returning to France, he was a key figure in the French Revolution of 1789 and the July Revolution of 1830.

Later in the afternoon, the crowd, led by Danton and Camille Desmoulins, returned in even greater numbers. The larger crowd was also more determined than the first. Lafayette again tried to disperse it. In retaliation, the crowd threw stones at the National Guard. After firing unsuccessful warning shots, the National Guard opened fire directly on the crowd. The exact numbers of dead and wounded are unknown; estimates range from a dozen to fifty dead. [2]

Georges Jacques Danton was a leading figure in the early stages of the French Revolution, in particular as the first president of the Committee of Public Safety. Danton's role in the onset of the Revolution has been disputed; many historians describe him as "the chief force in the overthrow of the French monarchy and the establishment of the First French Republic".

Lucie-Simplice-Camille-Benoît Desmoulins was a journalist and politician who played an important role in the French Revolution. He was a schoolmate of Maximilien Robespierre and a close friend and political ally of Georges Danton, who were influential figures in the French Revolution. Desmoulins was tried and executed alongside Danton when the Committee of Public Safety reacted against Dantonist opposition.