Silesia is a historical region of Central Europe that lies mostly within Poland, with small parts in the Czech Republic and Germany. Its area is approximately 40,000 km2 (15,400 sq mi), and the population is estimated at 8,000,000. Silesia is split into two main subregions, Lower Silesia in the west and Upper Silesia in the east. Silesia has a diverse culture, including architecture, costumes, cuisine, traditions, and the Silesian language. The largest city of the region is Wrocław.

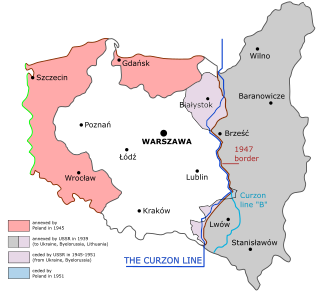

During the later stages of World War II and the post-war period, Germans and Volksdeutsche fled and were expelled from various Eastern and Central European countries, including Czechoslovakia, and from the former German provinces of Lower and Upper Silesia, East Prussia, and the eastern parts of Brandenburg (Neumark) and Pomerania (Hinterpommern), which were annexed by Poland and the Soviet Union.

Opole is a city located in southern Poland on the Oder River and the historical capital of Upper Silesia. With a population of approximately 127,387 as of the 2021 census, it is the capital of Opole Voivodeship (province) and the seat of Opole County. Its built-up was home to 146,522 inhabitants. It is the largest city in its province.

Upper Silesia is the southeastern part of the historical and geographical region of Silesia, located today mostly in Poland, with small parts in the Czech Republic. The area is predominantly known for its heavy industry.

Silesian, Silesian German or Lower Silesian is a nearly extinct German dialect spoken in Silesia. It is part of the East Central German language area with some West Slavic and Lechitic influences. Silesian German emerged as the result of Late Medieval German migration to Silesia, which had been inhabited by Lechitic or West Slavic peoples in the Early Middle Ages.

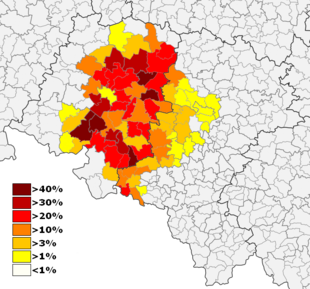

The Upper Silesia plebiscite was a plebiscite mandated by the Versailles Treaty and carried out on 20 March 1921 to determine ownership of the province of Upper Silesia between Weimar Germany and Poland. The region was ethnically mixed with both Germans and Poles; according to prewar statistics, ethnic Poles formed 60 percent of the population. Under the previous rule by the German Empire, Poles claimed they had faced discrimination, making them effectively second class citizens. The period of the plebiscite campaign and inter-Allied occupation was marked by violence. There were three Polish uprisings, and German volunteer paramilitary units came to the region as well.

Trans-Olza, also known as Trans-Olza Silesia, is a territory in the Czech Republic, which was disputed between Poland and Czechoslovakia during the Interwar Period. Its name comes from the Olza River.

Silesians is a geographical term for the inhabitants of Silesia, a historical region in Central Europe divided by the current national boundaries of Poland, Germany, and the Czech Republic. Historically, the region of Silesia has been inhabited by Polish, Czechs, and by Germans. Therefore, the term Silesian can refer to anyone of these ethnic groups. However, in 1945, great demographic changes occurred in the region as a result of the Potsdam Agreement leaving most of the region ethnically Polish and/or Slavic Upper Silesian. The Silesian dialect is one of the main dialects of the Polish language and based on Polish/Lechitic grammar. The names of Silesia in different languages most likely share their etymology—Polish: ; German: Schlesienpronounced[ˈʃleːzi̯ən] ; Czech: Slezsko ; Lower Silesian: Schläsing; Silesian: Ślōnsk ; Lower Sorbian: Šlazyńska ; Upper Sorbian: Šleska ; Latin, Spanish and English: Silesia; French: Silésie; Dutch: Silezië; Italian: Slesia; Slovak: Sliezsko; Kashubian: Sląsk. The names all relate to the name of a river and mountain in mid-southern Silesia, which served as a place of cult for pagans before Christianization.

The Province of Upper Silesia was a province of the Free State of Prussia from 1919 to 1945. It comprised much of the region of Upper Silesia and was eventually divided into two government regions called Kattowitz (1939–1945), and Oppeln (1819–1945). The provincial capital was Oppeln (1919–1938) and Kattowitz (1941–1945), while other major towns included Beuthen, Gleiwitz, Hindenburg O.S., Neiße, Ratibor and Auschwitz, added in 1941. Between 1938 and 1941 it was reunited with Lower Silesia as the Province of Silesia.

Union of Poles in Germany is an organisation of the Polish minority in Germany, founded in 1922. In 1924, the union initiated collaboration between other minorities, including Sorbs, Danes, Frisians and Lithuanians, under the umbrella organization Association of National Minorities in Germany. From 1939 until 1945 the Union was outlawed in Nazi Germany. After 1945 it had lost some of its influence; in 1950 the Union of Poles in Germany split into two organizations: the Union of Poles in Germany, which refused to recognize the communist Polish government of the Polish United Workers' Party, and the Union of Poles "Zgoda" (Unity), which recognized the new communist government in Warsaw and had contacts with it. The split was healed in 1991. The organization is a memebr of the Federal Union of European Nationalities.

Poles in Germany are the second largest Polish diaspora (Polonia) in the world and the biggest in Europe. Estimates of the number of Poles living in Germany vary from 2 million to about 3 million people living that might be of Polish descent. Their number has quickly decreased over the years, and according to the latest census, there are approximately 866,690 Poles in Germany. The main Polonia organisations in Germany are the Union of Poles in Germany and Congress of Polonia in Germany. Polish surnames are relatively common in Germany, especially in the Ruhr area.

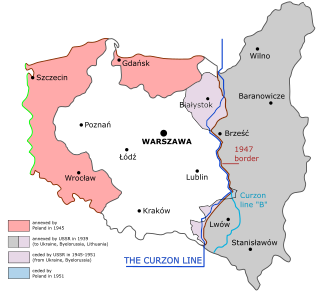

The flight and expulsion of Germans from Poland was the largest of a series of flights and expulsions of Germans in Europe during and after World War II. The German population fled or was expelled from all regions which are currently within the territorial boundaries of Poland: including the former eastern territories of Germany annexed by Poland after the war and parts of pre-war Poland; despite acquiring territories from Germany, the Poles themselves were also expelled from the former eastern territories of Poland annexed by the Soviet Union. West German government figures of those evacuated, migrated, or expelled by 1950 totaled 8,030,000. Research by the West German government put the figure of Germans emigrating from Poland from 1951 to 1982 at 894,000; they are also considered expellees under German Federal Expellee Law.

As a result of World War II, Poland's borders were shifted west. Within Poland's new boundaries there remained a substantial number of ethnic Germans, who were expelled from Poland until 1951. The remaining former German citizens were primarily autochthons, who were allowed to stay in post-war Poland after declaring Polish nationality in a verification process. According to article 116 of the German constitution, all former German citizens may be "re-granted German citizenship on application" and are "considered as not having been deprived of their German citizenship if they have established their domicile in Germany after May 8, 1945 and have not expressed a contrary intention." This regulation allowed the autochthons, and ethnic Germans permitted to stay in Poland, to reclaim German citizenship and settle in West Germany. In addition to those groups, a substantial number of Poles who never had German citizenship were emigrating to West Germany during the period of the People's Republic of Poland for political and economic reasons.

The Deutsche Volksliste, a Nazi Party institution, aimed to classify inhabitants of Nazi-occupied territories (1939–1945) into categories of desirability according to criteria systematised by Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler. The institution originated in occupied western Poland. Similar schemes were subsequently developed in Occupied France (1940–1944) and in the Reichskommissariat Ukraine (1941–1944).

The German evacuation from Central and Eastern Europe ahead of the Soviet Red Army advance during the Second World War was delayed until the last moment. Plans to evacuate people to present-day Germany from the territories controlled by Nazi Germany in Central and Eastern Europe, including from the former eastern territories of Germany as well as occupied territories, were prepared by the German authorities only when the defeat was inevitable, which resulted in utter chaos. The evacuation in most of the Nazi-occupied areas began in January 1945, when the Red Army was already rapidly advancing westward.

After centuries of relative ethnic diversity, the population of modern Poland has become nearly completely ethnically homogeneous Polish as a result of altered borders and the Nazi German and Soviet or Polish Communist campaigns of genocide, expulsion and deportation during and after World War II. Ethnic minorities remain in Poland, however, including some newly arrived or increased in number. Ethnic groups include Germans, Ukrainians and Belarusians.

The bilateral relations between Poland and Germany have been marked by an extensive and complicated history.

The Recovered Territories or Regained Lands, also known as the Western Borderlands, and previously as the Western and Northern Territories, Postulated Territories and Returning Territories, are the former eastern territories of Germany and the Free City of Danzig that became part of Poland after World War II, at which time most of their German inhabitants were forcibly deported.

The Commission for the Determination of Place Names was a commission of the Polish Department of Public Administration, founded in January 1946. Its mission was the establishment of toponyms for places, villages, towns and cities in the former eastern territories of Germany.

The Expulsion of Poles by Nazi Germany during World War II was a massive operation consisting of the forced resettlement of over 1.7 million Poles from the territories of German-occupied Poland, with the aim of their Germanization between 1939 and 1944.