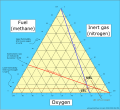

Flammability diagrams show the control of flammability in mixtures of fuel, oxygen and an inert gas, typically nitrogen. Mixtures of the three gasses are usually depicted in a triangular diagram, known as a ternary plot. Such diagrams are available in literature. [1] [2] [3] [4] . The same information can be depicted in a normal orthogonal diagram, showing only two substances, implicitly using the feature that the sum of all three components is 100 percent. The diagrams below only concerns one fuel; the diagrams can be generalized to mixtures of fuels.