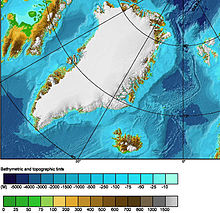

Jan Mayen is a Norwegian volcanic island in the Arctic Ocean with no permanent population. It is 55 km (34 mi) long (southwest-northeast) and 373 km2 (144 sq mi) in area, partly covered by glaciers. It has two parts: larger northeast Nord-Jan and smaller Sør-Jan, linked by a 2.5 km (1.6 mi) wide isthmus. It lies 600 km (370 mi) northeast of Iceland, 500 km (310 mi) east of central Greenland, and 900 km (560 mi) northwest of Vesterålen, Norway. The island is mountainous, the highest summit being the Beerenberg volcano in the north. The isthmus is the location of the two largest lakes of the island, Sørlaguna and Nordlaguna. A third lake is called Ullerenglaguna. Jan Mayen was formed by the Jan Mayen hotspot and is defined by geologists as a microcontinent.

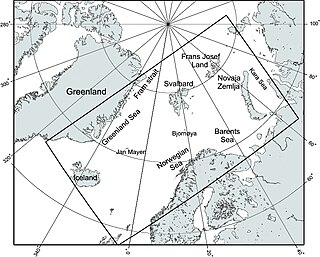

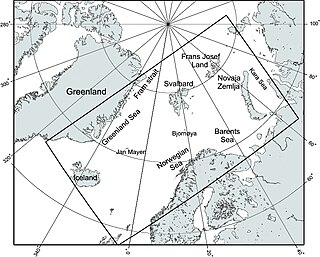

The Norwegian Sea is a marginal sea, grouped with either the Atlantic Ocean or the Arctic Ocean, northwest of Norway between the North Sea and the Greenland Sea, adjoining the Barents Sea to the northeast. In the southwest, it is separated from the Atlantic Ocean by a submarine ridge running between Iceland and the Faroe Islands. To the north, the Jan Mayen Ridge separates it from the Greenland Sea.

Svalbard, previously known as Spitsbergen or Spitzbergen, is a Norwegian archipelago in the Arctic Ocean. North of mainland Europe, it lies about midway between the northern coast of Norway and the North Pole. The islands of the group range from 74° to 81° north latitude, and from 10° to 35° east longitude. The largest island is Spitsbergen, followed in size by Nordaustlandet and Edgeøya. The largest settlement is Longyearbyen on the west coast of Spitsbergen.

Spitsbergen, is the largest and the only permanently populated island of the Svalbard archipelago in northern Norway.

Bear Island is the southernmost island of the Norwegian Svalbard archipelago. The island is located at the limits of the Norwegian and Barents Seas, approximately halfway between Spitsbergen and the North Cape. Bear Island was discovered by Dutch explorers Willem Barentsz and Jacob van Heemskerck on 10 June 1596. It was named after a polar bear that was seen swimming nearby. The island was considered terra nullius until the Spitsbergen Treaty of 1920 placed it under Norwegian sovereignty.

Svalbard and Jan Mayen is a statistical designation defined by ISO 3166-1 for a collective grouping of two remote jurisdictions of Norway: Svalbard and Jan Mayen. While the two are combined for the purposes of the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) category, they are not administratively related. This has further resulted in the country code top-level domain .sj being issued for Svalbard and Jan Mayen, and ISO 3166-2:SJ. The United Nations Statistics Division also uses this code, but has named it the Svalbard and Jan Mayen Islands.

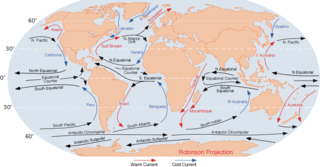

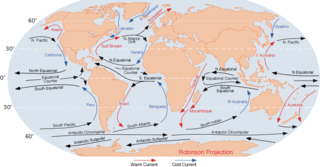

An ocean current is a continuous, directed movement of seawater generated by a number of forces acting upon the water, including wind, the Coriolis effect, breaking waves, cabbeling, and temperature and salinity differences. Depth contours, shoreline configurations, and interactions with other currents influence a current's direction and strength. Ocean currents are primarily horizontal water movements.

Baffin Bay, located between Baffin Island and the west coast of Greenland, is defined by the International Hydrographic Organization as a marginal sea of the Arctic Ocean. It is sometimes considered a sea of the North Atlantic Ocean. It is connected to the Atlantic via Davis Strait and the Labrador Sea. The narrower Nares Strait connects Baffin Bay with the Arctic Ocean. The bay is not navigable most of the year because of the ice cover and high density of floating ice and icebergs in the open areas. However, a polynya of about 80,000 km2 (31,000 sq mi), known as the North Water, opens in summer on the north near Smith Sound. Most of the aquatic life of the bay is concentrated near that region.

The East Greenland Current (EGC) is a cold, low-salinity current that extends from Fram Strait (~80N) to Cape Farewell (~60N). The current is located off the eastern coast of Greenland along the Greenland continental margin. The current cuts through the Nordic Seas and through the Denmark Strait. The current is of major importance because it directly connects the Arctic to the Northern Atlantic, it is a major contributor to sea ice export out of the Arctic, and it is a major freshwater sink for the Arctic.

The Norwegian Polar Institute is Norway's central governmental institution for scientific research, mapping and environmental monitoring in the Arctic and the Antarctic. The NPI is a directorate under Norway's Ministry of Climate and Environment. The institute advises Norwegian authorities on matters concerning polar environmental management and is the official environmental management body for Norwegian activities in Antarctica.

The West Ice is a patch of the Greenland Sea covered by pack ice during winter time. It is located north of Iceland, between East Greenland and Jan Mayen island. In Greenland and the Danish language, vestisen refers to the sea ice-covered waters off Greenland's west coast.

The Arctic Ocean is the smallest and shallowest of the world's five major oceans. It spans an area of approximately 14,060,000 km2 (5,430,000 sq mi) and is known as one of the coldest of oceans. The International Hydrographic Organization (IHO) recognizes it as an ocean, although some oceanographers call it the Arctic Mediterranean Sea. It has also been described as an estuary of the Atlantic Ocean. It is also seen as the northernmost part of the all-encompassing World Ocean.

Svalbard is a Norwegian archipelago in the Arctic Ocean. The climate of Svalbard is principally a result of its latitude, which is between 74° and 81° north. Climate is defined by the World Meteorological Organization as the average weather over a 30-year period. The North Atlantic Current moderates Svalbard's temperatures, particularly during winter, giving it up to 20 °C (36 °F) higher winter temperature than similar latitudes in continental Russia and Canada. This keeps the surrounding waters open and navigable most of the year. The interior fjord areas and valleys, sheltered by the mountains, have fewer temperature differences than the coast, with about 2 °C lower summer temperatures and 3 °C higher winter temperatures. On the south of the largest island, Spitsbergen, the temperature is slightly higher than further north and west. During winter, the temperature difference between south and north is typically 5 °C, and about 3 °C in summer. Bear Island (Bjørnøya) has average temperatures even higher than the rest of the archipelago.

The Fram Strait is the passage between Greenland and Svalbard, located roughly between 77°N and 81°N latitudes and centered on the prime meridian. The Greenland and Norwegian Seas lie south of Fram Strait, while the Nansen Basin of the Arctic Ocean lies to the north. Fram Strait is noted for being the only deep connection between the Arctic Ocean and the World Oceans. The dominant oceanographic features of the region are the West Spitsbergen Current on the east side of the strait and the East Greenland Current on the west.

The bowhead whale is a species of baleen whale belonging to the family Balaenidae and is the only living representative of the genus Balaena. It is the only baleen whale endemic to the Arctic and subarctic waters, and is named after its characteristic massive triangular skull, which it uses to break through Arctic ice. Other common names of the species included the Greenland right whale, Arctic whale, steeple-top, and polar whale.

Operation Fritham was an Allied military operation during the Second World War to secure the coal mines on Spitsbergen, the main island of the Svalbard Archipelago, 650 mi (1,050 km) from the North Pole and about the same distance from Norway. The operation was intended to deny the islands to Nazi Germany.

The West Spitsbergen Current (WSC) is a warm, salty current that runs poleward just west of Spitsbergen,, in the Arctic Ocean. The WSC branches off the Norwegian Atlantic Current in the Norwegian Sea. The WSC is of importance because it drives warm and salty Atlantic Water into the interior Arctic. The warm and salty WSC flows north through the eastern side of Fram Strait, while the East Greenland Current (EGC) flows south through the western side of Fram Strait. The EGC is characterized by being very cold and low in salinity, but above all else it is a major exporter of Arctic sea ice. Thus, the EGC combined with the warm WSC makes the Fram Strait the northernmost ocean area having ice-free conditions throughout the year in all of the global ocean.

The Nordic Seas are located north of Iceland and south of Svalbard. They have also been defined as the region located north of the Greenland-Scotland Ridge and south of the Fram Strait-Spitsbergen-Norway intersection. Known to connect the North Pacific and the North Atlantic waters, this region is also known as having some of the densest waters, creating the densest region found in the North Atlantic Deep Water. The deepest waters of the Arctic Ocean are connected to the worlds other oceans through Nordic Seas and Fram Strait. There are three seas within the Nordic Sea: Greenland Sea, Norwegian Sea, and Iceland Sea. The Nordic Seas only make up about 0.75% of the World's Oceans. This region is known as having diverse features in such a small topographic area, such as the mid oceanic ridge systems. Some locations have shallow shelves, while others have deep slopes and basins. This region, because of the atmosphere-ocean transfer of energy and gases, has varying seasonal climate. During the winter, sea ice is formed in the western and northern regions of the Nordic Seas, whereas during the summer months, the majority of the region remains free of ice.

Operation Gearbox was a joint Norwegian and British operation to occupy the Arctic island of Spitsbergen during the Second World War. It superseded Operation Fritham, an expedition in May, to secure the coal mines on Spitsbergen, the main island of the Svalbard Archipelago which had failed when attacked by four German Focke-Wulf Fw 200 Condor reconnaissance bombers. The Norwegian force, with 116 long tons (118 t) of supplies, arrived by British cruiser on 2 July.